Oli Genn-Bash (Brighton, UK) joins Joe Moore for a grounded conversation on the boom in functional mushrooms and why the category may be moving too quickly. As the founder of The Fungi Consultant, Oli works with consumers and brands to demystify functional mushrooms, with a focus on education, traceability, and realistic expectations.

The conversation begins with a critique of wellness hype cycles. Oli explains how consumer desperation for help with anxiety, sleep, stress, and cognition can create an opening for a rapid wave of products that are not always grounded in careful sourcing or clear science. Using lion’s mane as a case study, he contrasts popular cognitive claims with traditional use, arguing that the most useful path forward is to slow down, get more literate about mechanisms, and build a market that can sustain trust over time.

Systems and Culture

Oli describes how individual health is inseparable from community realities, including food access, class dynamics, and what wellness advice can sound like when it lands from a place of privilege. They discuss mycelial thinking as a practical framework for collaboration and resource-sharing, and why mushrooms tend to attract unusually generous “teach everyone” communities.

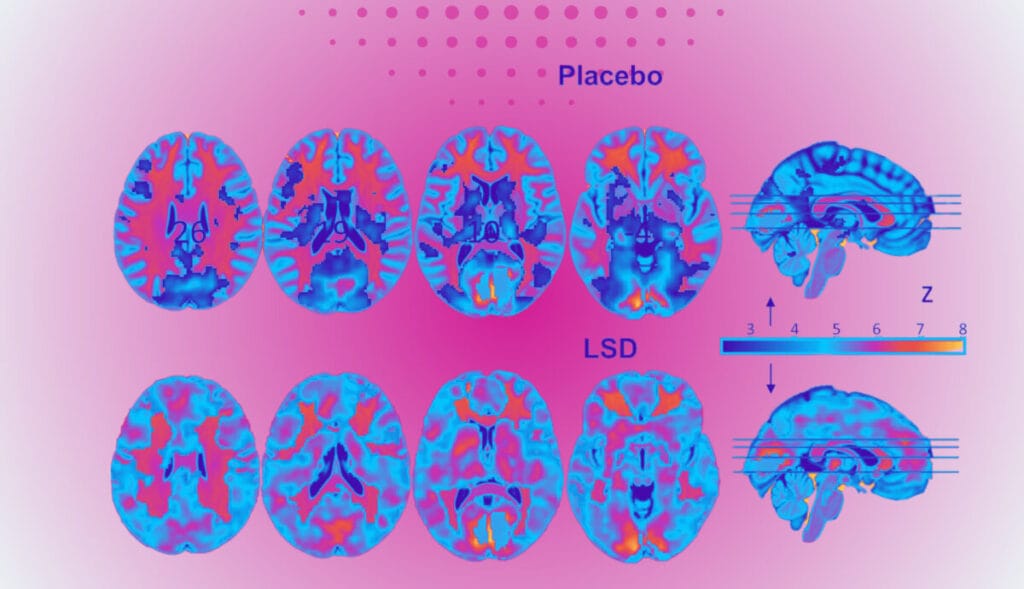

They also explore the role of mushrooms in meaning-making and consciousness. Oli shares personal reflections on mushrooms as allies, the felt sense of “agency” in psychedelic experiences, and how those experiences can encourage behavioral change without forcing it. The conversation touches on alcohol culture in the UK and the possibility of non-alcoholic alternatives, including how functional mushrooms, microdosing, and other botanicals can support social confidence and energy for some people.

Finally, they look ahead at fungal innovation beyond supplements: materials, soil health, regenerative approaches, bioremediation, and what the broader psychedelic movement might learn from fungi’s patience, symbiosis, and balance.

Key themes and takeaways

1) Why functional mushrooms feel “too fast” right now

Oli argues that functional mushrooms have accelerated into a high-pressure wellness marketplace, with brands rushing products to market and consumers struggling to determine what is legitimate, traceable, and effective. He draws parallels to the UK CBD market, describing how oversaturation and inconsistent quality can erode trust and collapse prices.

2) Lion’s mane, tradition, and mechanism

Lion’s mane is a useful example of how modern marketing can outrun nuance. Oli notes the gap between popular cognitive claims and traditional use, and points toward the gut-brain axis as one plausible bridge that requires more careful explanation and patience.

3) “Functional mushrooms” as a frame

Oli prefers the term functional mushrooms over medicinal mushrooms, emphasizing systems-level support rather than a pharmaceutical model. He describes a view of health that starts on the cellular level and asks what supports function, resilience, and prevention.

4) Health is individual and collective

Oli speaks candidly about barriers to wellness in the UK, including food poverty, access to education about cooking, and how class dynamics shape what health messaging sounds like. The broader point is structural: it is difficult to talk about supplements without considering the baseline conditions of daily life.

5) Mycelial thinking, futures work, and collaboration

The conversation highlights “mycelial thinking” as more than a metaphor. Oli describes collaborations in futures-oriented communities and how fungal logic can inform collaboration, non-zero-sum outcomes, and resource sharing.

6) Mushroom culture and the instinct to share

Joe notes how strikingly generous mushroom communities can be, especially around cultivation and identification. Oli agrees and adds a provocative angle: the possibility of “agency” in fungi and a sense that mushrooms invite humans into relationship, curiosity, and participation.

7) Alcohol culture and alternatives

Oli reflects on nearly three years without alcohol and describes how functional mushrooms and other botanicals can support mood, energy, and social confidence for some people. They also discuss the realities of events culture, including the need for more inclusive non-alcoholic options and sensitivity to addiction histories.

8) The next 10 years of fungi

They look at the expansion of fungi into materials, fashion, regenerative agriculture, soil health, and bioremediation. Oli emphasizes balance: fungal innovations are promising, but scaling and real-world constraints matter.

9) What the psychedelic movement can learn from fungi

Oli critiques extractive, capital-driven dynamics in the psychedelic ecosystem and suggests fungi offer a different ethic: patience, humility, symbiosis, and realism about parasitism and imbalance.

Transcript

Joe Moore: [00:00:00] All right. Psychedelics today is back in live. Oli, how are you doing today?

Oli Genn-Bash: Good. How are you doing, Joe?

Joe Moore: Doing great. Happy to be here with you to talk about mushrooms and a lot more. Um, yes. Yeah. And you’re joining us today from Brighton, uk, is that right?

Oli Genn-Bash: That’s right down on the south coast,

Joe Moore: yeah.

Joe Moore: Awesome. Um, so we got connected through our friends over at Phil Delic and, uh, they’re coming up this weekend. So shout out to Phil Delic. Thanks for connecting us. And, um, so you, you kind of run an organization called the Fungi Consultant. I assume you’re doing a lot, a lot of kind of helping people kind of understand and connect to mushroom culture.

Joe Moore: Is that right?

Oli Genn-Bash: Yeah, so I guess demystifying functional mushrooms primarily because they’ve become. Quite a hyped up [00:01:00] wellness product. They seem to have exploded in recent months. Recent years, and I think things have maybe moved too quickly. So I do educational sessions, give talks, one-to-one consultations, as well as, uh, consulting with different brands who are looking to develop products and just learn more about the space, people that are coming from different areas in the wellness industry that want to start utilizing the benefits of functional mushrooms.

Joe Moore: Yeah, great. There’s, there’s so much there. And I think like, oh gosh. Yeah, I don’t know. Is, is it too fast or too slow or too late is the right framing, right? It’s, it’s hard because we’ve come from such a micropho place and we’re looking towards micro fillic cultures like Japan, and [00:02:00] we’re just like, what do we do here?

Oli Genn-Bash: There’s, I think, a sentiment at the moment where, and this relates to psychedelics and we can talk about this as well, where people are feeling like they’re in a situation which is quite desperate. So the narrative with all things wellness is, okay, you have something going on. Okay. We’ve been able to identify quite core issues when it comes to functional mushrooms, things like anxiety, sleep stress, cognitive function.

Oli Genn-Bash: These are all key things that we need to focus on. So when we see something that could provide that lifeline. We go, okay, brilliant. And then everyone starts talking about Lion’s name, for example, as benefit for cognitive function. But actually if you look at the traditional use of it, it’s been, um, recommended for [00:03:00] digestive issues and the gut.

Oli Genn-Bash: Okay. So does that mean we need to then look at what’s going on in the gut microbiome and the gut brain axis and, okay, how’s that having an indirect effect? So maybe we need to slow down and really think about what’s going on and tease things apart. I do find that there’s not necessarily that same patience that I have.

Oli Genn-Bash: I really like to nerd out with it. So I like to understand what’s going on, and I understand it from the consumer point of view where they want something that’s just going to help them. But in doing that, it’s like. There’s a weird, I dunno, you could call it the capitalist machine or something. This, this creature that sees an opportunity and goes, okay, brilliant.

Oli Genn-Bash: And then it spurts out all of these brands and people are just slapping their logo on a product. They’re having a contract manufacturer make it. They’re not, they necessarily involved in the traceability or all the [00:04:00] steps involved. And then we just start to see an explosion like any other industry. So my concern is that it could end up collapsing.

Oli Genn-Bash: So, you know, I’ve seen it happen with the CBD industry in the UK where there’s just so many brands and then the price of CBD collapsed and then it wasn’t really viable. There was too much CBD being produced and people kind of lost faith in it because. There’s just, you know, you try one thing and it’s not good.

Oli Genn-Bash: You try another thing and it’s not good. And after a while you just go, okay, well how do I actually know which product works for me? And because we can’t, the industry is tied by the fact that it can’t recommend these products for medicinal use. So then my take is that if we slow down, if we educate ourselves, if we can be comfortable with nerding out a bit, [00:05:00] then we’ll be able to strengthen the industry.

Joe Moore: Hmm. So

Joe Moore: capitalism always requires the next thing. Um, and it’s, you know. Even if it’s something that looks like resistance, like let’s say sex Pistols or something, or punk rock, you know, how many months until you’re in the, the shopping mall buying these things that were resistant. And it’s, it kind of feels like that with CBD and cannabis and now mushrooms.

Joe Moore: Um, but, you know, one lovely thing mushrooms have for them is that you can grow them quite cheaply at home. I, I was trying to figure out how to grow pot years ago, and I, I was like, this is really expensive when I can just buy it for 50 bucks. Like, what am I doing? And then mushrooms came along as like, oh, I could grow forever for $300 forever.

Joe Moore: Forever. That’s crazy. What is this about? I’m gonna learn how to [00:06:00] do that. And of course I started with the, you know, most exciting kinds and then worked towards gourmet and, um, you know what, uh, do you have a, do you have a title for things like, do. Medicinal mushrooms, like we say, medicinal mushrooms here, but it’s like, you know, it’s not medicine in the same way that antibiotics are medicine

Oli Genn-Bash: yet.

Oli Genn-Bash: Yeah. So the term that I use is functional mushrooms and sometimes that can confuse people. ’cause there’s the term functional medicine, which for me is, is a, is a useful area to explore because essentially it’s, there are different systems in our body and any system requires certain things to be functioning properly.

Oli Genn-Bash: And how I understand it with a lot of what’s happening with the mushrooms, I think with the recent research that fascinates me about psilocybin mushrooms in extending your lifespan. Okay, [00:07:00] so that’s happening on the mitochondrial level. On the cellular level, that’s. There’s something going on where, and, and you see that widely with the different types of functional mushrooms, where it’s really getting into the building blocks of these different systems in your body where if we start to understand them, then we can really arm ourselves with a, a new way of preventing dysfunction.

Oli Genn-Bash: And the more I explore with all fungi, I kind of understand that disease presents itself in the body where there are cells which aren’t functioning properly, and then we call it, okay, it’s liver disease, it’s heart disease, it’s whatever it is, but it’s on a cellular level, there’s things which aren’t quite working properly.

Oli Genn-Bash: And so I do think, and you know, I guess my, my entry point into the functional mushrooms has been the psychedelic mushrooms has really been. [00:08:00] Quite powerful experiences with them where I have understood directly that they are here to sort stuff out on all these different levels. You know, we see it on an industry level with food, agriculture, medicine materials on the spiritual level with the, the psychedelic mushrooms.

Oli Genn-Bash: And for me, the psychedelic mushrooms pointed me towards the wider functional kingdom where they just said, look, you, you know, if you, if you want to be enthusiastic about mushrooms, what better way than to have a psychedelic experience in the Woodlands where the mushrooms are telling you, look, everything’s connected.

Oli Genn-Bash: Go forth, go explore this world of fungi. Because it does seem that there’s a lot of different areas when it comes to wellness, especially in health and, and preventative disease where they can sort stuff out.

Joe Moore: Um, yeah, [00:09:00] it’s a funny, it’s a funny conundrum. We’ve kind of like walked our way into this, um, kind of problem. It’s like, um, this idea that, um, that new product is gonna fix us, that new thing getting sold to us is gonna be the thing that pushes me over to the edge. You know, sometimes it is for some people, um, and we have some con contemporary pharma examples of that.

Joe Moore: Um, but, you know, it’s not really the case often with like this natural health thing where it’s like, oh, just throw more turmeric or CBD or matcha or mushrooms or whatever, and it’s like, oh, maybe we actually need change as well. Um, and let’s, let’s pull some things out that are actually kinda harmful, which is kind of, I think part of that functional medicine frame.

Joe Moore: Um, or functional mushroom frame, which is like, what’s, what’s harming us at the same time as we’re trying to heal? Do you kind of get into that much?

Oli Genn-Bash: Yes. I [00:10:00] overwhelmingly, what I say to my clients on, on all the different levels is, look, these mushrooms can help to unlock new ways of living your life. Um, for me personally, I’ve, I’ve gone down a journey where my health in general just seems to have been massively improved.

Oli Genn-Bash: The, the more that I consume these mushrooms in this intentional way, um, you know, it, it allows, I. I think there’s a lot going on with your gut bacteria. I’m, I’m sort of nerding out quite a lot about gut bacteria and, and I just think mentally, physically, there’s a lot going on and mushrooms seem to be unlocking a lot of what’s going on there.

Oli Genn-Bash: And [00:11:00] when you are modulating your gut bacteria, especially with these fungal polysaccharides, you are digesting your food better. And not only that, when you are modulating your gut bacteria, you desire healthier food and you get put off the food that is going to discourage that healthy microbial growth.

Oli Genn-Bash: So again, it’s kind of coming back to just this fungal mindset. It’s like, yeah, if we actually think like nature, if we think in these, these mycelial ways or, or fungal ways, then we can understand, okay. There’s a balance to be had. And actually we can encourage good growth inside of ourselves that will help to keep things ticking along.

Oli Genn-Bash: And I do think you start to clear out this junk, if you are engaging with your cellular system, with your [00:12:00] mitochondria, it is actually having this function of strengthening your oxidative, um, you know, the, the health of, of this kind of renewal of, um, anti-aging, of preventing certain disease. So I am quite, I wouldn’t say evangelical, but I do stress it quite a lot in my consultations is that, look, you, you need to think about your health on this wider level, on, you know, all the different things.

Oli Genn-Bash: And it is not to, um, shame people. It’s, it is more the opposite. It’s more to empower people that. I’ve always spoken about these things as allies, that, that came along quite quickly with my psychedelic use. I was like, oh, okay. These are, you know, they’re, they’re pals. They’re really here for us. Okay. So if we get on board with the fungi, then they’ll start to, they’ll be kind to us and they’ll, you know, we’ll go gently.

Oli Genn-Bash: It’s not, you’re not going [00:13:00] in and changing your lifestyle drastically. You’ll start to incorporate things which are conducive to that fungal lifestyle.

Joe Moore: So how did mushrooms first enter your life in a meaningful way, and what was the turning point that made you want to kind of really dedicate yourself there

Oli Genn-Bash: in a meaningful way? It was, I dunno if a stroke of luck or, you know, my first year of university at, uh, Kent University in Canterbury, they were growing literally 10 minutes walk.

Oli Genn-Bash: The, the University of Ken is, uh, is situated, uh, around a bit of farmland and yeah, you just walk and Canterbury in the, in the sixties and seventies was quite a psychedelic, uh, place. It was the birth of the progressive rock. It was known as the Canterbury Scene. University of Kemp was [00:14:00] quite a left wing revolutionary university, and I do think probably, you know, the fact that mushrooms seem to grow quite nicely around that area might have had something to do with it.

Oli Genn-Bash: And it just, quick bit of trivia first.

Joe Moore: So I, I have, I have Chaucer stuck in my head as like Canterbury Tales. Oh yeah, yeah. Um, kind of like a historical moment. Is Canterbury historically significant before, um, Rox scene kind of popped up or geographically important to uk?

Oli Genn-Bash: Yeah, so it’s the. The, the center of the Church of England, and it’s cool, been, been culturally significant for at least a thousand years.

Oli Genn-Bash: It’s got the oldest Christian Church in the world, uh, St. Martin’s church in Canterbury, and it has so many of these amazing [00:15:00] historically significant places. Um, you know, Caesar attempted to, to take it a couple of times and it was really difficult, and then eventually it was Romanized and um, so there’s a lot of Roman history there.

Oli Genn-Bash: Um, Canterbury Cathedral is, yeah, that’s the, the home of the, the Church of England where the Archbishop sits. So it is incredibly, it’s a UNESCO World Heritage site, so being there for university was quite amazing and I still have connections there. Some of the friends that I have there are. Some of my dearest friends, some of the most amazing, wonderful people, and there’s an energy there, which is, um, quite magical.

Oli Genn-Bash: You know, there’s the idea that the Canterbury Cathedral itself was built on a lay line. Mm-hmm. And you do feel this weird pull. There’s, uh, right around the cathedral, there’s a few different streets, which just all seem [00:16:00] to convalesce into this weird energy, and you feel yourself being drawn. And that was an interesting place to trip.

Oli Genn-Bash: You know, the, the university as well, being right around farmland and woodland. You Yeah, it was, it was just amazing. You really felt that natural kind of psychedelic connection and then Yeah. Culturally, I think. It just became that. And there’s still certainly that scene to a, to a certain extent, um, it has been made quite difficult.

Oli Genn-Bash: The Church of England has, you know, the, the cathedral owns everything within the city. W and they’ve made it quite difficult for the creative scene. There’s been noise complaints against venues. They want to keep it like a, a touristy, uh, a city, even though it’s, you know, it’s kind of town size, but they call it a city.

Oli Genn-Bash: And, [00:17:00] but you know, there’s, there’s still that heartbeat of the magical, um, surroundings. There’s a, a local festival called Smugglers Festival, which is, is quite small, about 2000 people. But it’s, it’s just an opportunity for all of these kind of psychedelic Canterbury and, uh, people from the, the local areas to.

Oli Genn-Bash: Come together. Run. Yeah. I, I, you know, I still visit and, um, I think having psychedelic experiences there, obviously that, that kind of has an imprint on your, um, you know, the, the connection to a place, right?

Joe Moore: Yeah, absolutely. Is it, um, somewhat similar to the US and, and where like these things are growing sometimes outdoors.

Joe Moore: Um, and it’s, you know, you’re not necessarily gonna get, um, in trouble if they’re growing in your yard, [00:18:00] but like after you could pick it and put it in your mouth, like with intent of putting it in your mouth, is that kind of a crime that anybody’s been popped for?

Oli Genn-Bash: So you do occasionally get reports of, you know, you have to be careful if you’re out on someone’s land and you are picking and you’re quite visible.

Oli Genn-Bash: There has been reports of, you know, police being called. And there’s the joke of the grazing loophole in the UK where it’s the law is once you pick it, then that counts as human intervention. So then if you’ve got down on all fours and just ate the mushroom straight out of the ground, then you wouldn’t technically be committing an offense.

Oli Genn-Bash: And so, yeah, you know, cultivation is, is a really interesting one. And I think you, you touched on this where quite a, a revolutionary thing to do in this country is to cultivate. And, [00:19:00] uh, if you have the space and, and you’re able to do it, I think more people are starting to realize, okay, we can. You know, it’s actually less risky to, to grow in your, um, in your bedroom rather than be out on someone’s land picking and risk, you know, the owner of the land calling the police or, yeah.

Joe Moore: Fascinating. Um, so beyond helping clients kind of, um, figure out how they want to include this stuff, or the most skillful way for them to include this stuff in their products, like what are you focused on right now? Is it, is it ecology or policy or, or health generally?

Joe Moore: I am,

Oli Genn-Bash: I am focused on, I guess health from a simultaneously individual [00:20:00] perspective and then the, the collective perspective. I think that. Health stems from the community. And I think in just even basic senses, not, not necessarily talking about supplements or functional mushrooms, but just from the food that we, in the UK generally, there’s a lot of food poverty.

Oli Genn-Bash: And I think accessing good quality food is quite difficult. I think the UK gets a reputation for having bad cuisine. Um, if you can afford it, you can eat amazing food in this country.

Joe Moore: Mm-hmm.

Oli Genn-Bash: Um, and, and I mean, British food, not, not just, you know, the, the different amazing culinary cuisines that we have here.

Oli Genn-Bash: Um, so then from a community perspective, it’s, it could be that. [00:21:00] People aren’t necessarily getting good health. They’re not encouraged to, to get good health. They don’t necessarily have access to education about cooking. They might not be culturally connected to any sense of, of cooking. So the food they might be eating might just be,

Oli Genn-Bash: you know, what we call ready-made meals in the uk. Something that you just put in the oven and there’s, there’s difficulty there if you try and encourage it. You are, you are often seen as, because the class system is so entrenched in the uk, if you, you have to be quite sensitive when you engage in things like food education because you can come of it from a place of privilege where you might have grown up with access and to knowing how to cook or come from a culture where these things are encouraged, uh, where you know, you might be a kid and included in the whole process of cooking.

Oli Genn-Bash: [00:22:00] So then I think, okay, if we look at supplements, functional mushrooms, health, preventative health, that has a lot of barriers. Even more so than food. You know, it’s, it’s quite expensive buying functional mushroom supplements. So then you have to be quite sensitive when you are engaging conversations about things like gut bacteria.

Oli Genn-Bash: For some people that’s so far off, but actually that could be a really good way to maybe, you know, foster good connections. You might look at. Yeah, as I said, other societies where they’re, where they’re eating these types of food, which is just encouraging kind of togetherness or societies where people are eating together more and, and then we can look at the wider health stuff, I think.

Oli Genn-Bash: And I think as well, you know, that relates to. My interest in the psychedelic space where there’s been a [00:23:00] lot of focus on the, on the individual. And I think it’s really important for me. I’ve had transformative experiences often times on my own, you know, especially where I’ve been able to go really deep and really get, you know, not necessarily to the bottom of stuff, but really start to kind of grapple with things.

Oli Genn-Bash: And then I think, okay, what’s happening with the wider community? You know, what’s happening with my, uh, family members who aren’t engaging in these experiences? I have, I, I come back to that place and, and that, you know, that goes for even God, things like fermented food. I’ve had conversations with family members and friends where if I mention sauerkraut, they kind of look at me weirdly.

Oli Genn-Bash: So there’s, there’s these barriers where it’s like, hey, if we were all eating sauerkraut and taking a microdose occasionally, or a macro days once or twice a year. We might be more connected and then looking at, and I’m [00:24:00] not, I don’t want to romanticize, right? I think that happens a lot when it comes to other cultures that like, okay, we romanticize psychedelic use and say, oh, these tribal cultures are all connected.

Oli Genn-Bash: And that’s not necessarily always the case, but I think it could maybe foster a bit more connectivity in, uh, you know, places where we’re so disconnected.

Joe Moore: I think back to how obnoxious I must have been when I was pushing a lot of the stuff in my earlier days and, you know, just the total kind of ignorance or how I sounded and kind of like informational privilege was kinda operating with, and, and you know, sometimes also economic privilege is just wild.

Joe Moore: So I’m, I’m glad to hear you’re kind of taking, um, systems aware approach here. Mm-hmm. I think that’s one of the few ways we can really make up a big dent is being systems aware.

Oli Genn-Bash: Yeah, absolutely. I’ve been recently collaborating with someone called Jess [00:25:00] Jorgensen, who runs an organization called Foresight, and it’s related to the field of, of futures thinking of, of foresight.

Oli Genn-Bash: And it really does go into to this whole idea of, okay, how can we utilize this mycelial thinking? Uh, another organization I’ve been collaborating with is Mycelium Hub. Uh, they’re based out in Sweden and they run events. Again, it’s, it’s based around this idea of mycelial thinking natural law. Okay, how do we

Oli Genn-Bash: utilize systems which might be able to provide more meaning, create. Scenarios where it’s win-win, where it’s not necessarily competitive. Where I think people might be feeling exhausted from working in jobs where they have to compete all the time, where they might be working [00:26:00] 70 hour weeks where okay, they’re earning lots of money, but after a while they just kind of think, okay, what am I really doing it for?

Oli Genn-Bash: And I think the benefit of psychedelics is bringing you back into that inner child is, is helping you to find what really excites you and, and bringing that into your adult life. Doing that kind of re-parenting where, okay, now we’re at the right place at the right time. And I, I dunno if it’s a coincidence, but mushrooms seem to be.

Oli Genn-Bash: Popping up now in, you know, the, the general collective consciousness in all these different ways. So maybe now is the right time for the people who are interested in these spaces to come forward and utilize that enthusiasm. Because, you know, I, I spend a lot, when people ask me what do I do? I just like, you know, I spend a lot of my time having meetings with people in the [00:27:00] US and India and Thailand, people that are just working in the mushroom space and literally people on LinkedIn will send me a message saying, Hey, let’s chat about mushrooms.

Oli Genn-Bash: I go, brilliant, let’s do it. And, and it’s just, it’s great. And, you know, I try and, uh, you know, make it work with teaching and consulting, but generally it is that childlike enthusiasm. And, you know, if you see me in the, in the woodlands where, you know, if it’s been raining at the right time of the season, I will.

Oli Genn-Bash: I’ll just think back to kind of being a child in, in the forest. Okay. And just feeling the fun of finding a mushroom that looks really interesting and taking a photo of it, or, you know.

Joe Moore: Yeah. How do you describe this kind of inherent sharing kind of thing, in essence, in the mushroom community? Because I find it just so [00:28:00] alien to how we kind of wanna operate most of the time in our culture.

Joe Moore: Um, but everybody wants to teach everybody how to grow or everybody wants to talk about identification or whatever it is, and it’s just infectious. But it’s, is it that childlike thing that we just want to share how wonderful this is?

Oli Genn-Bash: Yes, I think so. And I, I do also think, uh, they, they, they might be hijacking us, you know, who knows in this, in this way of.

Oli Genn-Bash: Symbiotic relationships where we can’t underestimate the fact that there might be intentionality, there might be agency. I’m always stunned every time I consume psychedelic mushrooms that there’s a sense of agency to them. It just, it just baffles me. And then when you look at the, the traditional Chinese medicine, [00:29:00] um, they’re almost kind of personified.

Oli Genn-Bash: They’re, they’re called these names, which, which gives them person that gives them agency. And yeah, they, they might have a plan for us. I don’t know. You know, um, people like Terrance McKenna kind of think they, they came from space. They might have come and, and colonized us. They’ve done a really good job.

Oli Genn-Bash: We’ve, I find it interesting that, you know the reason. We can benefit from them is the same reason that they can cause us lots of problems. Spores can cause us asthma, yeasts, molds, they can be really bad for our lungs. So, ’cause we’ve co-evolved with them this way. Then our bodies also have receptors which can respond really well to the psychedelic parts of them, the functional side of them.

Oli Genn-Bash: So yeah, it might be, uh, [00:30:00] yeah, sort of, I dunno, fungal panspermia.

Joe Moore: Yeah. That’s great. Um, we should, I should probably do some sort of conference on that someday. Just kind of Terrance McKenna in review. Yeah, right. Like that fungal pin spur me think is obviously something like it’s core to his thinking, so,

Joe Moore: yeah.

Joe Moore: In the past you’ve, you’ve talked about mushrooms as more than organisms. How do you personally understand their role in consciousness healing and meaning making? Big question. I know, but wherever you wanna go with that.

Oli Genn-Bash: There’s an, there’s a, there’s a feeling of familiarity about them that I find really fascinating. I think I’m not someone that’s actually gone through, uh, the DMT experience. I’ve kind of touched on the [00:31:00] edges of it, and with powerful experiences with mushrooms, there’s something

Oli Genn-Bash: where it just feels, you know, I, I’ve had experiences where I’ve had this direct communication, which feels like they are welcoming me home. They say like, oh, welcome back. Quite similar to DMT.

Oli Genn-Bash: So,

Oli Genn-Bash: yeah, it could be that.

Oli Genn-Bash: I don’t know, it it, it feels like they know about us. It doesn’t. I, I think back to Kalindi e who was a proponent of the 20 plus dried gram experience, and I had the opportunity to spend a bit of time with him [00:32:00] talking to him. And I’ve, I’ve never got close, you know, never that, that level is, I think, you know, from speaking to Clin, it’s a whole different kind of level and not in any, as he said, kind of pissing contest where it’s just recognizing that if you are putting more fuel in the rocket, then you’re gonna go further into space.

Oli Genn-Bash: Um.

Oli Genn-Bash: And from speaking to people like him and from my own experiences and, and having this kind of familiarity and having this sense of, you know, I, I had on an experience probably clo close to about four dry grams of Liberty caps, which are, um, really interesting. But, you know, outta all the, the different mushrooms I’ve, uh, had experiences with and different psychedelics, I’ve not really had any extraterrestrial [00:33:00] experiences other than with Liberty caps.

Oli Genn-Bash: And it always feels like this sense of them saying, oh, welcome back. We’ve, you know, we’ve waited for you. So then there’s a feeling. And my response to that is this profound sense of, okay, right. This isn’t just my imagination. This is, this is something happening. This is something going on. This is some core thing that they are here to, to, I don’t wanna use the word progress.

Oli Genn-Bash: Um, that can be a dangerous kind of path. Go down, talking about progressing and that kind of means that there’s a place that we are meant to get to. But I think what they can do, and I think they are, it does seem they are integral to[00:34:00]

Oli Genn-Bash: helping us to undo a lot of the really difficult experiences that humans have gone through. It’s kind of insane being a human, you know? Um, I don’t want to say we’ve got it worse than animals because we mess up the world and we kill a lot of animals. Um. But we just have all this stuff going on. You know, you are sat in front of a bookshelf, I’ve got a microphone here and a cup of tea.

Oli Genn-Bash: It’s like all these different crazy levels of experience and, and so I think it can be, you know, this intense, uh, time being a human. So maybe the mushrooms know about that and maybe they’re, you know, I’ve, I’ve really had these experiences quite consistently where it feels very soothing and it really just feels like I’m getting these messages of,[00:35:00]

Oli Genn-Bash: you know, we are here, don’t worry, you know, we’re sorry, but you are, you are, you’ve gone through this. And, and, and when I say that, it’s often felt in a collective sense. It’s not necessarily always about me, even though it is about me. But then it’s this understanding of, you know, we are all this one thing and the mushrooms are here saying, yeah.

Oli Genn-Bash: We get that, we get that you are the individual, we get that you are the collective and we’ve got you.

Joe Moore: Hmm. I love that. Thank you for going far out with me. Um, no worries. Not always comfortable doing it in public. Um, but I think it’s important to like kind of discuss this stuff and say, Hey everybody, like we’ve had a lot of experiences or a handful of experiences and we’ve been studying this stuff for a while, and we come back sometimes with interesting perspectives that are gonna challenge you a little bit.

Joe Moore: Certainly challenge us landing [00:36:00] here. Mm-hmm. But, you know, um, yeah. So a lot of people are mushroom curious but intimidated. What’s your kind of like gentle onboarding approach in any of the areas of ology?

Oli Genn-Bash: The first thing I always want to say is that not to be afraid that mushrooms are, mushrooms are poisonous.

Oli Genn-Bash: It’s like, yes, some mushrooms are poisonous. I think in, in the UK especially, we have a lot of microbia. I think that probably came out of the Victorian era. We, and, and also witches. Uh, and that whole thing has a big, you know, the, the toad stool has a big part to play in that where, you know, I won’t go down the AM route, but everyone for the most part kind of thinks like, oh, I won’t, won’t touch Amita ’cause it’s toxic.

Oli Genn-Bash: And then, you know, you have the minority of people that are progressing the microdosing route with Amita, you know, quite successfully, I [00:37:00] think. Um, so that has, I

Joe Moore: blowing up in uk similar to it is here,

Oli Genn-Bash: not similarly in terms of the products. We don’t have that same kind of freedom. But certainly in terms of the more people are talking about it, there’s more events happening.

Oli Genn-Bash: And I’ve seen some people with products that are starting to enter the space in a kind of grayish area, um, where it’s not being recommended for human consumption. But, um, yeah, there’s certainly a lot more talk about it and, and people I know personally that are real fans of it.

Oli Genn-Bash: Um, and I’ve, you know, I’ve personally as well had had an interesting time, um, with the microdosing. It’s, it’s quite interesting. Um, obviously very different to microdosing, uh, [00:38:00] psilocybin mushrooms.

Joe Moore: Mm, mm-hmm. Yeah, it’s a, it’s an interesting one. It’s, it’s kind of gentle, but yeah, you’re right. Like this idea that all mushrooms are toxic is pervasive in a lot of areas and we should be afraid of them.

Joe Moore: Um, yeah, I think that’s, you know. That’s a classic one to smush, do you, do you then start kind of saying like, Hey, look at these pretty ones or look at these ones that you could eat in a salad or with spaghetti or something or how do you like to to go from there

Oli Genn-Bash: often? I think predominantly people are getting interested in lions mane for the cognitive benefits.

Oli Genn-Bash: I dunno if it’s the same in the US but in the UK I think COVID and um, just generally people are feeling a bit of malaise, a bit of disconnection [00:39:00] and maybe feeling overworked, quite tired. So often I’ll see Lion’s mane is, um, the mushroom, which is going outta stock the most in health food shops and that’s quite a good one because it’s really tasty as culinary mushroom.

Oli Genn-Bash: So. Now we’re starting to see Lion’s Mae being sold in the supermarkets, uh, next to the shiitake and oyster mushrooms and the butter mushrooms. People are starting to get on board with it, and then I can say to them, Hey, you know, it’s great eating the lion’s Mae mushroom as a steak, but if you extract it with hot water, if you do extract it with hot water and alcohol, you might be able to get some more benefits out of it.

Oli Genn-Bash: And eating it as well is, is really good for you.

Joe Moore: So I see on your Instagram you have this post here. Um, this is from a while [00:40:00] ago, back in early August, I think, uh, could mushrooms actually help replace alcohol? Like, one of my kind of projects is how do we, how do we erode the market share consumption levels of alcohol a bit. I think Denver recently was rated this number two most heavy drinking city.

Joe Moore: In the United States. And, you know, I don’t, I don’t know if that’s accurate, but you know, that’s what I read yesterday on some website. And I, I think like, um, it’s, it’s harmed me and it’s harmed people around me, um, for a long time. And I, you know, I, what does a healthier culture look like? So obviously looking to alternatives is interesting.

Joe Moore: So, yeah. What, where did you land on this post? Maybe, you know what post I’m talking about here?

Oli Genn-Bash: Yeah, I think it’s, I think it’s difficult because drinking culture is so heavily embedded in, in the UK even, you know, in, in all different areas. Um, even in the psychedelic culture, the wellness [00:41:00] cultures, people aren’t necessarily not drinking alcohol.

Oli Genn-Bash: I’m starting to see a growing trend where people are, um, reducing their alcohol intake or. You know, I am coming up to three years of, of not drinking any alcohol. And that was, that was mainly because I, I play in a, a psychedelic rock band and there’s just a lot of alcohol around it at gigs. And it got to the point where I never really drank that much, especially at university.

Oli Genn-Bash: My first few years of university exploring mushrooms, I just didn’t really care, you know, and other things like, uh, LSD in particular, I was just not really interested in alcohol. And then I, in my mid twenties, lived in Australia for a year and accessing psychedelics in general. [00:42:00] Um, I wasn’t, you know, uh, I was just backpacking and it was like, whatever it was that, that sort of culture.

Oli Genn-Bash: So I, I got into drinking and then playing in a band. It was just becoming too regular and I just needed to nip it in the bud and, and through, you know, consuming a few different protocols with, uh, plant medicine, not actually, well I was consuming functional mushrooms at the time. Um, and then really I started down the, the route of quadriceps for treating fibromyalgia.

Oli Genn-Bash: And when I started to increase the doses, because I was dealing with a lot of fatigue and quadriceps is amazing for managing fatigue, but I was finding that I needed to use quite high doses. But in using those high doses, my mood was just being really [00:43:00] elevated. So in as much as there was the physical aspect, I was just.

Oli Genn-Bash: Feeling great. And I was also combining it with a lot of cacao. So I was getting, I think that dual effect from the cacao and the quadriceps. And interestingly, I’ve spoken to people who’ve researched quadriceps and they said there’s a relationship to cords and the heart chakra. So thinking about cacao as well, perhaps there’s that real synergy which might be, uh, a bit untapped.

Oli Genn-Bash: And I personally find if I am, you know, I’ve been at social events where I’ve been, yeah, consuming high dose of quadriceps and lines main, and I just feel really switched on. I just feel lively. I don’t feel anxious, I don’t feel fatigued. And I think that’s a big thing for me. What I found as well, with other people with long-term health conditions, they can find it [00:44:00] hard in social situations.

Oli Genn-Bash: Mainly because it’s like, okay, there might not be somewhere for them to sit. All right? If they do go and sit, okay, well, they’re not involved in the situation, so then they’re standing up and then they might feel a bit tired. So I think that’s why microdosing is quite good in these situations. And then as well with the functional mushrooms, I find if I’m consuming, yeah, as I said, high doses of lion’s mane quadriceps.

Oli Genn-Bash: With something like cacao, I am generally feeling pretty good. You know, I’m, I’m, I’m not getting those dips in my mood or my energy, and especially for social anxiety. I just think it’s great. I think quadriceps is a really undertapped one. It, it’s, it’s good for, you know, it’s traditionally recommended for libido.

Oli Genn-Bash: Okay. So I think what that means is it’s like, it makes you feel more comfortable in yourself and more confident in [00:45:00] yourself, and. Able to engage more and you are naturally more engaging. You are, you, you might just be carrying yourself differently. Your body language might be a different, a bit different.

Oli Genn-Bash: So I think these, these mushrooms are really untapped. I do think we need to use quite high doses. I do think there’s a lot of, I dunno about a lot, but there’s some interesting work being done, especially in the us Um, there’s a brand called Arian. They’re doing interesting work with looking at bioavailability and looking at, okay, can we use things like liposomal encapsulation to help the body to recognize the compounds within the mushrooms better?

Oli Genn-Bash: And, you know, there’s, there’s a lot of opinion that’s divided. People saying, look, you just need to consume these mushrooms in a more traditional way. [00:46:00] But I think the more work that’s being done with them will start to be able to really utilize the benefits. And then we’ll start to see, okay, actually, um, I’m really noticing the effects of certain products and, and the changes in my mood, changes in my energy.

Oli Genn-Bash: And I think as people start to move away from alcohol more towards psychedelics, other supplements, um, you know, I think things like Maca, it’s absolutely amazing. It’s not spoken about enough. It’s one of my favorite supplements. Um, so I think, yeah, these, these kinds of things can help replace alcohol.

Oli Genn-Bash: ’cause people are starting to realize, you know what, actually, the more we start to engage with the world, the more we start to pursue things which really interest us. We realize that actually alcohol is, you know. It really does hinder things. You know, I, I dunno how [00:47:00] people do it. Like, I, I dunno if I had a thing where I don’t process alcohol properly, but I would start to feel hungover before the night was over.

Oli Genn-Bash: Mm. So then I would just be like, ah, it’s just not, you know, I would, I would try and do it, try and keep up, but I would never get to the point of being drunk. I would just be consistently, you know, when I lived in Australia, I think for kind of three months, more or less, every night I was having a couple of beers smoking a joint after work, I would never get drunk because I would just not, if I got to that point, it would just be awful.

Oli Genn-Bash: And when I was younger, you know, every time when I got drunk, it was just always just, you know, awful experience.

Joe Moore: Well, thanks for all that I. I really hope we can flesh that out a little better and, um, I, [00:48:00] yeah. Hopefully save people money both on the front end and the back end from alcohol. Um, yeah, and also I just mm-hmm. Please, just, just,

Oli Genn-Bash: just to add to that is like, okay, if there are psychedelic events, you know, I was, I was at a psychedelic event where someone from the US said, wow, you know, I didn’t realize British psychedelic people like alcohol so much.

Oli Genn-Bash: And I just said, look, British people in general really like alcohol. And I think there is something to be said for that. It’s like, okay, if, if we are engaging in events where there might be sensitivities there where people might have had addictions, we need to be quite careful about okay, after parties where there is lots of booze going around, or just events in general where there’s like booze in sight where people are being quite conscious now and they’re utilizing psychedelics to overcome difficult experiences with things like.

Joe Moore: Right. Um, [00:49:00] I was, yeah, I was at a, like, I don’t even know if you can call it an after event, I guess it was, but yeah, a bunch of us went to a pub and the amount of drinking was, was staggering. And I was like, wow, amazing. And, uh, yeah, I think, um, you know, I used to drink a ton, right? Like I, I, you know, used to have not a great relationship to it.

Joe Moore: Um, it’s faded, thank goodness. Never really needed treatment other than, you know, maybe the accidental overdose on mushrooms once in a while. But, uh, you know, um. I think you’re right. Like being aware of who’s at these conferences and being kind of substance aware is, is really helpful. Like do, do you have good alternatives?

Joe Moore: Do you, do you maybe keep the alcohol off to the side so people don’t necessarily see it as much? Or, you know, what, what is the way to be, um, to do hospitality in a way that that feels good for you at the end of the day [00:50:00] and, you know, help somebody not drink if they didn’t wanna drink?

Oli Genn-Bash: Yeah, I think we’re, we’re starting to see more in these areas where it, it’s really great to see festivals in the UK that are alcohol free.

Oli Genn-Bash: I think there is the, the slight caveat there is like, from a musician’s perspective, uh, the, the music festivals kind of have to sell alcohol because if they don’t, then, you know, the, the industry is so tight. The festival industry in, in general is so tight that if you don’t sell alcohol it, your festival might collapse because actually ticket sales aren’t enough to help it survive.

Oli Genn-Bash: So there is some sense of, uh, allowances there to not sell alcohol out. Some of these more smaller, psychedelic focused, [00:51:00] wellness focused events in places like the uk having said that is really good to see certain companies, you know, in, in the mushroom space in particular, and I think in the adaptogenic space and tropic space that are producing products which are really helping people.

Oli Genn-Bash: And I think it’s, it’s amazing to see just more products and a lot of innovation and a lot of interest in different herbs and mushrooms and a lot of conversation about. Different ways in which people can really benefit from these things. There’s brilliant people in the uk like the Seed Sisters, la the Plant Scientist, um, and just a general good sense of herbalism, uh, in this country where people are connecting back to the land, connecting back to these kind of ancient roots, realizing, and also, you know, I think it’s different culturally in, in different [00:52:00] spaces.

Oli Genn-Bash: I don’t think the UK will ever move away from alcohol. I, I still think there’s a lot of that embedded even in the kind of psychedelic, pagan, hippie folk culture. Um, that will never go away. But I think people will start to u utilize alcohol and other things in a more conscious way.

Joe Moore: Yeah. Um, agreed. I, I just, yeah, in its right measure, um, is where I hope it heads.

Joe Moore: Um, so some stuff we didn’t really get into yet is this kind of future of mushrooms around kind of things like bioremediation, different kinds of, um, higher tech materials, like buildings using, um, kind of bricks made from mushrooms. Like, where do you think we’re gonna see mushrooms be in the next 10 years?

Oli Genn-Bash: I mean, we’re starting to [00:53:00] see a lot more happening in terms of material, clothing, fashion. I think it’s, it’s interesting to see where they, you know, it’s, it is interesting. We’ve got this whole thing of fast fashion and then mushrooms are coming in and there my CA way to slow things down and they’re like, no, no slow fashion.

Oli Genn-Bash: So that’s really interesting. I think we might start to. We establish our relationship with clothes and this idea of just kind of throwaway culture. Um, certainly regenerative areas where mushrooms are really fascinating. If you look at Michal Fungi in helping to fix the soil, and it becomes difficult not to just evangelize about mushrooms because it does seem like there’s all these different areas.

Oli Genn-Bash: You know, we’re seeing it with food, with Myprotein, we’re seeing it with medicine, uh, wellness products. So [00:54:00] it could be, you know, there’s, there’s people like Mark Olo from Myco Stories, Dennis Walker from Micropreneur. They gave a presentation last year at All Things Fungi Festival, where they were looking at the future of fungi.

Oli Genn-Bash: And it, it kind of seemed like, uh, you know, you’d be waking up into this. Fungal futuristic environment where everything would be fungi. Uh, I dunno how far away we are from that. I don’t know if we’re a long way from convincing people to eat things like myprotein, if you know the building material. I think it’s interesting.

Oli Genn-Bash: It’s like, okay, we can build things from mushrooms. Will it keep up with the needs of, um, society? Is it, is it something which is coming in at the right time to actually help steer us in the right direction? You know, I’ve seen [00:55:00] positive things if we look at like hemp, um, that can have uses, but then does it actually stand up to kind of this increasingly demanding society that we’re in?

Oli Genn-Bash: So I think we need to have balance, but, um, yeah, there’s a, there’s a lot of interesting innovations. Happening with, um, I think I saw someone creating a mushroom canoe. So, um, you know, there’s like different ways in which you can use it for building material, for, for all different kinds of things. Um, I think the, going back to my thoughts about psychedelic mushrooms, it does kind of seem like they are here at the right time to kind of clean things up and perhaps get us back to a state of, of balance.

Oli Genn-Bash: So if, if we, if we think more in terms of, you know, perhaps can we, can we try and apply every situation as radical as that might [00:56:00] be? Can we try and apply it with a psychological lens? If we, if we look at what’s going on, can we, can we think, okay, what would a mushroom do? How would a mushroom think in this situation?

Oli Genn-Bash: Um, that might require some. Uh, shifting. I don’t think in sort of, you know, like paradigm shift, I just think possibly in a more, maybe in a more metaphysical way, in an animistic sense, okay, let’s step away from this human way of doing things. Not in a radical sense of like, humans are bad humans, parasites.

Oli Genn-Bash: I just think, okay, we are one of many creatures. We are the dominant ones, but can we just kind of step our, you know, take our foot off the gas for a little bit? Because it’s quite clear things are out of [00:57:00] balance and people aren’t necessarily having a great time. I mean, I’m sure people with lots and lots of money are, I don’t know, I don’t even know if they’re having a good time.

Oli Genn-Bash: I think they’re just addicted to making lots of money. I think, you know, it’s like, don’t get me wrong, I have amazing relationships with people and wonderful unitive experiences. I think people at the moment in general find the world quite difficult. And I think we are looking for different ways to make things a bit easier for, for everyone and all beings on this planet.

Oli Genn-Bash: Where can we just come together in a sense? And again, this, you know, slow down. Um, there’s a saying, I think from Bio Aku Lafe, it says something like, the times are urgent, we must slow down. There’s like, okay, can we utilize this mycelial thinking? It is quite slow, you know, whenever [00:58:00] anyone speaks to me about cultivation and, um.

Oli Genn-Bash: Working with people like Darren LeBaron. You know, he always says this whenever anyone anyone asks him, uh, you know, how long will it take for the mycelium to colonize? It’s just like, well, it will, it will take as long as it takes. And actually, when you get into that mindset, then it becomes you, you do start to shift.

Oli Genn-Bash: You do think, okay, what are the ways in which we can, I guess my cate our thoughts? And, and maybe that is all happening. Maybe it is, okay, if you are consuming a lot of psychedelic mushrooms or functional mushrooms and there is things happening with your gut bacteria and your DNA and your neuroplasticity, then that’s gonna have a big effect on the way in which you engage with the world and, and what you think might be possible.

Oli Genn-Bash: So I do [00:59:00] think it’s fascinating just to see. I think there’s a, there’s a lot of money going into, um, you know, from, from quite big players going into this space. Um, uh, and people have really tracked this area to, um, see where the different innovation is. And I, I, you know, I’m surprised that, that people are, are able to just kind of track it so, well, you know, people like myo stories.

Oli Genn-Bash: Um, you know, when I look on LinkedIn, it’s just like, there’s always something going on. So I think it’s quite exciting and I think it is helping us to potentially reimagine things.

Joe Moore: Mm-hmm. Yeah. Um, and then Darren lab line, I’m just thinking about growing bags. Out and I losing my mind. I’m like six weeks in and I don’t see anything.

Joe Moore: And then it works out fine. Sometimes, sometimes, other times it’s a little ugly. [01:00:00] But yeah, like just, it takes what it takes and you can be in the perfect environment and have the perfect lab and be replicable, but most of us do it in our, in our homes. And it’s not a laboratory environment, a well controlled laboratory environment at all.

Joe Moore: Mobile continuation units. And all

Oli Genn-Bash: the, the funny thing was I, when I was, uh, cultivating during the pandemic, it was just quite funny because I was like, in this, in this shop picking up like disinfectant and gloves and masks and all this stuff. And I was just like, oh yeah, the poor pandemic’s really bad.

Oli Genn-Bash: And then going home, sanitizing my, my kitchen counter and setting up my sort of lab environment and.

Joe Moore: I never had the pandemic as an excuse. That’s lovely. Yeah, I had just deep paranoia at the store. Ah. Um, um, and then, so finally here as we kind of work towards [01:01:00] wrapping up, like what, what kind of things do you think the psychedelic movement could learn from mushrooms generally from like an ecological perspective or growth perspective or, or anything like that?

Joe Moore: Like, I, I know, you know, the psychedelic culture is, is often just an outgrowth of kind of, um, primary dominator culture, kind of what, you know, mechanical dominator culture. But what, what can we learn from mushrooms as, you know, a species?

Oli Genn-Bash: Yeah. I mean, it’s, it’s fascinating to see the psychedelic culture go the way it has.

Oli Genn-Bash: I don’t know. How much to this extent I kind of expected, or me and other people expected it to be. So, uh, dominantly capitalistic and, and huge amounts of money coming in from people like Christian Meyer and Peter Thiel, who I just won’t, you know, that’s the whole, and that’s a whole podcast, [01:02:00] uh, thing that I, you know, and, and the way in which we engage with psychedelics on a personal level and a collective level.

Oli Genn-Bash: Um, it does really matter. And I think with mushrooms, you know, for me, they, they kick my ass. That’s what I say to everyone all the time. It’s like, I am always, you know, and I’ve had quite a lot of experience with them, and I’m always going in with a bit of trepidation because I’m always just like, okay, there’ll be some kind of as kicking, there’ll be some kind of.

Oli Genn-Bash: Download. And I do think that, you know, I’ve had quite intense experiences with them. Not necessarily scary or, or difficult, negative, but just like, okay, you know, uh, sort of getting something like a telling off from a collective humanity experience where they’re just like, Hmm, sorry guys. You fucked up.

Oli Genn-Bash: You, [01:03:00] you know, you’ve just extracted you, you haven’t actually respected this amazing planet that you’re on. Which, which might be, I think, and I’m reading stuff in, uh, physics saying we like might be in this void, this planetary void. You know? It’s like, okay, so there’s, there’s nothing around us. Um, and we might be in a, in this really special zone and, and this place that.

Oli Genn-Bash: We really need to respect and like, however we’ve got here, whether it’s been fungal, panspermia, you know, there’s, there’s a reason why we’ve come here from wherever we’ve come from, however we originated here. So I think the mushrooms in getting everything going in, in being these primary decomposers, as Darren LeBaron says, getting the party started, you know, they, they come along where there’s just not things happening [01:04:00] and they start to break things down and life comes along and they do so much and, and without them, you know, I don’t want to overplay kind of like the Grand Mycelial network, but it does seem there’s a lot of these certainly localized areas in, in large parts of, of Forest where there’s these huge networks that are having these symbiotic relationships with trees.

Oli Genn-Bash: You know, there is parasitic stuff happening. You know, we, we can learn from that as well. We can understand, okay, where we might be parasitic and where to, where to kind of check that and guard against that and, and where it might not be useful and, and engage more with these symbiotic relationships and win-win scenarios where, why not everyone benefit?

Oli Genn-Bash: Why does it just have to be [01:05:00] billionaires, increasing share prices And, um, people just kind of feeling like, okay, well maybe I can’t access that type of healing that I, I might desperately need. How do I do that? Okay. Uh, and that might create more difficulty. So then with the. I guess getting back to these ideas of kind of natural, okay, how do we work with situations?

Oli Genn-Bash: What we’ve got to create situations where in general, kind of everyone can benefit in, in situations where possible. It’s like I’m not an idealist, I don’t think, I try and not think in these utopian terms I said in terms of progression, but it’s actually okay, what have we got now? What can we learn from different ways [01:06:00] of utilizing resources more efficiently?

Oli Genn-Bash: And um, creating systems where people can benefit economically from growing mushrooms or creating mushroom products. And so I think mushrooms do open up a lot of different possibilities.

Joe Moore: Wholeheartedly agree. They do. Yeah. Um, Americans that wanna learn more, it’s a really cool organization called ERs here in the us um, that’s doing some really cool stuff around this, um, bio.

Joe Moore: Um, what else is interesting? Oh, there’s just so many interesting people doing interesting stuff, uh, around mushrooms. So just learn, learn what you can. If you wanna grow, grow, if you wanna have some really amazing innovation, go for it. It’d be really fun to have it. Yeah. So Ali, thank you so much for being on the show.

Joe Moore: Where can people find your work online?

Oli Genn-Bash: Thank you, Joe. Uh, you can find [01:07:00] me at thefungiconsultant.com. Email me at oli@thefungiconsultant.com Check me out on LinkedIn and Instagram as well at the Fungi Consultant and at Oli Ash.

Joe Moore: Right on Oli. Thank you so much and hope to do it again in the future.

Joe Moore: Thank you so much, Joe. Appreciate it. Absolutely.