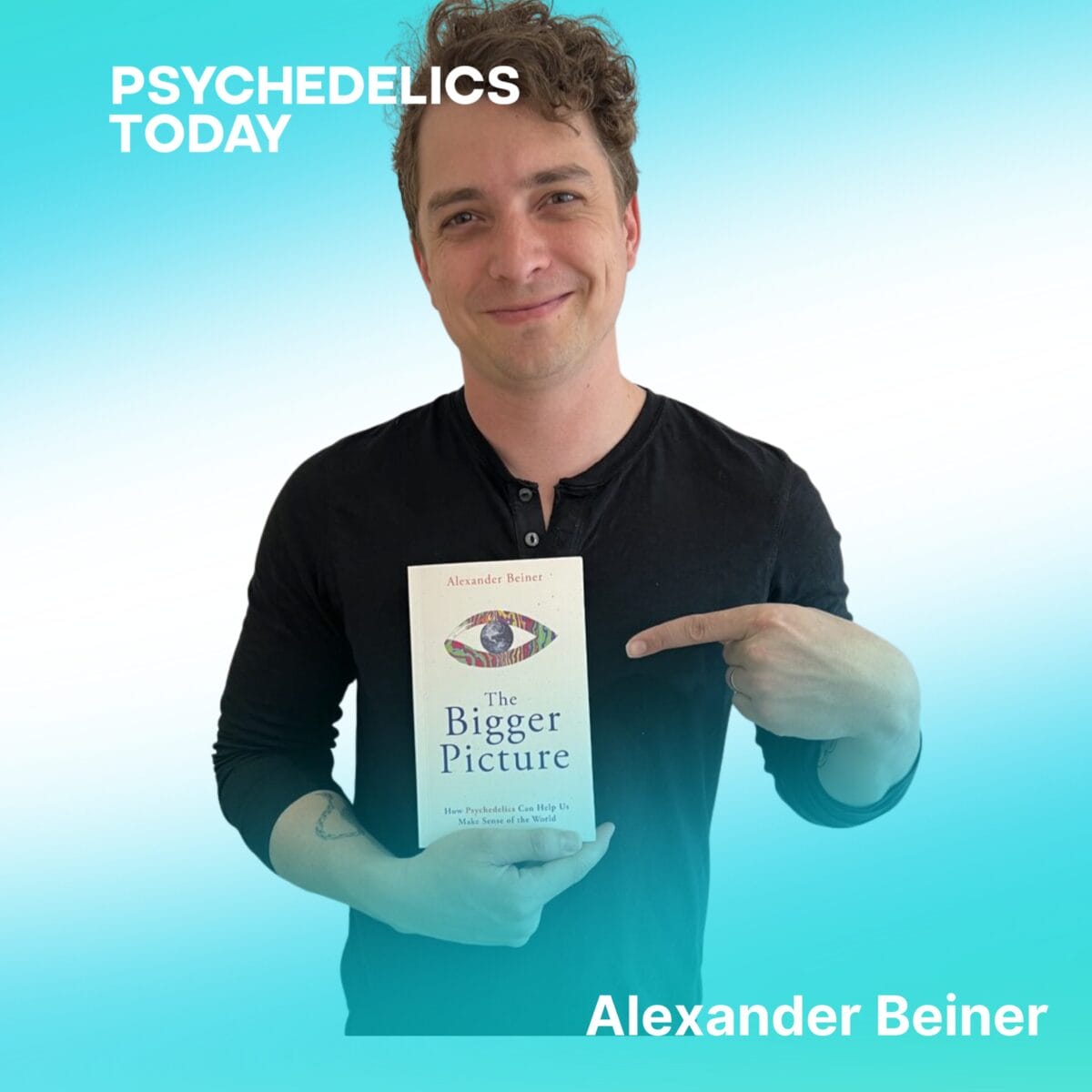

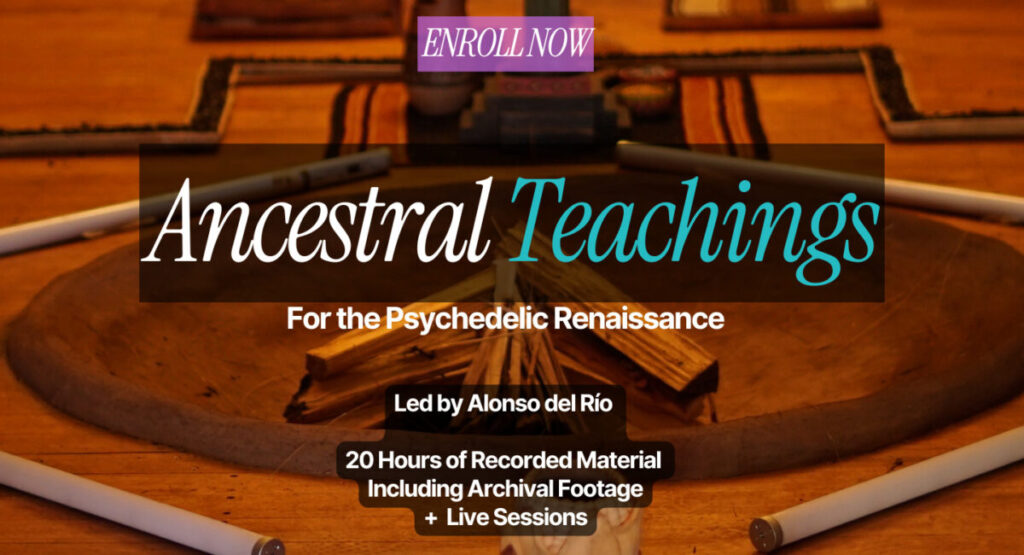

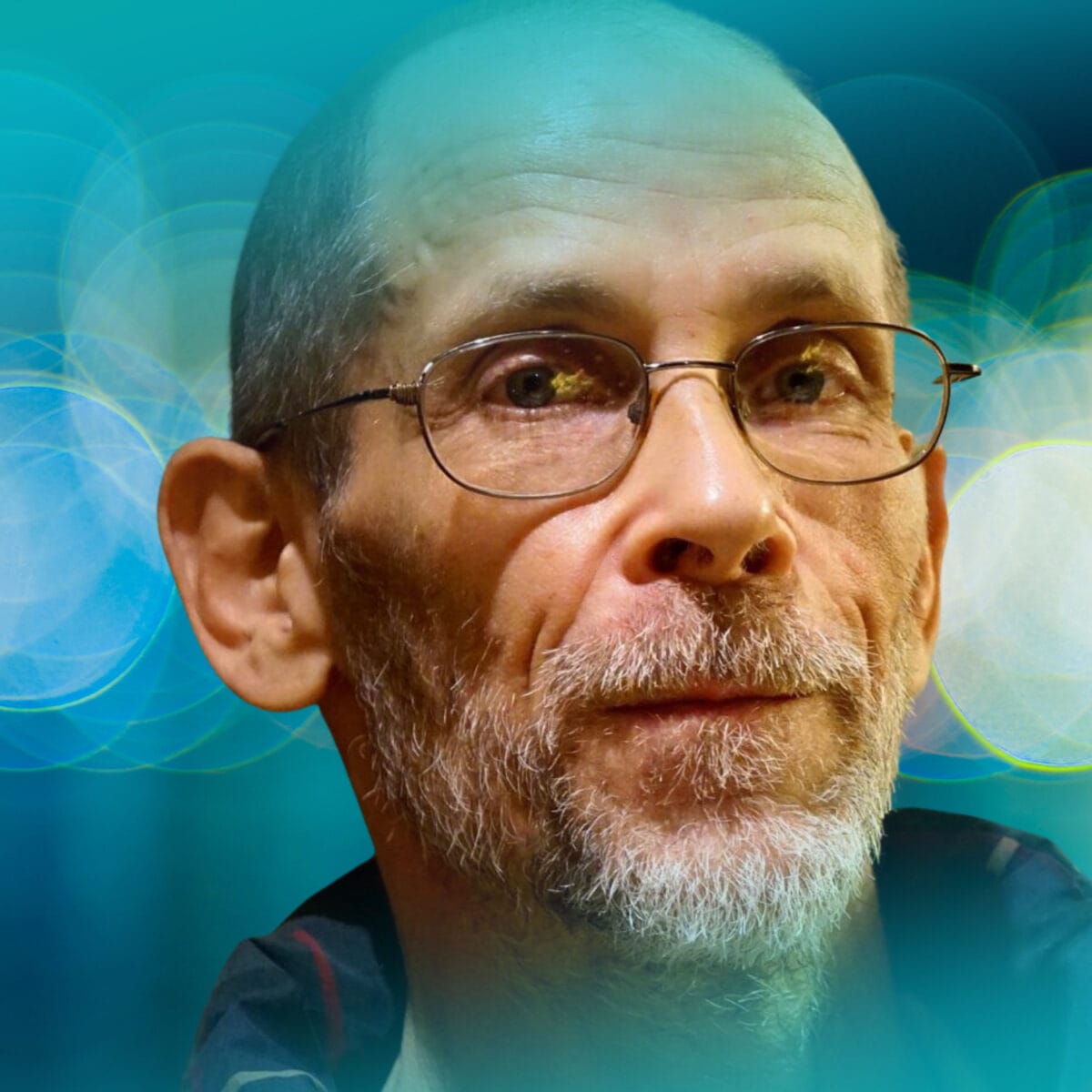

Manvir Singh PhD joins us to unpack what shamanism means and why the term matters now. Singh is an anthropologist and author of Shamanism: The Timeless Religion. He argues that shamanism is not limited to “remote” societies or the past. Instead, it reliably reappears because it helps humans manage uncertainty, illness, and the unknown.

This episode is relevant for the psychedelic community because “shaman” often gets used loosely, or avoided entirely. Singh offers a clear framework for talking about shamanic practice without leaning on romantic myths, drug-centered assumptions, or rigid definitions that do not fit the cross-cultural record.

Early Themes With Manvir Singh

Early in the conversation, Manvir Singh explains why many classic definitions of shamanism break down when tested across cultures, including in Siberia where the term originated. He discusses how popular images of shamanism often center “soul flight” and fixed cosmologies. However, ethnography shows more variation, including possession, spirit proximity, and different ways practitioners describe altered experience.

Singh also traces his path into anthropology, including long-term fieldwork with the Mentawai people off the west coast of Sumatra. There, he studied ritual specialists known as kerei and saw how central they are to healing, ceremony, and community life.

Core Insights From Manvir Singh

At the center of the episode, Manvir Singh offers a practical three-part definition. He emphasizes these shared traits as the “beating heart” of shamanism across many settings:

- A non-ordinary state (trance, ecstasy, or another altered mode)

- Engagement with unseen beings or realities (spirits, gods, ancestors, witches, ghosts)

- Services such as healing and divination

Singh also explores taboo, restriction, and “otherness.” He explains how shamans often cultivate social and psychological distance through initiations, deprivation, and visible markers. This helps communities experience the practitioner as different in kind, which increases credibility when the practitioner claims access to hidden forces.

Later Discussion and Takeaways With Manvir Singh

Later, Manvir Singh challenges common psychedelic narratives that treat psychedelics as the universal engine of religion or shamanism. He notes that many shamanic traditions do not rely on psychedelics at all, and that rhythmic music, drumming, dance, and social ritual can reliably produce trance states.

He also clarifies a key mismatch in many contemporary “ayahuasca tourism” settings: in many traditional contexts, the specialist takes the substance to work on behalf of the patient, rather than turning the participant into the primary visionary practitioner.

Practical takeaways for the psychedelic field include:

- Use definitions that fit cross-cultural evidence, not marketing language.

- Avoid assuming psychedelics are required for mystical experience.

- Notice how authority gets built through ritual, training, and otherness, not only through pharmacology.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is Manvir Singh a shaman?

No. Manvir Singh is an anthropologist who studies shamanism and wrote a book analyzing it cross-culturally.

What definition of shamanism does Manvir Singh use?

Manvir Singh emphasizes three shared traits: non-ordinary states, engagement with unseen realities, and services like healing or divination.

Does Manvir Singh link shamanism to psychedelics?

Manvir Singh argues the link is often overstated. Many shamanic traditions use music, dance, and ritual instead of psychedelics.

Why does Manvir Singh call shamanism a timeless religion?

Manvir Singh argues shamanism repeatedly reemerges because it provides compelling tools for dealing with uncertainty, illness, and unseen forces.

What does Manvir Singh say about “authentic” shamanism today?

Manvir Singh suggests shamanism is dynamic and adaptive. He cautions against rigid purity tests that ignore how traditions evolve through contact and remixing.

Links

Shamanism: The Timeless Religion

Manvir’s UC Davis Profile

Transcript

Joe Moore: Hello everybody. Welcome back to Psychedelics. Today. Today on the show we have Man Veer Singh, author of the book Shamanism, the Timeless Religion that came out earlier this year. How are you doing today, man? Veer.

Manvir Singh: I’m doing really well. Yeah. Thanks Joe. Thanks for having me.

Joe Moore: Absolutely. This is, um, it’s an exciting book to discuss with you and, um, excited to, um, you know, dig in and get in some fun nuance and, um, hopefully help folks in this psychedelic ecosystem understand shamanism as a, as a term and as a thing a little bit better.

Joe Moore: Um. You know, I, I think, uh, let’s just take a moment. Can you, can you explain like what high level is your, is your book and then I have like one or two questions.

Manvir Singh: Yeah, for sure. So the big thesis of the book is that shamanism is not a tradition that is confined to like remote or far off or archaic societies.

Manvir Singh: Shamanism really, uh, like [00:01:00] in the popular discourse carries this like primi vista imagery and the, the argument is that shamanism is m much more timeless, much more perennial. That it, yes, it, it would probably characterize very early religion. Um, but it manifests in the world around us today. And I think it will perennially reemerge that it is a hyper compelling means of dealing with uncertainty that humans just recreate over and over in myriad forms.

Joe Moore: Yeah, I love that. I can’t wait to get into it more. And, you know, with the, the popular narrative, um, in, in psychedelics is don’t call yourself a shaman. But, you know, then we have to like, understand what, what are we actually saying? ’cause this isn’t like an Amazonian term or a Mexican term. This is like a Russian term, like deep Siberian term that kind of, I don’t, I don’t know who the first anthropologists are, but you, you probably studied that a little bit, but you, we were seeing characteristics like soul flight, things that looked like magic.

Joe Moore: Um, are there kind of like classic categories of what is shamanism? Like, what are the features of it?

Manvir Singh: Yeah, so I mean, that [00:02:00] is like an incredibly debated thing, I think.

Joe Moore: Mm-hmm.

Manvir Singh: The image that is very popular is this one developed by this Romanian historian, MEChA Ade, who wrote this book, it came out in English, I think in 1964, shamanism, archaic Techniques of Ecstasy.

Manvir Singh: And he argued that shamanism has this paradigmatic form in Siberia and then it exists in all these other places. And the key. Features for him were soul journeying. This idea that your soul leaves your body a tripartite cosmology. So there’s an upper world, there’s a lower world. Your soul goes into these different like worlds to engage with God’s spirits, whatever.

Manvir Singh: Um, and then he saw key features like fire flight. Um, but the, the tricky thing about Eliade that we now recognize is that his scheme. Doesn’t apply cross-culturally, let alone to Siberia. Um, I mean, even if you look at the groups from where shaman, the word shaman comes from, they understood these ecstatic states in [00:03:00] much more kind of diverse and fluid ways.

Manvir Singh: They understood, yes, sometimes soul journeying, but also possession, um, sometimes understanding that like a spirit is next to you and you’re speaking to them. Um, and so the, the definition that I prefer, which I think, um, is, is more justifiable is, is on the basis of three traits. First, some kind of non-ordinary state.

Manvir Singh: So the specialist enters, it’s been called trance or ecstasy, altered states of consciousness, but some state, some behavioral or psychological state that is formed from foreign, from normal human functioning. Two, engagement with unseen beings or realities. Gods ghosts, witches ancestors. And then three, um, services like healing and divination.

Manvir Singh: Um, and I think, you know, when we look to the various traditions that have been called Shamanic, Amazonian shamanism, Korean shamanism, what you see across Siberia in Indonesia, it, it, it, like, if you wanna find out what is [00:04:00] common among the things that, that seem to people to be shamonic, I, I think those are the only three that they, that they all really fundamentally share.

Manvir Singh: But I think they’re really important.

Joe Moore: So non-ordinary states services and then unseen some sort of interaction with the unseen world.

Manvir Singh: Yes, yes. And then you have a lot of things that are often associated with that dramatic initiations music. But I think of these three as kind of the beating heart, the core of shamanism.

Joe Moore: Yeah. Right. ’cause you know, sometimes people, people fall into it. Um, that’s really interesting. Um, cool. So let’s rewind the tape. Um, how did you end up studying anthropology and then picking something like shamanism to dig into?

Manvir Singh: Yeah, how did I end up in anthropology? So I actually, I used, I am and grew up like a big animal nerd and a big mythology nerd.

Manvir Singh: Um, and in college, um, really shifted into studying animal behavior and [00:05:00] slowly was like excited about using this, like very rigorous. Framework that I had learned to study animals, especially like evolutionary theory, was excited to, to use that to study human behavior. And everything I found like puzzling and interesting and intriguing about humans, myth, magic, morality, um, religion.

Manvir Singh: And so in short, you know, I started my PhD and I decided I wanted to do field work. Then I wanted to like go to a place live with a community, um, and really study their culture in depth. And I was very interested in indigenous religion and indigenous law and justice. And I ended up deciding just for that first summer to go visit a community called the Min.

Manvir Singh: Um, these au people, they live off the west coast of Sumatra. So this is, there’s an island chain, it’s called the au Archipelago. Some of your listeners might know it as, um, like a, a really great surf spot. It’s like one of the best spots in the world to surf because it’s all the way on the edge of [00:06:00] the Indian Ocean.

Manvir Singh: So you have these swells that build up and then break on the island chain. But anyway, um, in addition to being an amazing spot for, for surfing, it, it’s the home of these indigenous people, the au Um, and I arrived there and before going there I knew that they had what people would sometimes describe as shamanism.

Manvir Singh: So like if you Google Mentali people, you’ll see pictures of, you know, people in loin clots. And you’ll sometimes these see these images of, of specific individuals whose bodies are tattooed. So I, so I had some association, like I knew there was, there was something shamanic there and, and I think like a lot of people, I had this.

Manvir Singh: Just general intrigue in the, in the term shamanism and the idea. Exactly. So these are, these are some aui people and all of these are actually re, or, or these are shamans? Um, I’m pretty sure. I think I know, I know at least one of these guys. Oh, wow. Um, but so I arrive in Aui and. Immediately on my first day, I, I actually, I meet someone, and I think [00:07:00] he was the, the second guy from the left over there.

Manvir Singh: Um, I meet him within a couple of hours. I talk about it in the book. I like, just end up in this situation. Um, but, but pretty quickly, I see how important these figures are in Mentali society. These individuals called re and they’re really salient, they’re really striking. Um, first they’re just like super visually striking and you could see that there, their bodies are tattooed.

Manvir Singh: They still wear loin cloths. You know, the au have adopted clothes, but they still wear loin cloths. They grow out their hair. Um, during ceremonies, they dress their bodies in turmeric, so they rub their bodies. So they’re all yellow. They put on leaves, they put on bells. Um, so they’re very visually striking, but then they’re also like really important social pillars.

Manvir Singh: They’re at like the nexus of religious life, of medicinal life, of political life, of ritual life. Um. And I was just like very intrigued. Like I would see from afar there, there would be these shamanic healing ceremonies. You would hear bells. Um, I would see children kind of pretending to be shamans, doing shaman [00:08:00] dances.

Manvir Singh: We would stay with, with these shamans, they’re called re and sometimes at night they would sing, um, they would sing their, their shaman songs and their incredibly beautiful and kind of haunting. Uh, they’re like, sometimes they’re, they’re usually songs to communicate with souls and spirits. Um, and so, so that first summer, it was two months and, and I just had like a glimpse of this tradition, but I was incredibly, I.

Manvir Singh: Enchanted and fascinated and like wanted to learn more. And I came back. I was, I was doing a PhD at Harvard, so I came back for my second year and that’s when I read this book by Eliade, this Romanian historian. And then I realized that, you know, there’s this incredible literature, this deep anthropological history, and that what a lot of what I found really intriguing in striking and evocative with the AU actually has these really curious echoes and parallels outside of it.

Manvir Singh: And then I came to, to really study it more in depth and, and, you know, now that was a decade ago and I still, you know, I’ve spent more than like 14 months at this point [00:09:00] with the au I’ve lived with shamans, I’ve done a lot of research there. Um, but then I’ve also done research in other places in the Orko.

Manvir Singh: So, so that summer really kind of jumpstarted this interest. Oh,

Joe Moore: thanks for sharing that. Um, and I’m glad to know that you, you kind of got that much immersion with a culture like that that’s like really fascinating. Just wanna show people the cover of your book here. Um, who, who published this

Manvir Singh: one? This is kno.

Manvir Singh: So it’s a, it’s a part of Penguin Penguin Random House.

Joe Moore: Yeah. Um, it’s gorgeous. Thanks. So, um, and then, you know, I, I imagine things kind of took a life of their own to some degree, where you’re like, what is this? And how do I kind of do some sort of cross-cultural analysis and. What is this thing, shamanism?

Joe Moore: Is that, is that kind of how it went for you?

Manvir Singh: For sure, yeah. I mean, immediately, even that first summer I was like, you know, so I grew up in New Jersey. [00:10:00] My family is from, from India, but I’m very, you know, western in a lot of my worldviews. And so I’m looking for like an analogy. How do I understand these figures?

Manvir Singh: Are they like doctors? Are they like priests? Um, and I came back and I was reading up more on them and, and something that really intrigued me was like the, the taboos that the que observe. So the, the que are really, uh. Um, respected as sources of ritual knowledge and taboo knowledge and, and religion. And yet the religious system seems to really disadvantage them.

Manvir Singh: They have all of these taboos. They can have sex a lot of the time. They can’t eat a lot of the best foods, eels, certain monkeys, certain fish. Um, and in all honesty, I was just like, why? Like incredibly intrigued by this. Why is it that these individuals seem to have so much power and prestige and influence and yet the system that they can influence?

Manvir Singh: I mean, I have kind of a, uh, [00:11:00] um, you know, I think humans are self interested. I think they’re great, but I think like a lot of humans, if they had control, they would, they would use it to, to. Benefit themselves. Um, and so I, I really started to study the taboo in depth. Mm. And it was through studying the taboo that I came to understand something really fundamental about Mente shamanism, but also shamanism around the world, which is how fundamental otherness is.

Manvir Singh: Um, and so studying the taboos and studying as the

Joe Moore: shaman being other,

Manvir Singh: yeah, the shaman being other. And so like now how I understand a lot of shamanism is the cultivation. Of otherness. And I think about that happening on two stages. Um, so first there’s kind of like the essence of the shaman transforms that you look at a lot of shamanic in shamanic initiations across cultures.

Manvir Singh: And, and what’s really central to a lot of them is this sense that this individual has become a different kind of human. We took them into the desert. We cut open their body, we put crystals inside. Um, [00:12:00] you know, they had, they died and they came back to life. Um, we have worked on their eyes with magical substances so that now they can see gods and ghosts or you know, there’s a, in, in some parts of Africa, they’ll take them into a tent and they’ll kill a dog and they’ll say, we replace their eyes with a dog’s eyes.

Manvir Singh: Um, but then in a lot of them, there’s also deprivation that to become this kind of specialist, you have to di deny yourself food. You have to deny yourself sex, you have to deny yourself social contact. And I think all of these promote this sense for the community, but also for the practitioner themselves, that they are a different kind of human and that.

Manvir Singh: And that’s kind of more credibly endowed with the powers to engage with the beyond. So that is one form of otherness. And then I think about the other form of otherness as in the moment, which is the ecstasy, the the altered state. Um, and as an example, you might come to me and you might say, or I might come to you and I say, Joe, I know that um, you really want rain lately, and I can talk to some rain goddess, you would say like.

Manvir Singh: Here’s a regular human, like [00:13:00] what makes you special? And yes, you know, maybe I had died and come back to life. Maybe I have a new skeleton. And that might promote some sense of credibility. Um, but if in the moment, you know, you can imagine two scenarios. One, I’m like rain goddess. Rain goddess, like come and change the reign.

Manvir Singh: And then another where I lose consciousness and I see a rain goddess and my mouth is frothing and I forget the moment afterwards. You know, I think there’s something so experientially powerful, both for the community and for the practitioner of the altered state as a demonstration that this person is doing something normal.

Manvir Singh: Humans cannot. And so that really, uh, through just like starting to think about taboos, I really came to understand otherness as this really fundamental thing for what the shamans are, are cultivating both in the moment and essentially, do you know what I mean?

Joe Moore: So, right. They need to be something, they need to present as something useful.

Joe Moore: Special maybe, [00:14:00] um, in order that they can deploy these services that they’re offering. Right. And, um, religious or otherwise, it sounds like. And, um, the otherness, the taboo isn’t necess the taboos and like the, i, I guess restrictions on behaviors and diets and whatnot is like a thing that can elevate that.

Joe Moore: Yeah. Like one way I’ve seen it worldwide is, is kind of like, these spirits aren’t gonna interact with us in the ways we want unless we’re ritually pure enough in these ways. Is that part of it, or is that different, or, um, yeah,

Manvir Singh: yeah. Well, so I think that intuition manifests in different ways. So, I mean, in menti, this is maybe a, this might seem a like a slightly different example, but if you wanna practice really.

Manvir Singh: Like malicious magic, you know, I want to attack someone. There’s a sense that I have to deprive myself food and sex for several days, um, to, to almost to like force the spirits [00:15:00] to work for me. Um, that if, you know, if someone hurt me, then I can much more easily use black magic, but if I really want to do it more intensely.

Manvir Singh: Um, but I think there’s also this sense. So, so, um, there’s often this sense of like, and you see this like in a, in, um, Christian stories about asceticism in the desert, that through denying yourself and going to the wilderness, you can, you know, by going to the edge, you can, you can become something different and, and align yourself more with, with the supernatural world.

Manvir Singh: Um

Manvir Singh: mm-hmm.

Joe Moore: Mm-hmm.

Manvir Singh: And again, I think of, I think of, of the self denial as just one of many pillars. Or many kind of mechanisms by which shamans cultivate otherness, both in, in the community’s eyes and their own.

Joe Moore: And we can see this, I guess in like the cultural frame too, where cultures actually deploy certain taboos in order to create that [00:16:00] otherness from other cultures.

Joe Moore: And, um, like, this is us, this is our taboos, this is what we do. Um. Yeah, I remember reading about taboos in my undergrad and like, um, how, like when, when you encounter those things in your world, like definitely investigate and like what is that? Like why, why shouldn’t I do this? Like, is it actually harmful or is it made up, or what is it?

Manvir Singh: Yeah, yeah. Yeah. I mean, there’s a whole discourse. I mean like, maybe this is slightly tangential, but the ment are coming into contact with Abrahamic religions. Mm-hmm. And like Islam is coming in fast and hard and there’s a, a big discourse about like, what is the deal with the pig taboo? Um, and people will say things like, well, a shaman cannot eat eel because if a shaman eats an eel, they will die.

Manvir Singh: Um, but all of us can eat pig. Like why is the pig taboo such a big deal? Um, yeah. Yeah. I mean, I think taboo has big social weight, but I think it also, like, it’s something people have to often contend with.

Joe Moore: Um, I [00:17:00] love that example of the eel, the, you know, perfect shaman logic, right? It’s like, um. Exactly that.

Joe Moore: If we don’t, we don’t have like, because it’s like, um, it’s not exactly like causal. It’s like, it’s, it’s neurotoxic. Your brain’s gonna go ill, it’s like, you know, there’s, there’s like a lot behind that. And I see this in kind of like shamanic storytelling and logic in the Amazon. Yeah. And elsewhere too.

Manvir Singh: Yeah. I mean, yeah. So the in min, the, the, there’s, they’re contrasted with normal humans who are called simha. And simha means, it’s also a, a word that refers to food that has not yet been cooked, like raw food or fruit that is, uh, not yet ripe. So it has this implication of being immature, of not yet developing.

Manvir Singh: Um, and so there’s this sense that queda are kind of matured, cooked individuals, but in cooking them, in maturing them, um, their essence has changed such that they can eat what are called, um, uh. [00:18:00] Iba mata, like evil food, bad food, rotten food. Um, and these, it’s more kind of on a spiritual sense. So eel is one of them.

Manvir Singh: Another one is the white kobu monkey. So on ment Ment is really cool, and so far it has a lot of primates that you find nowhere else. And one of them is white and associated with ghosts. And re shamans can’t eat that. They can’t eat. Flounders, flounders are very weird fish. They’re, they’re actually in Vento, they’re called like, uh, cut in half fish.

Manvir Singh: Um, yeah, so, so a lot of the things they can’t eat are these things that are kind of like psychologically potent. They also can’t eat Gibbons. Um, and then there’s, there’s a, there are a couple that still puzzle me. They can’t eat like a certain kind of squirrel, which is e everything else is like, so kind of psychologically and spiritually potent eels, white monkeys, the gibbons, and then the squirrel kind of intrigues me.

Joe Moore: Um, and you haven’t been able to uncover like what their kind of story is around that?

Manvir Singh: I mean, in the moment I’m forgetting, I’m wondering if they’ll say like, the squirrels call [00:19:00] sounds like maybe it’s like a summon or a signal that someone’s dying, but I, I, it’s been a long time since I’ve interviewed people about that.

Manvir Singh: Yeah.

Joe Moore: And did you get to encounter things like possession in their traditions? Like did they, that that’s a thing and they, and similarly, like a spirit right next to ’em talking or like a sort of donations? Yeah.

Manvir Singh: Yeah. So they, they’ll, they, there are many ways in which the Cade interact with spirits. The, the.

Manvir Singh: Kind of paradigmatic or quintessential practice or, or treatment is called lare. And so this is when they’ll put, they’ll cover their bodies in turmeric. They’ll, um, and then they’ll go on a dance floor, and then someone will produce music typically on reptile skin drums. So like a Python skin drum or a monitor, skin monitor, lizard skin drum.

Manvir Singh: There would be a, a drumming, you know, it has a particular beat.[00:20:00]

Manvir Singh: Um, and then the re these shamans will go on the dance floor and then they will start tapping their feet. So they’re adding a second, uh, layer of rhythm. Um. And then they will dance and um, and they’ll have feathers, they’ll have beads, they’ll have this turmeric and all of that is understood to be very, very beautiful for the spirits, uh, for people’s souls and for good spirits.

Manvir Singh: And then there’s a sense, there’s an understanding that these souls and spirits are flooding the dance floor. Um mm-hmm. And then you’ll start to see pat like observers falling into trance. Often women will, will then start entering trance. Um, and the, the trance the women enter is, is interesting. It’s kind of like an enduring long trance.

Manvir Singh: They might chant and, and go back and forth, but then this, the shamans will start to enter trance. Um, it’s called gobo. And, um, I’ve had different, this kind of comes back to the, the different, the fluid ways in which people describe. Trance. So some people will describe it. I’ve had it described to me as possession, but I’ve also had it described as [00:21:00] like, the spirits are near you and their energy is kind of coming into contact with you.

Manvir Singh: They have a word bajo. Um, so their bajo is, is pushing you into this state. Um, but then, yeah, they’ll, they’ll start dancing. And then one by one, several of them will fall into trance, and that’s a sign that the spirits are there. And then after a while, the dance will kind of fall apart because a number of them have fallen into trans People have to take care of them.

Manvir Singh: They’ll slowly be pulled out of trance, and then they’ll, they’ll dance again. They’ll fall into trance, and that’ll happen over and over and over. Um, and it’s, it’s understood to be very curative and therapeutic. This is often in the context of a healing. Um, and so the really important thing, you know, connecting this with psychedelics was that with the menti trance is induced totally by dancing and drumming.

Manvir Singh: And, and rhythm. I mean, they’ll, they’ll smoke tobacco, but everyone smokes tobacco and it’s not to a degree that’s like excessive. Um, so yeah, it’s, it’s overwhelmingly induced through [00:22:00] music. Um, and what I noticed in, in leaving Aui, which is how I, I started to get into the, the whole like psychedelic discourse, is that when I would talk to people, they would just assume there, there is such a, a, a link in people’s intuitive minds between shamanism around the world and psychoactive drugs and in particular hallucinogens and psychedelics.

Manvir Singh: Um, and I started to see that a lot of the claims that I was seeing about psychedelics, and they’re linked to shamanism and they’re linked to shamanism, both historically and cross-culturally, seemed to miss the boat that they, um, that there was often a misrepresentation of, of what shamanism looks like across cultures and the, the, the history of psychedelics.

Manvir Singh: And um, and that is how I started to kind of enter this space more and more.

Joe Moore: There’s so many ways in which we can instantiate these non-ordinary states. Um, and like list is kind of endless almost. Um, [00:23:00] I think like I, is there an example of like, um, let’s say, I’m trying to think of like negative examples. So like, um, so we have like positive examples that look just like shamanism.

Joe Moore: We’ve got Shabo shamanism, we’ve got like the assorted African diaspora religions get like, you know, um, stuff all over the world that fits these kind of primary categories. But is there kind of like one that, I don’t know, hyper commercial, ayahuasca, shamanism or something like, I don’t, is there something that kinda like breaks the mold from these definitions?

Manvir Singh: Well, I mean, one thing I would say, so I guess there are, there are two things there. Um. So, so like ayahuasca shamanism, when people go and they say, you know, they go take ayahuasca and they, they take it with a specialist who gives them a psychedelic, looks nothing like shamanism, almost anywhere in the world for a couple reasons.

Manvir Singh: One, [00:24:00] I mean, the biggest thing is that overwhelmingly in shamanic traditions, including those that include psychoactive substances and in particular hallucinogens and in particular serotonergic psychedelics, it is the specialist who is consuming the substance. Um, it is like the, the intervention is often understood.

Manvir Singh: The specialist is, is, you know, maybe consuming a substance or, or a medicine to engage with some unseen reality and through that engagement, treat the patient. Um, yeah. And so, so in that way I, I guess my feeling about neo shamanism is both that, like, on the one hand, I think a lot of what people call shamanism doesn’t look like a lot of shamanism, but on the other hand.

Manvir Singh: There are a lot of neo shamans who are sometimes it sometimes said, oh, that’s not real shamanism, that like, if you go to Burning Man, you go to Shaman Dome and there are these dudes and these people, they, they call themselves Shamanist as they’re like drumming on a drum and then they’re going to the spirit world and, and treating [00:25:00] people that, that’s like not authentic shamanism.

Manvir Singh: And if anything I think that is shamanism. I think it’s a very like, peculiar form of shamanism. It’s like one that’s informed by the western academic study of shamanism and it’s like roots in itself in this like, global story. Um, but I think that is shamanic and like, who am I to say that something is authentic or is, is not.

Manvir Singh: Um, and so far as it like embodies these key features, if you know what I mean.

Joe Moore: Yeah. Like it hits those three categories quite well. I stay the hell out of that area. But, um, you know, this idea of yeah, like we’re turning the customer client into the shaman. It’s kind of interesting and, and we kind of.

Joe Moore: Clearly know that in ayahuasca shamanism, that usually the patients didn’t drink anything or drank the lightest bit. Um, and it was the shaman’s job to go into the other world. Um, yeah, yeah, yeah.

Manvir Singh: Um, I mean, and, and linked to that, just in terms of like claims that I think are, [00:26:00] are sometimes a bit misrepresentation, you find so many of these claims that, um, like cultures around the world.

Manvir Singh: Have been using serotonergic psychedelics in shamanic context for thousands of years. Um, and my understanding with the exception of, of Southern Africa, which is like very complicated and like we’re discovering new things constantly. Um, my PhD student has been going to Southern Africa to investigate, with the exception of Southern Africa.

Manvir Singh: It looks like serotonergic psychedelics have been used in traditional context only in the Americas, like the Rio Grande area, southward, so like the native range of peyote and southwards. Um, and even there a very small proportion of societies, maybe 5% of societies in the Americas we’re using serotonergic psychedelics, or at least we have evidence of that.

Manvir Singh: Um, and so, so I, I think like this deep link between psychedelics and shamanism, although I think there are like important lessons to be drawn there. And a, you know, a bunch of the [00:27:00] psychedelics that are, that are growing in popularity do have. Histories in, in shamanic context. I think it, it actually underplays the incredibly like diverse ways that humans have, have devised to tweak consciousness, if you know what I mean.

Joe Moore: Mm-hmm. Yeah. Um, that’s fascinating. That’s really fascinating. And you’re right, like, like at home, um, at home, psycho knots are hitting a lot of these categories. Um, well, there’s only three categories and sometimes people come back with divinations or weird spirit contacts, or maybe we’re gonna get rain now.

Joe Moore: Um, and that was just like the person smoking DMT on the couch in the suburbs, and it like, looks really strange, but it Yeah. That’s fascinating.

Manvir Singh: Yeah, I mean, I, I think it speaks to just like how. I mean, my, my, my, my main thought here is that there is something so psychologically compelling about those three [00:28:00] features tied together that like we live in constant uncertainty.

Manvir Singh: We live in a world of illness and, you know, uncertain weather and uncertain, uncertain economic events. Um, and we also have this feeling, this conviction often that this uncertainty is, is linked to some unseen agents and some unseen reality. Um, and so what way is more compelling to humans of engaging with that unseen reality than to like, put yourself in a different state?

Manvir Singh: Um, I, and I, I think it’s just that simple logic that, that is so attractive and so compelling that, that leads shamanism to reemerge so easily and so reliably. Um, and, and which is the reason that I, I call it a timeless tradition, I think like. More than, um, a lot of the institutionalized religions, they will emerge, they will fall.

Manvir Singh: But the incredible like psychological gravity and pull of the ecstatic as a way to engage with the beyond, I think is a perennial human tendency. [00:29:00]

Joe Moore: And I guess in terms of like the popular uses this, these days of the term shamanism, like, are you, like, you’re, you’re clearly well aware of these debates, right?

Joe Moore: People calling themselves shamans, like you’re not a real shaman. Like is it, is it helpful in popular culture to use this term? Like in terms of like, I, I have sha people lineage and I’m a shaman. Like, it feels kind of like, let’s pull from Siberia and that makes it a little awkward. But also it’s the term of art.

Joe Moore: These days, I guess.

Manvir Singh: Yeah. Yeah. I mean, this is something I even struggled with in writing this book. Like I wanna describe a cross-cultural phenomenon, the power of ecstasy or the ecstatic or the non-ordinary, as a way to engage with the beyond and the fact that it’s so often specialists, do I use the, the term shaman?

Manvir Singh: And I think there are, there are arguments in favor and against, um, in favor is the fact that like, this is the term that’s so often associated with this practice. Um, and, you know, do I wanna just devise some new term like [00:30:00] tram, trans practitioner or something? Um, on the other hand, of course, like the pushback I often get is, and I can go over some of it, like you said, this is a term that is often associated with Siberia.

Manvir Singh: It spread into Western European languages from, um, ic, from a Siberian language. Um, and it also has so much baggage. It has, you know, the associations that MEChA Ade put on it of Soul Journeying and these different journey, uh, different realms. It has a lot of Primi Vista imagery and primi Vista associations.

Manvir Singh: Um, but I, I think both of those criticisms are a bit complicated. On the first, on the one hand, yes, it entered. Like European languages from Siberia, but it may have entered Siberia from Sanskrit. Um, and it continued, it has clearly continued to evolve since entering Western European languages. So I don’t, I, I’m, I don’t think it makes sense to treat, you know, whatever, 1600 as the, the authentic [00:31:00] snapshot of the word.

Manvir Singh: That what it referred to in that year is, is how we should use that term. I think like all concepts, it’s evolving. I mean, we’ve, we’re even using the word taboo in this conversation. Taboo is a Polynesian word. Um, but it has come to have a cross-cultural meaning beyond that. Um, and then towards this other point that Shaman has all of these complicated associations.

Manvir Singh: I mean, a part of my goal with the book was to show that, um, that this isn’t, like I said, something that is like necessarily only archaic or Siberian or esoteric or remote, but instead something like timeless and perennial. So one of my goal was to. Try to get it beyond this, this imagery. And, and, um, I mean, I I, I did that also by, by like saying some things that, that some people have really pushed against.

Manvir Singh: I argue that like a lot of the Hebrew prophets were shamans as far as we can tell, that like some Pentecostal pastors are shamans, um, that like trans [00:32:00] channelers are, are shamans that you might find in the streets of LA and that the neo shamans that you see at Burning Man, for example, or that I used to visit in the Cambridge Shamanic Circle in the Quaker Lodge outside Harvard are shamans because all of these are, are exhibiting these, these really fundamental traits that we find over and over and over the non-ordinary states, the engagement with the unseen and services like healing and divination.

Joe Moore: Hmm.

Joe Moore: Yeah. I love that. And, and I was thinking about that, like contemporary evangelical Christianity is like, you know, especially like the Pentecostal flavor, it can look very shamonic. Um,

Manvir Singh: for sure. For sure. And like, um. Yeah. And, and it there this impulse to say that is not shamanism or, or as soon as it’s applied to Christianity, it stops being shamanism.

Manvir Singh: I don’t think it’s like a, a valid one. I mean, if you saw that practice, you know, if that practice was observed among some different religion in Korea where you have, you know, ritual leaders, for example, who [00:33:00] are talking to sky gods and entering these non-ordinary states and speaking in tongues and healing people, people would much more easily call that shamanism.

Manvir Singh: I think just because it has a particular religious pedigree in history, people are a lot more apprehensive. Um, and I don’t think that’s justifiable. I think like if you’re gonna call a practice in Korea, in Siberia, in the Amazon, in Indonesia, shamanism, then you should let it describe whatever it’s describing everywhere it, uh, recurs,

Joe Moore: right?

Joe Moore: If we’re, if we’re gonna be consistent and intellectually honest and, um, yeah. So. I, I love that framing and, uh, assume you kind of saw Rick Strassman’s book, what was it? DMT and the Soul of Prophecy, that kind of framed psychedelic use and prophecy in an interesting way, um, as part of the Abrahamic tradition.

Manvir Singh: Oh, interesting. No, I haven’t, I haven’t read it.

Joe Moore: Yeah, I didn’t love it. But, uh, you know, I think it was an interesting take to say like the, so the, [00:34:00] the core of like, Abrahamic faiths came from prophecy, like obviously, and then psychedelics as kind of prophetic agents in some, in some cases. And I find, I find that interesting.

Joe Moore: Um, for sure. I mean, you have the speculations around like huffing a ship smoke and maybe DMT and whatever else is going on there, but you know, no. So the

Manvir Singh: argument is that like early Hebrew prophets are using psychedelics.

Joe Moore: Right, right. And, and that, that’s very similar to prophecy as they understand it in the, in the scripture, I guess.

Manvir Singh: Yeah. Well, I, so yeah. I mean, I think if you look at the scripture, what they’re, the way that prophecy is often described is very paradigmatically, shamanic. It’s like, you know, they’re behaving in these non-ordinary ways. They’re, in some instances it even sounds like they’re going on soul journeys. If we wanna invoke iata, you know, the hand of the Lord is on my head and I’m carried to the valley.

Manvir Singh: Um, or it’s, it’s often associated with music. And [00:35:00] divination is what prophecy is. It’s, it’s saying, you know, sharing opaque information from a divine source. Um, but it’s interesting, this, this thing that you just described where it’s like, okay, we see all of these behaviors that it seems like they probably come from, or there’s a good reason to think that that, that is related to a serotonergic.

Manvir Singh: Psychedelic is, is the kind of. Honestly, like, I don’t know the right word to describe this or the right way to describe this, and I don’t mean this in a mean way, but I think there’s almost a, a lack of an imagination or a lack of an appreciation for just all the ways that people have have induced the non-ordinary and the mystical.

Manvir Singh: Um, something I’ve been thinking a lot about lately has been soma. You know, there’s this big mystery supposedly about what Soma is, and there’s a lot of claims that Soma was a psychedelic. Um, but archeologically and ethnographically, it really seems that Soma was a stimulant. It was e fedra. [00:36:00] Um, and I think in many cultures, people have used stimulants in, in mystical states, and I think we just as a, as a society in the West have kind of forgotten that like s.

Manvir Singh: The mystical does not have to be psychedelic and hallucinogenic that, um, an incredibly diverse ways of tweaking consciousness have been understood to be mystical. I mean, coffee is often understood to be mystical. Alcohol is in some contexts associated with shamanism. Tobacco is associated with shamanism.

Manvir Singh: There’s just this deep fixation on psychedelics and the hallucinogenic as the gateway to the ecstatic, which I, I think really underplays, um, what the mystical can feel like.

Joe Moore: Absolutely. Yeah. A few things here, like, uh, Carl Hart kind of in hi number of his books, um, kind of discusses that opium and like a lot of Persian traditions, uh, using opium look quite mystical.

Joe Moore: And we demonize [00:37:00] the hell out of that. And I, I think there’s, there’s a certain kind of function of the psychedelic culture trying to set itself apart by ignoring certain parts of history and anthropology. And then there’s a historical figure of the, uh, psychedelic counterculture, Neil Cassidy, who is really, um, an amphetamine enthusiast.

Joe Moore: And he was, you know, a. A really important figure for people like Jerry Garcia and I think even, I think he came outta the beat generation. He’s kind of like a Jack Kerouac kind of era person, if I’m not mistaken. So there’s all sorts of interesting stuff there, and I, I forget sometimes about how impactful stimulants can be, because you know, you’re tired, you’re hanging out, slept kind of poorly.

Joe Moore: And then all of a sudden you take this superhuman thing and you can become a little bit more than you were earlier that morning. Or at least radically different.

Manvir Singh: Yeah. Yeah. I mean, you read the Rigveda, I, I could pull up passages, but like, it’s often like, he took Soma and that gave Indra the [00:38:00] power to defeat the, the serpent that gave him the power to like, pull apart the worlds.

Manvir Singh: It’s always, it’s often associated with like, incredible feats. Um, just coming back to the sense of like, it makes you feel like you can do things you, you otherwise could not.

Joe Moore: That’s, it’s like a weird, I love this. I love this. It’s like, it feels, it feels, uh, naughty. So it’s like hitting a taboo for me, which I think is fucking kind of hilarious right now.

Joe Moore: Um, wait, what do you mean? Oh, ’cause so, so like Rigveda, like the idea of Rigveda being kind of like, um, theoretically from Ephedra is fucking hilarious and amazing and like po like possibly quite true. It’s like a far more obvious thing. Yeah, I mean, it’s described

Manvir Singh: as a press plant. It’s effects are overwhelmingly like those of a stimulant if you mm-hmm.

Manvir Singh: Look at substances that have, that are emo etymologically related. So there’s HOA in related traditions. HOA is very often ephedra. Um, yeah, I mean I, if you look at the evidence for why it’s a mushroom and in particular something like [00:39:00] psilocybin mushroom, it’s incredibly thin. Um,

Joe Moore: yeah, fuck yeah, of course.

Joe Moore: Of course. And I’ve, I’ve read the, uh, the Rock Watson book it wrote to Lucas. It’s like radically speculative. I think you probably saw the academic article kinda like taking down their argument. Um, yeah, the newer one. Yeah. And what’s his name? Brian Mur rescue’s kind of like interesting attempt at an argument and like, certainly not academic, but you know, very popular.

Joe Moore: It changed a lot of minds. Um, and I’m still battling it like that. It’s not necessarily, this isn’t the real thing. This is like a great story, but it’s not like hard evidence. And, um. I wanted to like circle back to something you said earlier about, um, potential Sanskrit precursor to Shaman. Okay. Yeah. In terms of like word.

Joe Moore: Yeah. What, what do we have there?

Manvir Singh: Yeah. So, you know, my pronunciation, I, I would have to look up exactly how you pronounce it. Maybe it’s something like Reman or Strana. Um, I think it meant priest or monk, something like that. And the idea is that I think it [00:40:00] spread into Central Asia, possibly with Buddhist monks.

Manvir Singh: Um, but you know, this is like etymological reconstruction that far back gets, gets a bit, a bit shaky.

Joe Moore: Um, that makes sense. And you know, I think the idea that people didn’t travel from, you know, south to north ever, you know, seems a little flaky. Um. So I think, you know, why not? Totally, why not? I think that’s an interesting concept, um, especially with like how much culture kind of emanated from India, um, like long time ago.

Joe Moore: Um, and then, you know, circling back to Lucas here, um, I chatted with a lot of people recently about Lucas and this concept of like, we have to justify what we’re doing today by making it really old.

Manvir Singh: Yeah. Yeah.

Joe Moore: Um,

Manvir Singh: I mean, I feel like that is what I’m often pushing against and what I’m [00:41:00] partly pushing against at, at parts in this book.

Manvir Singh: Um, yeah, there’s, there’s this, so, so, uh, yeah, there’s this real sense among many psychedelics enthusiasts that to justify this or to make it appealing, we have to kind of connect it to some global psychedelic religion. Um, that it softens the edges, that it makes it less scary. Um. And, and I think that does a real disservice to our understanding of human diversity, to our understanding of, um, of shamanism, of religion, of, of human history.

Manvir Singh: Um, and at the same time, like there are, uh, there are groups that that use search anergic psychedelics apparently in traditional contexts that have been doing it for a while. And I think also by like linking modern usage, especially in like, you know, psychedelic or, uh, psychedelic assisted [00:42:00] psychotherapy by, by rooting that in this like supposedly indigenous worldview, you also blind yourselves to the really interesting or one blinds themselves to the really interesting ways in which groups do use psychedelics and all of the like, really fascinating psychopharmacology that they’ve developed.

Manvir Singh: Um, so like with. My colleague, Sandeep Nayak, who, he’s a professor at Hopkins, we’ve been going to Columbia and visiting some of these groups that use ypo. And you find an incredibly interesting diversity of usage. You find like mystical apprenticeships where a shaman and a non shaman will have years of, of use of ypo, where they will use it to experience the beyond and, and, and think about it and discuss it.

Manvir Singh: You have groups like the PME in Venezuela where like all adult men, every third night will take several blasts of YPO and dance. Um, you have, you know, you have groups like various two kaan groups who as a group would take ayahuasca or something similar to Ayahuasca where [00:43:00] there’s an M-A-O-M-A-O-I and and some sort of DMT.

Manvir Singh: And then they would travel to the Milky Way. And each of these groups has, has whole discourses about what are the effects, how do you manage it, um, you know, how do you manage dose with history? And yeah, I, I think like by, by continuing to exist or insist or claim that the, the particular usage that appears in trials or, or which people are trying to sell is an echo of some, some ancient and, and widespread use really misrepresents all of the like, actually useful and interesting information about indigenous use in those places where there, there does seem to be a history of psychedelics, if you know what I mean.

Manvir Singh: Hmm.

Joe Moore: Yeah, absolutely. Um hmm. Yeah, that’s fascinating. And. There’s this really interesting story I just heard yesterday. I’m, I’m kind of like interested in the, the western esoteric tradition, right? Like these, these manuscripts, Rosa Cru, magic alchemy, et cetera, and kinda like, [00:44:00] plays into a lot of things that psychedelia is sitting with these days.

Joe Moore: And there is this, um, newish book. I’m not gonna cite it or anything, but like, the idea is that this is kind of like an unbroken chain of manuscripts and ideas, you know, from ancient Greece and before. And, um, the, and the discovery was that somebody 14 hundreds, 15 hundreds, like hired a, um, a, a Jewish magician and they were kind of, this other person was kind of like a scribe and, um.

Joe Moore: Kind of a, uh, magician of their own right. And they just kinda like merged things and made like some sort of manuscript that became like the template for the next hun couple hundred years of this theme Yeah. Of manuscript. And it was like really fascinating to like hear some people who are like really deep in that tradition, really like, believed in it and cared about that kind of like unbroken chain.

Joe Moore: And they’re just like, their heart collapsed, but it’s like, you know, you’re still hitting these three categories of things like the OSCs, the services unseen world. And it’s like, you know, it’s, it’s fascinating to me and [00:45:00] it’s, I think I’m interested in that whole field because it kind of like shows that yes, there, this stuff was happening in Europe.

Joe Moore: It didn’t necessarily always have to be drugs. There could have been other things, but there could have been drugs, there could have been plants.

Manvir Singh: Yeah. Yeah. Yeah. I mean plants, I, I, I, um, I, I’m often pushing against serotonergic psychedelics because they’re talked about so much, but I, it’s definitely the case that like, plants are often involved and, and an, in an interesting ways, um.

Joe Moore: Right, like des like mandrake, there’s all sorts of like, really sketchy plants that they would use that are super dangerous. It’s not, it’s not that like they weren’t using dangerous things that weren’t serotonergic. It’s just, you know, and they could have been doing all sorts of things like fasting for 40 days plus or whatever, you know, in a monastery, there’s a lot of room for experimentation.

Manvir Singh: Yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah. For sure. For sure. Um,

Joe Moore: yeah. So, um, what were like for you, kind of the most [00:46:00] surprising things or, or challenging concepts as you were kind of working through this book?

Manvir Singh: Challenging. What do you mean challenging?

Joe Moore: Um, intellectually challenging just to piece together and or challenging for pop culture.

Manvir Singh: Well, yeah, I mean, I, I’ll tell you something that I, I’m often trying to work with. Mm-hmm. Um, so there’s something like. And just building on, on what we’re talking about. If, if we use Soma as an example, let’s say like the, the evidence suggests that Soma is not a psychedelic and is instead a stimulant, but the story of it being a psychedelic is like very rich and, and kind of beautiful and interesting.

Manvir Singh: And, and, and so something I i a challenge sometimes is like, how do you be deflationary but still in invoke or evoke wonder? Um mm-hmm. Do you know what I mean? Like, how do you say that? Like, well, in fact, only a minority of the world’s cultures have used psychedelics. But, um, but that’s like, nevertheless still interesting and [00:47:00] wondrous.

Manvir Singh: Um, because I think like so much of the discourse finds wondrousness in history and in diversity through psychedelics as a lens. Um, and, and. Trying to see wonder in that I think has been a really useful exercise. Like that is what kind of gave me an appreciation for, um, for the ways in which we no longer appreciate stimulants as, as, as ways to, to get into the divine or, or, you know, the, the larger kind of under-appreciation for the many, um, for the many like methods that people have used to, to discover non-ordinary states.

Manvir Singh: So I think that’s, that’s just like the project of being deflationary, but nevertheless finding wonder. I, I found a really kind of like useful exercise. In this kind of work. And I think that’s something that like a lot of academics have to contend with and maybe often don’t do well enough. Because I think like there’s some stories that, that, that succeed because they’re interesting and [00:48:00] cool and rich and like narratively compelling.

Manvir Singh: And I think some scholars sometimes try to push against them, but they don’t have the story to replace it with. Like, I’m thinking of Graham Hancock, like mm-hmm. In whatever corner of Twitter I’m on, as a lot of people who like grumble about how Graham Hancock really misrepresents archeology and history.

Manvir Singh: Um, but I think the people they’re talking to often don’t care about the facts. They care about the story. And so I think that the, the thing that you often have to do is like, how can you build stories, build narratives that, um, that feel as compelling and rich as the ones you’re trying to, to replace?

Joe Moore: That’s gonna be a forever problem with Graham. I don’t, I don’t, I don’t think academics can, like generally speaking, tell such a compelling story. Right. Um. So I want to kind of double up on your kind of wonder and deflation story. ’cause I, a lot of our work here at Psychedelics today is not about psychedelics, it’s about hocher breath work and things in that lineage where it’s, it’s about group and music and body.

Joe Moore: Yeah. And, [00:49:00] um, how it makes the human body a little bit more wondrous that we can do these things. Yeah. Without substance. Yeah. It’s already there. You’re the ma, like that kind of thing. I, I was saying is that you’re the magical thing. Yeah. Like how amazing is that, that you’re already magical without it?

Joe Moore: You just have to try.

Manvir Singh: Yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah. Yeah. I mean, I, I think about that. So like, and another thing I write about in the book is about like the question of how old shamanism is. Um, and so to answer that people, one of the things people look at is rock art. Um, and you know, there are these things called thi and ropes, which are like human animal hybrids.

Manvir Singh: Um, so there’s a very, I laugh ’cause

Joe Moore: of the Graham Hancock link and that’s one of his. Kind of deals that he loves to get into.

Manvir Singh: Oh, interesting. Yeah, I honestly have not read enough Grand Hancock to like even know what’s a, what’s a trigger or what’s relevant to him. Um, but, but so yeah, so, so, so I visited one of these caves where you have these theory and tropes, um, and like my honest appraisal is like, who knows [00:50:00] if that’s related to shamanism?

Manvir Singh: Um, but I think by like insisting that it is, we are kind of similar to what you’re saying, we underplay like human imagination and human creativity and like the things that hu the places human minds can go to, um, to like often, oh yeah, we need, we need, um, hallucinogens or psychedelics or plants or even trance to, to, to like think about the wondrousness and the imaginative, I, I think does a real disservice to just like humans.

Manvir Singh: Um, yeah. So, so just to say that that’s something that’s, uh. I, yeah, I mean I think that actually links to like a lot of the claims that are made about psychedelics when psych, you know, psychedelics has the origins of religion. I think also similarly does a disservice to like the human capacity for religion and the human capacity to, to feel kind of divine presence.

Joe Moore: Right. Absolutely. Like does it also like devalue music in an interesting way? Yeah, I, I think there’s a lot here. Um, yeah. Like a lot of [00:51:00] the things that humanity is expressing does become devalued. We’re saying it’s only with drugs.

Manvir Singh: Yes, yes, for sure. I mean, like the, the healing ceremonies I’ve seen in ment are so rich and evocative and like transporting, um, just the, the social presence, the, like, it’s a collaboration among so many people to create an incredibly kind of immersive healing environment.

Manvir Singh: You have people drumming, you have other people who are heating the drums. You have the shamans who are dancing, you have observers who are falling into trance. Um, and all of that is giving the, the patient, the client some sense that, that whatever source of affliction is being contended with. Um, yeah.

Manvir Singh: Yeah. And so to boil that down to a drug, I think like really ignores all of the cool ways that humans have devised to, to transport ourselves.

Joe Moore: Hmm. So people should obviously read your book, but like, if they want to go beyond their, your book and, and want to kind of understand Shamanism a little bit, you know, more deeply [00:52:00] in different ways that maybe you don’t cover, like what are, who are some authors or books you might recommend beyond yours?

Manvir Singh: Yeah. So of course I think my book is like the best or no, I, I mean, I think it’s, I think it’s a, I think it’s a great introduction. Mm-hmm. Um, but if I were to recommend like, where you should go, I would, I think I would really emphasize going straight to the ethnographies. Um, so there’s this book, boiling Energy by Mm, I believe the first name is Richard, Richard Katz, about trans healing among the Kalahari Kung.

Manvir Singh: Um, and so, you know, that’s a tradition. The k Harry Coner, uh, like hunter gatherers, former hunter gatherers who lived in like Namibian Botswana and Richard Katz did a deep study of, of just their trans healing practice, their like chapters, entire biographies of particular healers. Um, I think that’s a great book.

Manvir Singh: I think the Catalpa bo about Shamanism in Japan is a really great book, I think, um, the Fallen Sky by Davi Awa and Bruce [00:53:00] Alpert. So this is an, an, a collaboration between a Yana mama shaman and a French anthropologist. It’s like, um, an autobiography of this Yana Mama shaman. But I think that’s an incredibly powerful book, and I think the footnotes are alone, are like a great lens or perspective into the Yana Mama worldview.

Manvir Singh: Um. Yeah, I mean, is there

Joe Moore: anything around like pre Hindu shamanism, like pre kind of like whatever, like came Yeah. Like in Iranian. Right, right. Oh, that’s, that’s interesting. Yeah. That makes sense.

Manvir Singh: Well, yeah, so I mean, I have a separate like total obsession and fascination with like Proto Window European, the early Indo-European traditions.

Manvir Singh: And so there’s this great book, it’s like

Joe Moore: proto Zoroastrian kind of traditions or,

Manvir Singh: well, yeah. So it’s, it’s, so you know the Indo-European language family? Mm-hmm. So that’s like Germanic, you know, German, whatever, English, um, Norwegian. Swedish [00:54:00] Icelandic. But then all the italic languages, you know, so all the romance languages, all the Slavan Slavic languages, all the Baltic languages, but then also Iranian languages, and then also Northern European languages.

Manvir Singh: All of these come from a single language called proto Indo European that was spoken probably on the step mm-hmm. In Ukraine, north of the black. Um, and so we’ve done, you can, the story essentially is that these peoples who, these step peoples who lived north of the Black Sea had horses and were like pretty warrior ish.

Manvir Singh: Um, and then came to just like spread and conquer or, or at least, at least spread, um, throughout much of Europe, Iran, central Asia, and then Northern India. Um, and you can get like a, a, a good lens into their worldview through texts like the Rigveda or the Homeric Epics or the early Zoroastrian texts like the Avesta.

Manvir Singh: Um, that’s all to say that. So there are some really great books about the religious worldview of the Proto [00:55:00] Window Europeans, where people have like, through comparing texts like the old Zero Austrian texts and the rig via and the Homeric epics, um, you can, you can get a sense of what the mythology and religious practices of these people looked like.

Manvir Singh: And in there you can also get a, a, a, a rough sense of, of what some of the shamanism looked like. Um, so a great book on that is Martin West’s, I think it’s called Indo-European Poetry and Mythology, or Indo-European Myth, myth and Poetry, something like that. But by Martin West, that’s a pretty scholarly book.

Manvir Singh: And it’s like a lot of like, this is what the rig day says. This is what, like, you know, this passage of Homer says, this is like what, you know, this passage of this book of the Avesta says. But, but I think it’s an incredibly cool book because I think the fact that we have reconstructed this world from, you know, 5,000 years ago, um, is super, super cool.

Joe Moore: Right. Absolutely. And it’s, um, we’re I guess finally at a moment with all these ancient texts and scholarship where we can do these analyses. Um, like I [00:56:00] remember, I. I dunno why, but I was studying the Bible a bunch in my undergrad and I was like, oh, all these different kind of texts informed like this particular edition, I made it here and here and here and like, yes.

Joe Moore: You know, you could kind of like track down missing manuscripts. Um, and yeah, I, I love that kind of analysis of like there being yeah. A sort of kind of, um, horticulture that informed all these other things that are still around today. And yeah, the idea of the same thing that informed the rig data informing ho uh, rig beta informing Homer is really interesting to me.

Manvir Singh: Yeah. Yeah. I mean there’s, there’s good reason to think that Indra Thor, Zeus, Jupiter all partly come from the same God, from God Enos, um, a big red bearded thunder, God who drank a lot, got in a lot of fights, defeated a serpent, um, was a bit rambunctious.

Manvir Singh: Yeah, no, I think it’s super, super cool. You know, we know there was probably a dog named something like Berros who, you know, looked over the [00:57:00] underworld. There was probably a figure who stole fire from the gods and gave it to humanity. Um, yeah, it’s super cool.

Joe Moore: Wow, that’s fascinating. I’m just thinking about Zeus’s misbehavior, but also his like, kind of figure had his king like Yeah, it’s fascinating.

Manvir Singh: Yeah. Zeus is an interesting figure. Zeus and Jupiter are interesting figures ’cause they actually seem potentially like fusions of two proto Indo-European gods. There’s like Deus Pater, the, the Sky Father, Deus Patter, um, which manifests then in Zeus pater and Jupiter. Jupiter is just like a fusion of essentially sky and Father.

Manvir Singh: Um, so the sky father became fused with the thunderer God. Mm. Um, in Jupiter and in and in Zeus

Joe Moore: wild. And um, oh gosh, we could go on So many fun tangents now. But I, um, uh. Really wanting to read what Charles Ang is working on around proto, [00:58:00] I think like pro proto solar cults in, in that particular area. Um, I don’t know when that is gonna come out, but I’m, I’m hopeful that I can get him on to, to chat about that and how that might inform kind of an interesting kind of larger, I don’t know, expanding the scope of psychedelic conversations beyond drugs.

Manvir Singh: Yeah, yeah, yeah. Yeah. That sounds super cool. I did not know he’s working on that.

Joe Moore: Yeah, I, I I think that’s what he said pro. Yeah, that sounds right. It was well over a year ago, um, that he told me that. So, uh, hopefully my memory’s right. But, um, yeah, so I think the takeaways are, yeah, this, like the three things that make up this thing that are shamanism is non-ordinary states, unseen world and services like divination and, and healing.

Joe Moore: And I think that’s like. I think that’s really important for us to take away here as we get a little sometimes inflated over what is and is not shamanism and like, maybe that’s not the fight that we wanna make. Um, yeah. Yeah. I

Manvir Singh: mean there’s mm-hmm. Like [00:59:00] a, a point that I I like to make is that like all shamanic traditions are dynamic and changing and like adapting and, you know, com importing influences.

Manvir Singh: And so this idea that, like for instance, just to choose one example, Neo shamanism is like not is, is some newfangled modern form of shamanism and there’s, it’s, it contrasts with so-called traditional shamanism, I think like. Is is diluted. I mean, all shamanisms are are constantly evolving and I, that’s something I learned and recognized w working with the ment because like so much of what characterizes menta shamanism, the, the cre, uh, came in from, from contact with outsiders.

Manvir Singh: They have bells that seem to have come in from trade with the Dutch. They wear dance skirts. They covered themselves in beads. Um, all of these came in from the, from the outside world. So what looks like very traditional shamanism is actually just as like a much a product of, of globalization and, and colonialism as, as, um, as some of [01:00:00] these like so-called newer forms of shamanism.

Joe Moore: Yeah, I think, I think I heard somebody I, I respect recently saying like, all, all of like this cultural development stuff is kind of like, not all of it’s just like the most disgusting of colonialism. Like a lot of it’s just kind of natural humanity. Um, like being kind of like a, like a scavenger bird.

Joe Moore: Like let me take that. That looks good. Um. Yeah, for sure. Right. Lemme try that.

Manvir Singh: Humans are constant remixers,

Joe Moore: right? And I, I was, I was hearing recently that some of the traditions in like Brazil were taking some of the European kind of manuscripts and integrating that into their kind of like, um, traditional practice, like, you know, kind of African diaspora, tra traditional practice.

Joe Moore: It’s like fascinating to know that it’s still evolving. Um, and you know, I think that’s, that’s the thing. Everything’s just gonna keep changing and moving around. And now, now, thank you. I have kind of a good foundation for going forward. I really appreciate that.

Manvir Singh: Yeah, yeah, of course. Yeah. Thank you.

Joe Moore: [01:01:00] Yeah. Um, so where, where can folks find your book?

Manvir Singh: Yeah, so my book should hopefully be in most stores. And then you can also get it on like most web platforms, amazon bookshop.org. You can get it on Audible. Um, if you do read it, I hope you enjoy it and like. Recommend it to someone, but also to consider rating and reviewing. ’cause I increasingly really, um, recognize how important that is for just helping find readers.

Manvir Singh: But yeah, I hope, I hope people get in. I hope they enjoy it and if they do enjoy it, they should feel free to reach out to me.

Joe Moore: Hmm. I love that. All right, well, I tragically only caught a few chapters in and I wish I got through the whole thing, but soon enough. So thank you man, for being here. Um, I hope, uh, we can check in again in the future and, and good luck with the book.

Manvir Singh: Yeah, thanks a lot for having me, Joe. This was a lot of fun.