Australia’s relationship with psychedelics has taken a dramatic turn in recent years – but beneath the surface, an enduring underground movement has quietly shaped the country’s evolving psychedelic landscape.

In 2023, the country’s Therapeutic Goods Administration made a groundbreaking decision to reclassify psilocybin and MDMA under Schedule 8 (Controlled Drug) for specific therapeutic uses. This decision reflects a global shift towards recognizing the potential benefits of psychedelic-assisted therapy, particularly in treating mental health conditions like treatment-resistant depression and PTSD.

While this movement is largely focused on clinical settings, there is another, less visible layer to Australia’s psychedelic landscape: the underground.

The story of psychedelics in Australia isn’t just about modern medical breakthroughs; it’s about a rich, covert history where underground practitioners, researchers, and communities have kept the flame burning throughout decades of prohibition.

In this article, we explore the Western influence of psychedelic interest, information dissemination, and the key underground movements that have shaped Australia’s unique relationship with these substances, from the early days of prohibition to the present psychedelic resurgence.

The Underground Origins of Psychedelic Science in Australia

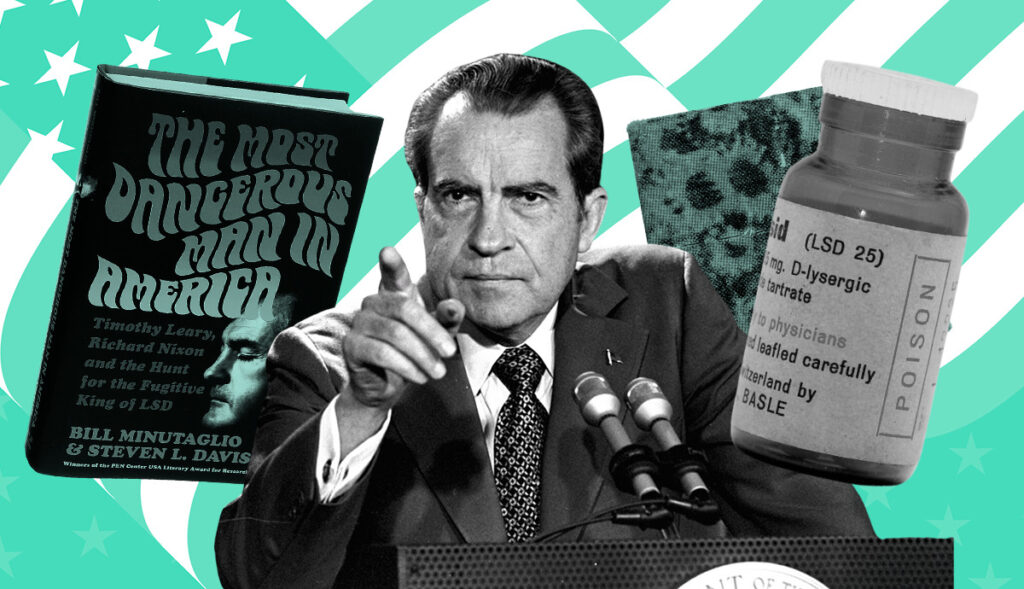

The global story of psychedelic prohibition is well-known, beginning in the late 1960s when substances like LSD and psilocybin were criminalized. Though geographically distant from the epicenter of the War on Drugs, Australia was significantly impacted by this shift. Formal psychedelic research ended in Australia, as the U.S. declared psychedelics a societal scourge.

From then, the culture of psychedelic science in Australia went underground. During the ’70s, ’80s, and then into the psychedelic renaissance of the ’90s, research around entheogens continued in an active and vibrant counterculture.

Australia’s underground science has been multidisciplinary, with chemistry, botany, mycology, anthropology, and archaeology all contributing to our understanding of these compounds. While these substances were typically used recreationally, there was an appreciation for how they could be used therapeutically; it is this therapeutic aspect that is currently driving contemporary interest.

Looking at the entire history of psychedelics that is known: the past 50 years of prohibition have been the exception rather than the rule. Only a handful of cultures exist that do not use psychoactive substances in some way, and much of our knowledge about these plants comes from traditional societies.

As we move forward into a period of time where psychedelic therapy carries a sense of legitimacy and hope, it is important not to dismiss the wealth of knowledge maintained by generations of psychedelic scientists, harm reduction educators, and underground facilitators who have passionately continued their work with these substances regardless of the legal implications.

There exist many communities of people who actively help support each other to understand themselves and how to “do the work,” not just underground practitioners but also groups of young men and women who are growing plants and mushrooms, sharing them with their friends in a community of shared knowledge, and supporting each other’s work through traumatic experiences.

Psychedelic Science Becomes Citizen Science

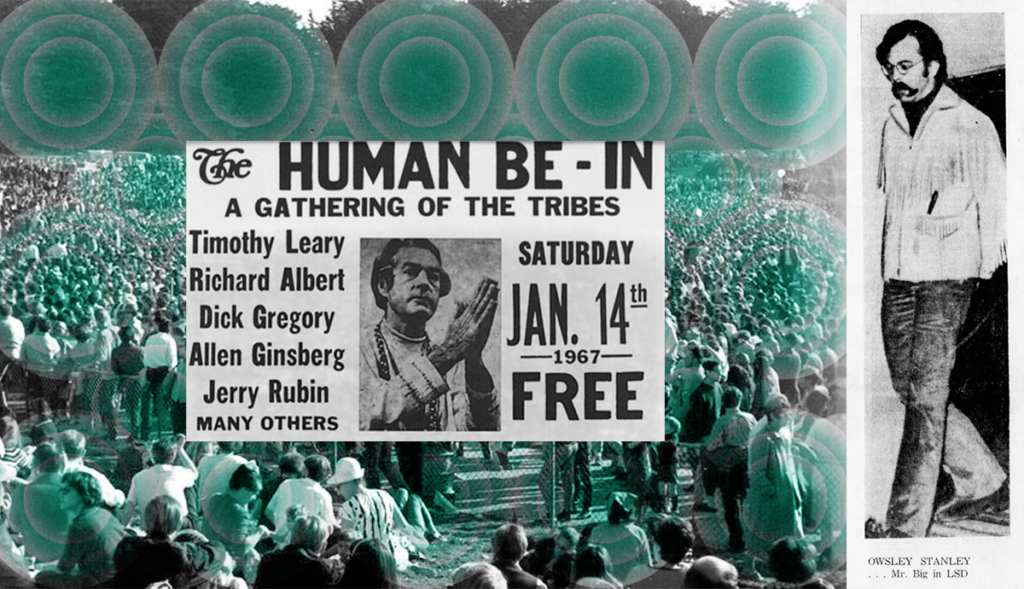

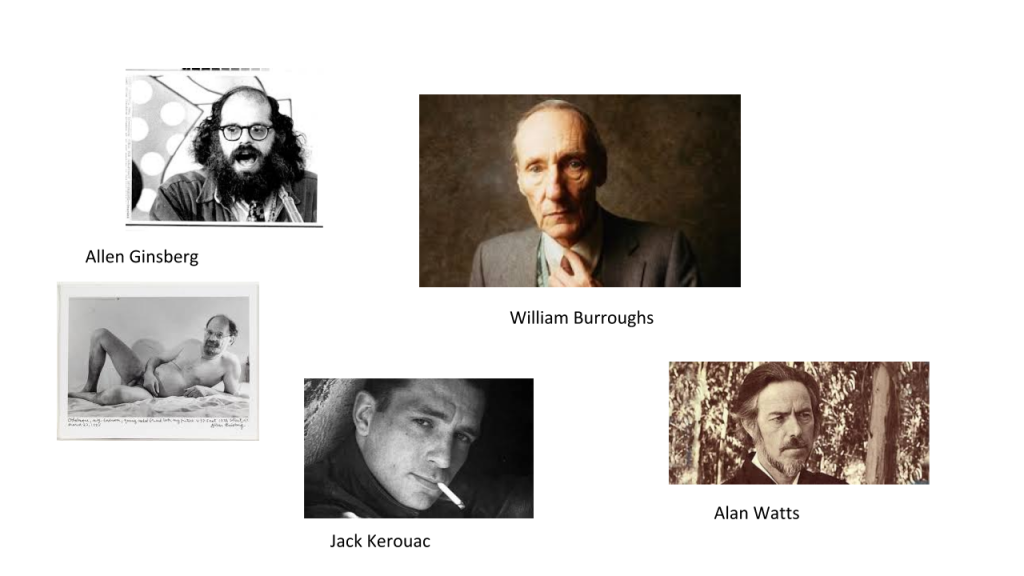

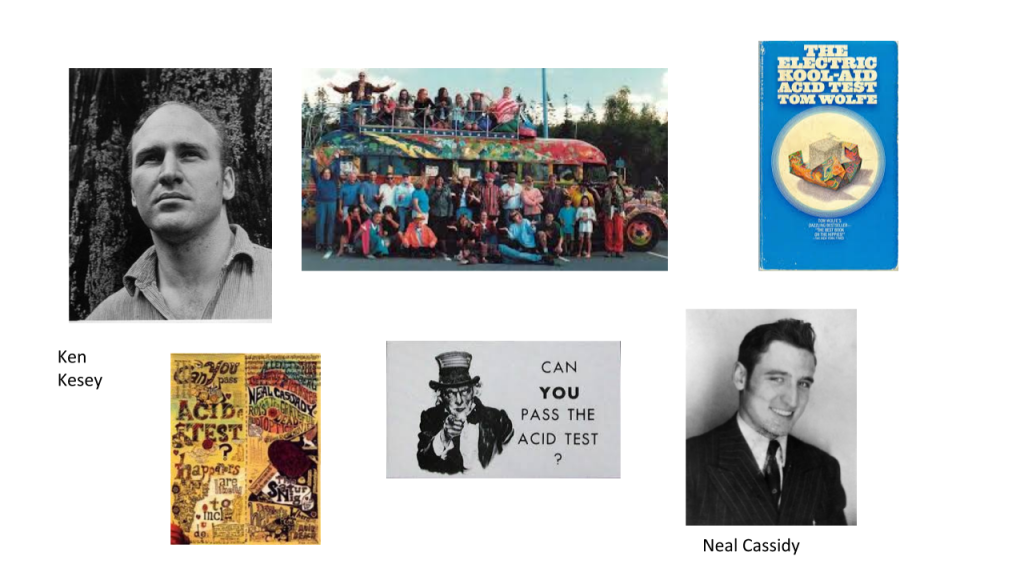

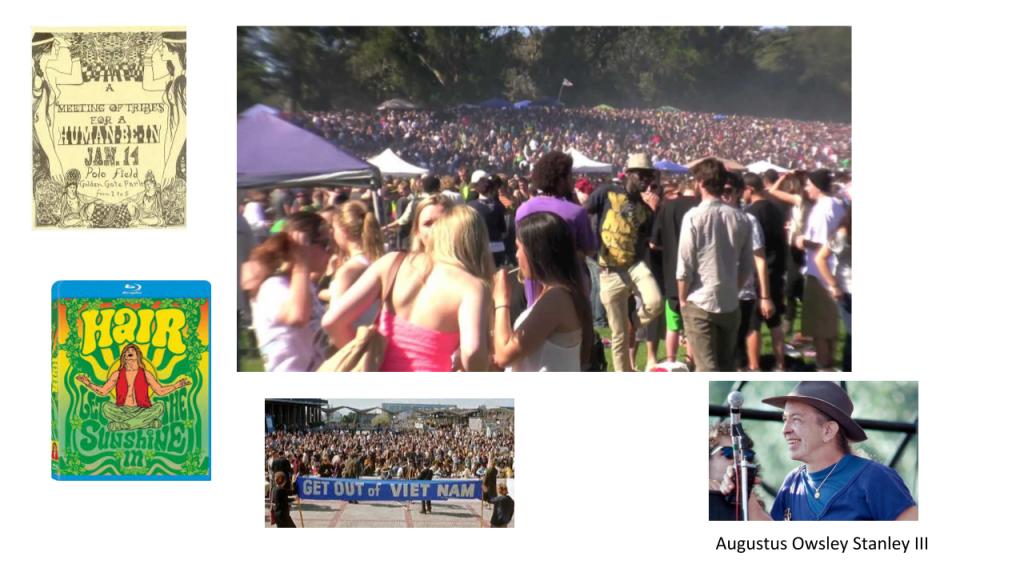

The psychedelic surge of the ’60s catalyzed a generation whose interest in psychoactive compounds could not be quashed by prohibition. Events and publications on psychedelic plants and fungi were essential to spreading awareness and cultivating a movement of citizen science in Australia and around the globe.

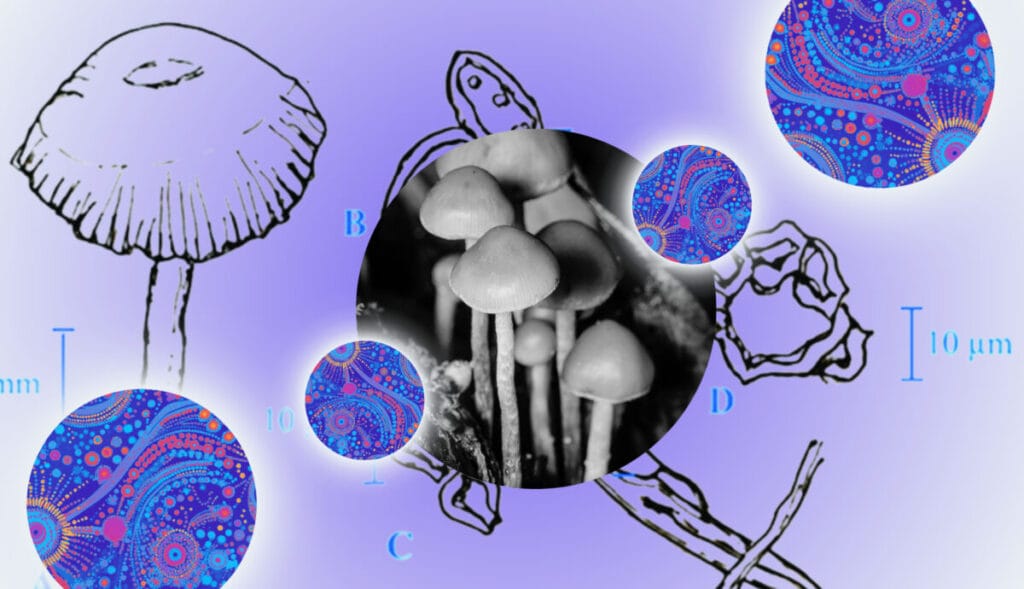

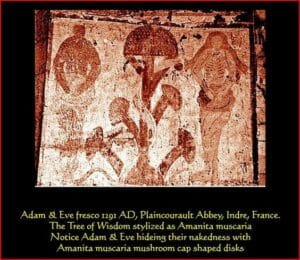

Anyone who had a copy of the famous article from Life Magazine written by Gordon Wasson had access to the beautiful and taxonomically accurate illustrations by French Mycologist Roger Heim. It was from these illustrations that many first learned how to identify the Psilocybe mushroom species in the wild.

The landmark 1967 San Francisco conference, Ethnopharmacologic Search for Psychoactive Drugs, was the first conference dedicated to conversations about psychoactive plants and fungi. The conference also published a book with numerous articles discussing many entheogens. This conference and book were seen as significant at the time and were revisited 50 years later, with another conference and second volume of the book.

The late ’60s saw the beginnings of a ‘literature underground’ that communicated a lot of the information people wanted about psychedelics. In 1969, Robert E. Brown and associates published The Psychedelic Guide to the Preparation of the Eucharist in a Few of Its Many Guises, a publication that set the bar for a sophisticated level of knowledge that circulated in underground texts for decades. The book described the cultivation of a number of entheogenic plants and the extraction and synthesis of the associated alkaloids.

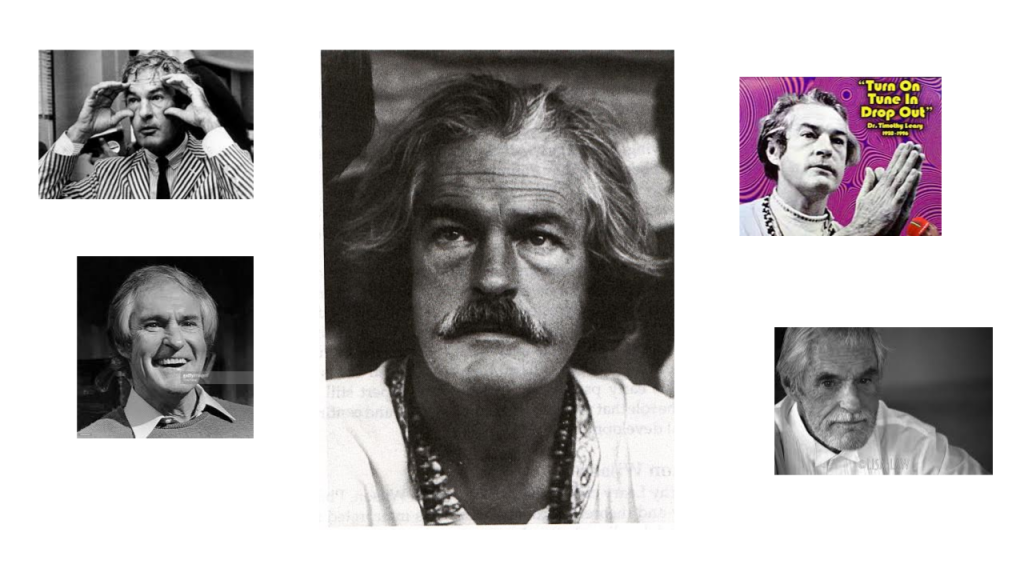

Though formal research ground to a halt around the world following prohibition, the non-clinical use of psychedelics kept going. And while underground chemists such as Bear Stanley and Nick Sand were producing large quantities of LSD, those in the movement were also investigating alternatives, particularly psilocybin-containing mushrooms.

In the following decades of underground research, two fields of study in particular significantly contributed to psychedelic science: ethnobotany and mycology.

Ethnobotany in Australia: The Planting of Many Seeds

The landmark Life Magazine story, Seeking the Magic Mushroom, sparked an interest in the traditional use of many fungi and plants. When LSD was criminalized, many began looking for alternatives.

There had been a fascination for psychoactive plants within the scientific community for hundreds of years, with the publication of many Materia Medica discussing the use of poisons and narcotics for medicinal applications.

Many of these books referred to older herbal books or medieval manuscripts. Considerable psychedelic-referencing literature was written during the early 1900s, with books and papers discussing peyote, morning glory, ergot, and, of course, fungi.

The publication of Carlos Castenada’s The Teachings of Don Juan in 1970 sparked a wider cultural fascination with psychoactive plants in Australia. A growing curiosity led many people to source some of the plants discussed, often not ethically.

Peyote especially suffered from overharvesting, making it harder for Indigenous groups to access the plants necessary for their traditional pilgrimages. Some plants, such as Datura and Brugmansia, became problematic, with people not appreciating the dangers inherent in such powerful entheogens.

Jonathan Ott’s Hallucinogenic Plants of North America and Richard Evans Schultes’ Hallucinogenic Plants (A Golden Guide) became key texts. The later book laid the groundwork for the publication of the 1979 book Plants of the Gods. The 1992 reprint rekindled the fascination in ethnobotany into the 1990s.

Finding Fungi: Mycological Exploration in Australia

Mycology has long been a key aspect of citizen psychedelic science in Australia. Mushrooms had the benefit of being free but also came with the thrill of foraging. Foragers will happily tell you how rewarding finding a large haul of mushrooms can be. While many plants take time and patience, magic mushrooms could be readily foraged or cultivated in a matter of months, but also discreetly.

The culture around the cultivation of Psilocybe cubensis “Gold Tops” or “Golden Teachers” and Psilocybe tampenensis “magic truffles” or “philosophers stones,” has been one of the significant undercurrents in psychedelic science in Australia.

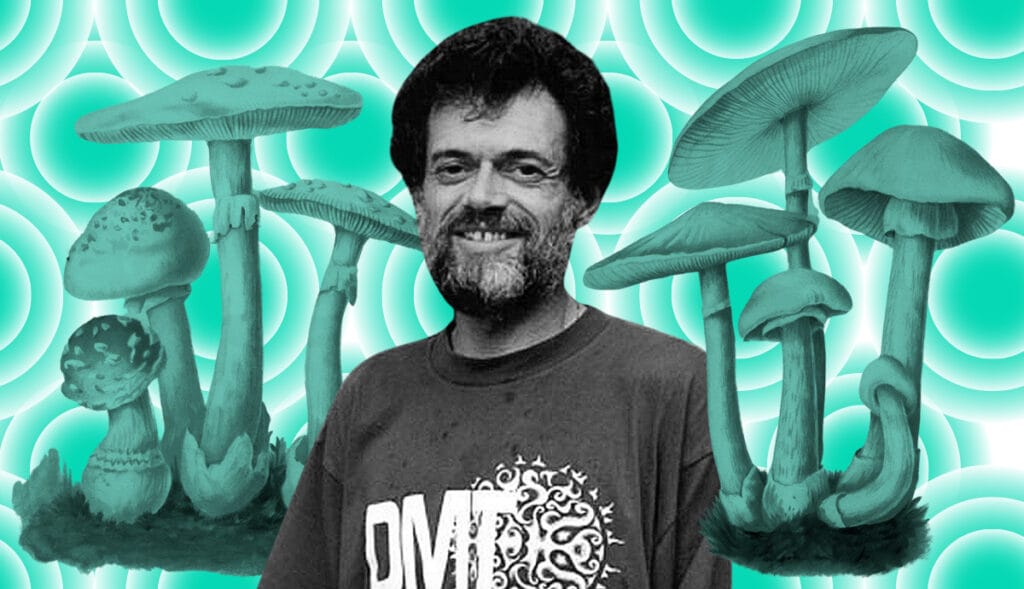

Books sought by burgeoning mycologists in Australia included Psilocybin: Magic Mushroom Grower’s Guide, How to Identify and Grow Psilocybin Mushrooms, Teonanácatl: Hallucinogenic Mushrooms of North America, and Paul Stamets’ The Mushroom Cultivator.

Readers who purchased High Times in the late ’80s and early ’90s may recall numerous advertisements selling mushroom grow kits or spore prints. The most notable of these was the PF Tek, a simple, but ingenious kit that made the cultivation of P. cubensis incredibly accessible.

In 1991, Alexander and Ann Shulgin published the legendary book PiHKaL, followed by TiHKaL in 1997. These two books were published based on the citizen science principles of keeping the science open, to use by those who are interested in diving in.

In 1997, the website, The Shroomery, launched and quickly became a significant resource for all things psilocybe and mushroom cultivation in general. Other sites that helped communicate information about psychedelics included Lyceum, EROWID, and the forums Bluelight, Mycotopia, and DMT-Nexus.

In Australia, The Corroboree (the world’s longest-running ethnobotanical online forum) and Ethnobotany-Australia were crucial sites for locals exploring psychedelics.

The Psychedelic Underground in Australia Flourishes

While the United States and Europe were the epicenters of this cultural change, Australia was not immune to their influence. Music, clothing, fashion, and lifestyle choices were a little behind their contemporaries, but a fascination with psychedelics was a big part of this dynamic.

In his 1934 book Toadstools And Mushrooms And Other: Larger Fungi of South Australia, mycologist John Burton Cleland wrote:

“Some species of toadstool give rise to a kind of intoxication. A former colleague of mine told me how ‘my parents ate once a dish of mushrooms, and as the meal progressed, they gradually became more and more hilarious, the most simple remark giving rise to peals of laughter.’”

It is thought the mushrooms were Psilocybe cubensis, picked while foraging for field mushrooms.

In 1958, mycologists Aberdeen and Jones published a paper entitled A Hallucinogenic Toadstool in the Australian Journal of Science. They were investigating Panaeolus ovatus, thought to be responsible for several accidental intoxications in Australia, but the pair concluded it was more likely P. cubensis. Aberdeen is remembered for being particularly interested in this hallucinogenic species.

“For some time, young drug users had been aware of the existence of a ‘legendary mushroom,’ but information regarding habitat, identification, and effects was lacking. It seems that the necessary information was supplied by a visiting surfer from New Zealand or the U.S.A.,” wrote J.P. McCarthy in 1971.

Locals in the small town of Nimbin in Northern New South Wales would disagree, saying: “We knew about them long before that.”

Australia is home to some particularly beautiful cactus collections, with many Trichocereus species imported during the ’50s and ’60s and allowed to grow to impressive stands. Members of cactus communities often met and swapped seeds and cuttings of various species, including peyote.

In time, many of the larger cactus collections were opened to the public. With the resurgence of interest in hallucinogenic cacti, a new generation began growing and setting up small nurseries. One of these, Urban Tribes, regarded as one of the better cacti collections in Australia, was created by Mark Camo in 1994, who was also possibly responsible for the first cutting of Banisteriopsis caapi in Australia.

Connecting the Psychedelic Dots Across the Continent

Australia is a large, mostly empty country. Psychedelics, being a fairly niche, and legally tricky interest, meant a lot of people interested in underground psychedelic science were often isolated from each other.

The Australian psychedelic underground has required a certain level of self-sufficiency, and networking, but with the introduction of electronic communication in the early ’90s, things rapidly changed.

The publication in 1994 of Cyberia: Life in the Trenches of Hyperspace introduced many to this rapidly evolving network of technically minded psychonauts. The emergence of various websites and forums within the digital landscape of the late ’90s allowed a much broader and more immediate form of interaction, education, and harm reduction around the fungi, plants, and compounds being used in Australia.

It was not unusual during the ’90s and early ’00s for small crowds of individuals to gather in the forest for ‘bush doofs’ (or raves). These gatherings became psychedelic meeting points, allowing people of like minds to connect and share knowledge. As the ’90s progressed, there was a revival of countercultural ideas, with a fascination for the Beat movement of the ’50s, alternative lifestyles, and particularly, psychedelics.

A growing interest in ethnobotany led many university students to access scientific literature and distribute knowledge on the internet. Information about the presence of DMT in Australia’s native Acacia, Acacia maidenii, was discovered in scientific literature by a student at the University of Sydney, who went on to publish extraction techniques and subsequent experiments.

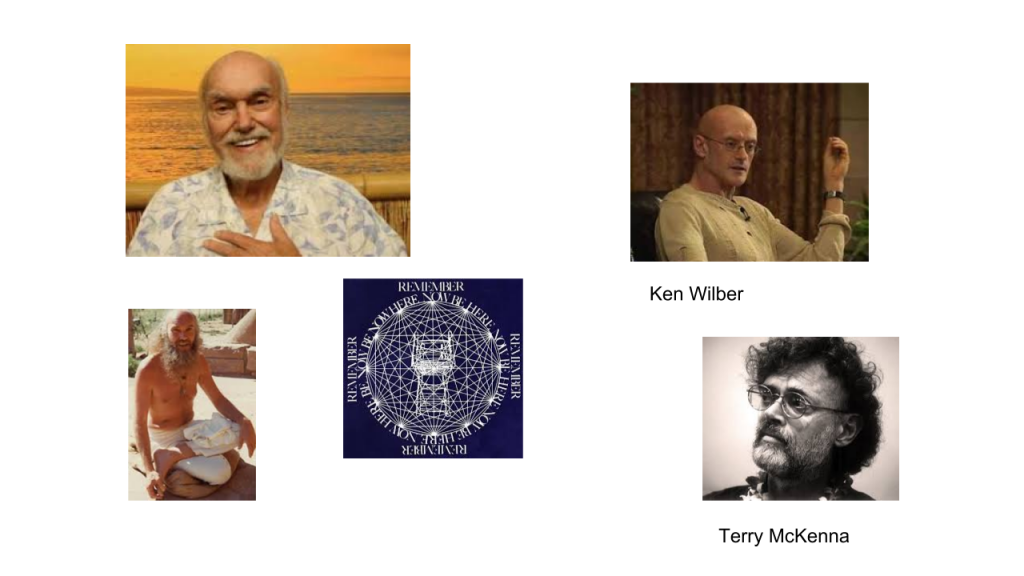

Terence McKenna visited Australia in 1997 for a speaking engagement at Beyond the Brain Club in Byron Bay. Rumor has it McKenna left a B.caapi vine cutting behind. DMT and ayahuasca were rapidly gaining popularity at the time, and McKenna’s visit led to an increased curiosity and, in time, the popularity of ayahuasca circles in Australia.

The first of many Ethnobotanica conferences was held at Wandjina Gardens in Northern New South Wales in 2001. These small gatherings inspired the formation of Entheogenesis Australis (EGA), which held its first conference in Belgrave, Victoria, in 2004.

These events allowed a multidisciplinary community of both underground and aboveground researchers, scientists, writers and more, to come together, share knowledge, educate, and support others entering the space, in ways that had never happened before in Australia.

In 2010, MAPS founder Rick Doblin was invited to speak at that year’s EGA Symposium. A workshop held after the event led to the formation of Psychedelic Research in Science & Medicine (PRISM), which is now Australia’s leading psychedelic research charity. The EGA conferences are now recognized as one of the longest-running psychedelic conferences.

Honoring the History of the Australian Psychedelic Underground

The option to use psychedelics within a therapeutic context in Australia is promising, though many professionals entering this space may be unaware of the importance of the underground work, which laid the foundation to understanding effects, how to use psychedelics safely, the problems around consent, and also how to integrate the psychedelic experience.

As the space around psychedelics change, there is a need for reflection on how far our understanding of these substances have come by virtue of underground researchers. While building on the work of traditional practices, and prior research, there is, perhaps, also a need to consider a contemporary approach, reflecting on underground practices in an attempt to create a modern approach to psychedelics without appropriating traditional practices.

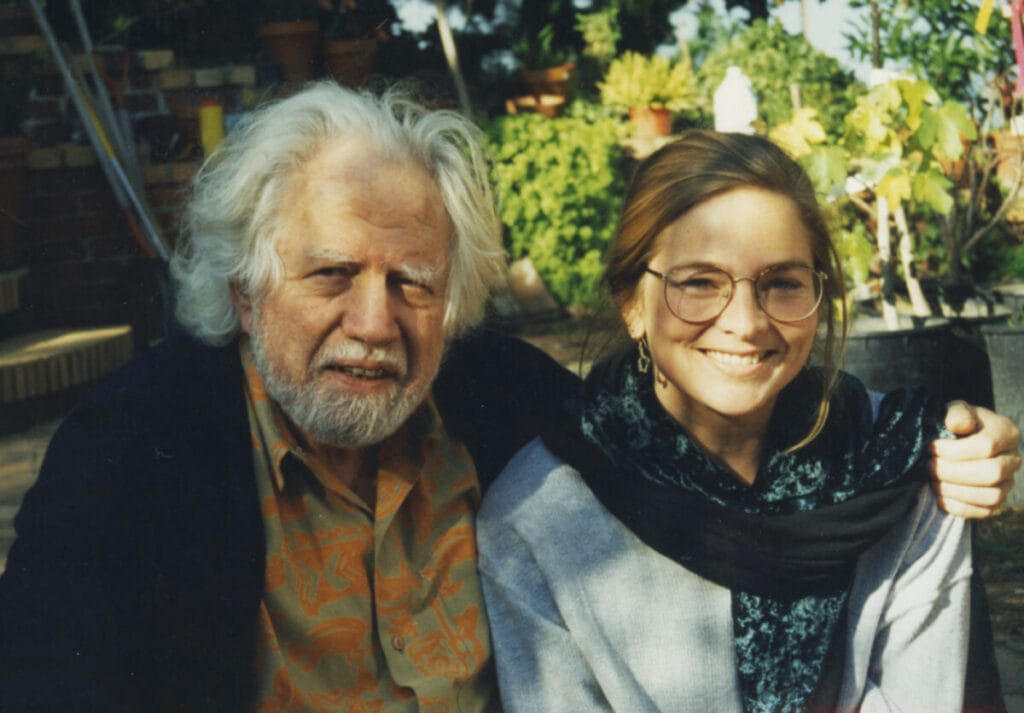

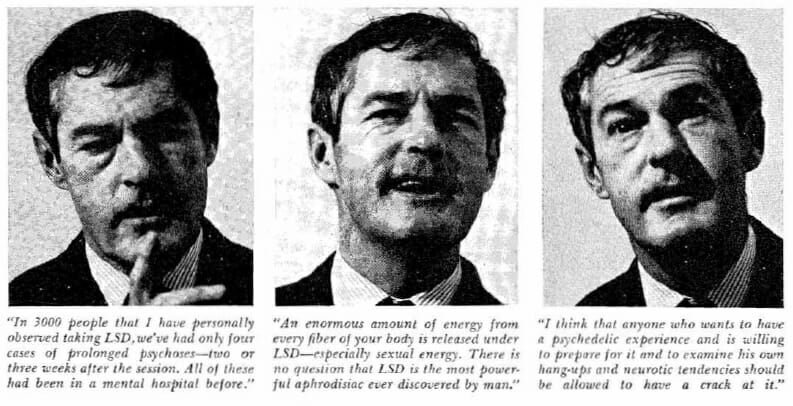

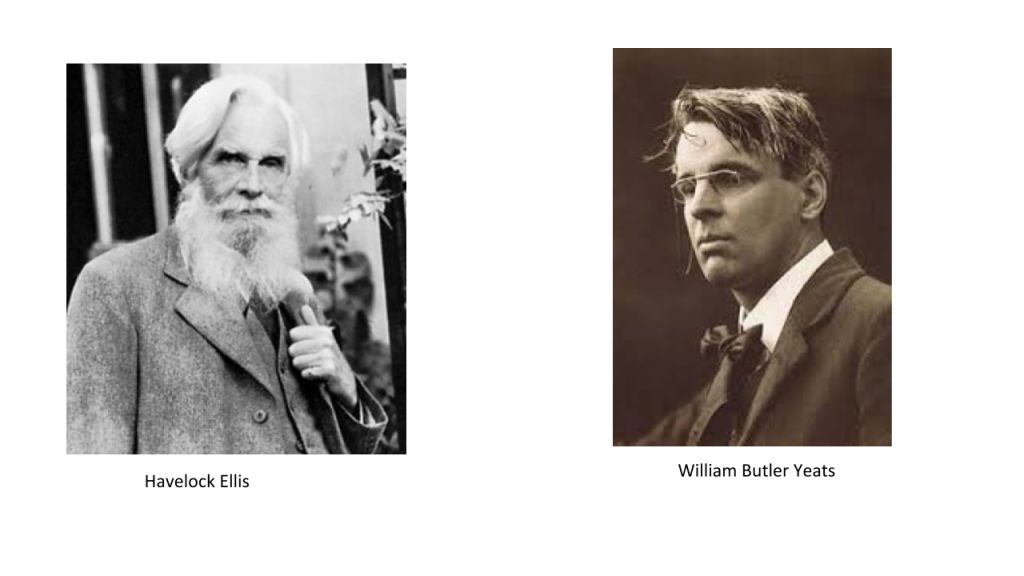

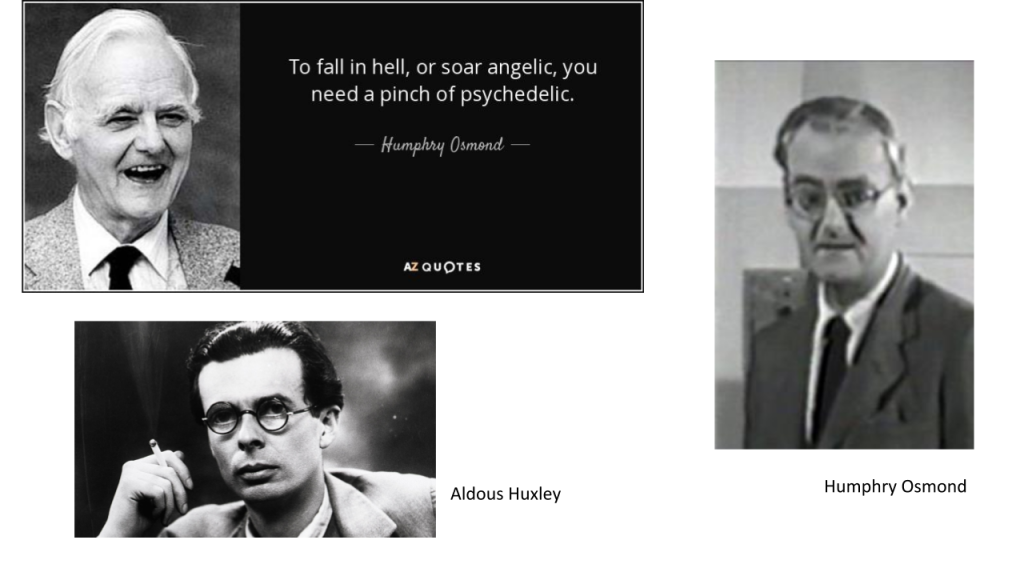

Humphry Osmond worked a little mental hospital up in Saskatchewan and began experimenting with LSD [and mescaline]. Aldous Huxley somehow learned of this work and said, “If you’re in LA, come by and see me.” Osmond didn’t think it would ever happen, but in fact, there was a bureaucratic problem at the hospital. They needed to reorganize and move Osmond up and get rid of the guy that was above him, and so while they were doing that, they sent Osmond off to an APA convention in LA – where he got in touch with Huxley. They went to a few sessions of the APA convention and were bored to tears. So they adjourned back to Huxley’s place and Osmond turned him on. It took about 90 minutes before it really hit him and then it blew his mind. Huxley was the author of Brave New World and Ape and Essence. Huxley was one of the major intellectuals in the 20th century and an enormously successful author, half blind, but intensely intellectual. He was part of a circle of people that stretches back really to Havelock Ellis and Hermann Hesse [Who wrote Siddhartha and

Humphry Osmond worked a little mental hospital up in Saskatchewan and began experimenting with LSD [and mescaline]. Aldous Huxley somehow learned of this work and said, “If you’re in LA, come by and see me.” Osmond didn’t think it would ever happen, but in fact, there was a bureaucratic problem at the hospital. They needed to reorganize and move Osmond up and get rid of the guy that was above him, and so while they were doing that, they sent Osmond off to an APA convention in LA – where he got in touch with Huxley. They went to a few sessions of the APA convention and were bored to tears. So they adjourned back to Huxley’s place and Osmond turned him on. It took about 90 minutes before it really hit him and then it blew his mind. Huxley was the author of Brave New World and Ape and Essence. Huxley was one of the major intellectuals in the 20th century and an enormously successful author, half blind, but intensely intellectual. He was part of a circle of people that stretches back really to Havelock Ellis and Hermann Hesse [Who wrote Siddhartha and

supportive ways, working collectively toward shared goals while enhancing the personal journey of each individual. Cosmic Sister promotes love, higher consciousness, abundance and creativity, and members pledge to hold each other’s best interests at heart as allies and affiliates. We want to see women shine.

supportive ways, working collectively toward shared goals while enhancing the personal journey of each individual. Cosmic Sister promotes love, higher consciousness, abundance and creativity, and members pledge to hold each other’s best interests at heart as allies and affiliates. We want to see women shine.