When you realize that you’re not who you thought you were, the spiritual leader Ram Dass used to say, the path to enlightenment begins. This is also the beginning of the journey for LGBTQIA+ people.

In either case, self-realization can be prompted by psychedelics. But that transition is a scary one: whether it’s your ego or the gender and sexual orientation you were assigned at birth, it requires the death of the person you’ve known. Ultimately, you break through into a place of beauty, truth, and love. But there’s usually a period of kicking and screaming first, trying to hold on as the known slips through your fingers.

For queer and gender-diverse people, it often isn’t safe to express or connect with who we are, so we learn to suppress this knowledge even from ourselves. Denying one’s authenticity causes trauma that can manifest as depression, anxiety, and PTSD. But LGBTQIA+ researchers, therapists, users, and underground practitioners are finding that psychedelic therapy has immense potential to help their communities heal from internalized queer- and transphobia.

Lxo, a London-based artist and research curator experimented with various medicines in art school when their queer, trans*, and non-binary identities began to surface, deposited by a repressive, religious upbringing and persisting through more than five years of talk therapy.

“Then I did one [dose] of s-ketamine, and something burst forward from the past, like a memory bubble” they say. “I was able to forgive and heal… the version of me that was really crying out for help.”

There Is No “Post-Trauma”

For queer and gender-diverse people, there is no “post-trauma,” says Dr. Jae Sevelius, a clinical psychologist and Professor of Medical Psychology in the Department of Psychiatry at Columbia University Medical Center. Rather, it’s ongoing, and “It’s not just about experiencing violence, it’s about experiencing violence because of who you are.”

This has manifested in anti-trans legislation across the U.S., Colorado’s Club Q shooting, and Uganda’s horrific bill making homosexuality punishable by death; woven into the fabric of society in the form of hetero-, cis-, and mononormativity. In most places, even meeting the primal need of relieving yourself involves an act of self-denial.

Discovering who you really are should be a joyful revelation, but is still often met with violent opposition. Most suicide attempts occur within the first five years of realizing one’s sexual identity, irrespective of age; for many, this is during youth. More than half of U.S. trans and non-binary people age 13 – 24 considered killing themselves in 2020, while queer teens attempt suicide at a rate more than twice that of their straight peers.

Most mainstream therapies, however, treat trauma as an isolated incident. “[In the West,] we don’t have great approaches to offer people,” Sevelius says. “We have medicines that can treat the symptoms… but talk therapies for trauma… can be really challenging, [with] very high dropout and [low] success rates.”

What’s more, these frameworks aren’t built to support the queer experience. On the contrary, they’re often the very sources of the trauma they aim to treat. Homosexuality was still classified as a mental illness in the American Psychiatric Association’s (APA) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) until 1973; being transgender, until 2012. These links persist today, with gender-diverse people being required to undergo psychiatric evaluation before receiving supportive healthcare—assuming this is even an option.

I’ve experienced this firsthand: celebrating diagnoses that pathologize your identity because it means you can actually get the care you need, reinforcing cognitive dissonance and negative self-beliefs. It breeds mistrust among queer and especially gender-diverse people, especially those with intersecting underrepresented identities, such as BIPOC and sex workers, who face additional systemic barriers and are most impacted by the drug war.

Patients often have to educate their therapists and doctors in culturally relevant care, emotional labor that can be life-threatening. Even worse, queer and gender-diverse communities have been subjected to so-called conversion therapy, inhumane “treatments” that try to turn people cisgendered and straight, still legal in many places. Methods of administration have included electroconvulsive therapy — and psychedelics.

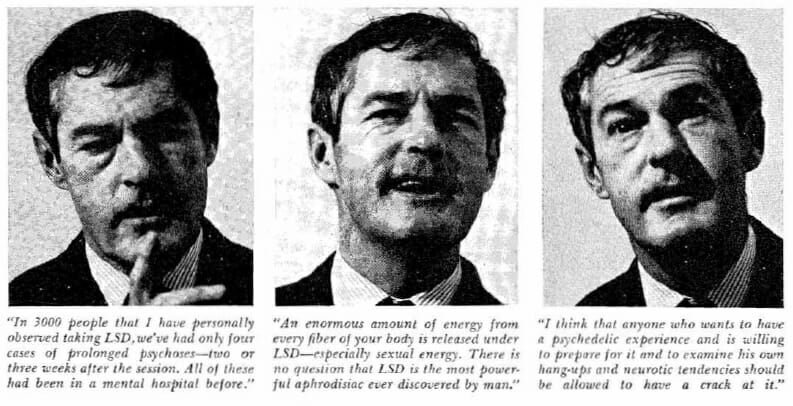

In 1950s and ’60s France, gay teens who had been institutionalized for the double “offense” of being gay and out were forced to take megadoses of LSD — up to 1200MG, three times the recommended maximum — then left alone in a room to be observed. Even Ram Dass — before his awakening, when he was still called Richard Alpert, a clinical psychologist, professor, and founding member of the Harvard Psilocybin Project — joined the likes of Timothy Leary and Stanislav Grof in similar experiments.

In 1968, a Playboy interviewer questioned Leary about reports of LSD bringing forth “latent homosexual impulses,” to which Leary called the drug a “cure” for such “sexual perversions.” This approach scared some people into living straight lives, but most reported “relapse.” Ram Dass himself came out in the 1990s, but rarely spoke publicly about this fundamental aspect of self, struggling his whole life with internalized shame.

Rethinking Clinical Frameworks

The fact that substances known as truth agents could be used as tools of oppression speaks to the influence of set and setting – and, perhaps even more, of institutions like medicine, psychotherapy, and the university system, where outcomes must align with conclusions that satisfy funding sources.

Today, the barriers to both gender-affirming treatment and psychedelic healing remain immense. Part of the problem is that LGBTQIA+ people are underrepresented on both sides of psychedelic therapy and research, as well as the sciences more broadly, and largely feel unwelcome in all these arenas.

“We need to recognize that there are specific needs between different people within the community, and those needs arise from systemic failures,” says Alfredo Carpineti, a queer astrophysicist and founder of UK charity Pride in STEM.

Research both reflects and creates the world, as psychologist and Yale researcher Terence Ching and others have observed. Psychedelic clinical trials and research studies don’t even gather data on sexual orientation and gender identity, so there is no way to know how psychedelic therapy impacts LGBTQIA+ communities, yet the message this sends to them is clear.

Existing studies and trials are not designed to capture or accommodate queer experiences, typically using cis-het, male-female therapist dyads that are meant to mimic hetero-normative parenting frameworks. Additionally, therapists are not trained to handle complex gender and sexuality issues that may come up during sessions.

Misgendering or failing to affirm someone’s identity can be particularly wounding, Sevelius warns. Those designing studies need to ask who is training and recruiting the therapists, and where they’re recruiting participants. A study on MDMA therapy for gender-diverse populations that they contributed to found current protocols lacking, calling for explicitly gender-affirming treatment and safer, more inclusive settings.

“I get requests all the time from trans and gender-diverse people asking me how they can be included in clinical trials. And I have to say, I don’t feel comfortable referring people,” Sevelius says. “Psychedelics create a very vulnerable psychological state. When you don’t know whether the therapists are really competent to be working with our communities, it’s very likely someone will get re-traumatized.”

Psychedelic research also needs to more rigorously capture demographic data about sexual and gender identity, but most organizations don’t have the resources, Ching says. Still, it’s crucial to recruit and train more LGBTQIA+ researchers and therapists to support straight ones in building queer-inclusive clinical spaces.

“There are many ways to improve access,” Ching says. “Rethink your eligibility criteria [and] do more than put up fliers. Go to queer organizations, talk to people, … do a town hall. Tell them what PTSD is and actually get savvy with the fact that sexism, racism, homophobia, and transphobia can lead to it.”

You’re Not Who You Thought You Were

Saoirse* spent five years in the military police, presenting masculine as a means of survival. Struggling with “decades of suppression and depression as well as PTSD from growing up in cis-het society and from the military,” she had already done a decade’s worth of talk therapy through the VA, cognitive processing therapy (CPT; a cognitive behavioral therapy for PTSD), and couples counseling. Then she participated in an ayahuasca ceremony.

“Having a safe space to explore my beingness… within a [sacred container and] Peruvian Amazonian lineage… was the key for me in discovering my true essence,” she says. “The masculine persona… dropped away. The other women gathered around me in a group hug, and I felt my true self seen, held, and celebrated for the first time.”

Talk-based approaches like cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) are standard treatment for afflictions like addiction and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), but these focus on managing present symptoms rather than targeting the trauma at its roots.

During his own MDMA therapy session, Ching was visited by otherworldly animal entities that helped him reconcile his queer and Asian-American identities, which he describes as “a profound experience of unshackling myself from the confines of internalized homophobia.”

Dee Adams, a research program manager at Johns Hopkins University who studies the impact of psychedelic therapy on gender-diverse people, says, “Psychedelics unlock[ed] those pieces of me that I… didn’t have the courage in mundane reality to approach or be aware of. I don’t know of any [other] medicines that can… be directly attributed to that initial ‘aha’ moment.”

Psilocybin and LSD have huge potential in triggering these insights, Sevelius says, as they’re known to break stuck patterns. MDMA is effective for identity-based trauma because it increases self-compassion and empathy, they add, and can improve gender resiliency when combined with affirming care. Along with a New York-based clinical partner, they’re also developing the first ketamine-assisted group therapy study created by and for trans and gender-diverse people.

Yet the relief goes beyond clinical symptoms. In her ayahuasca journeys, Saoirse connected with not only her own femininity but the feminine archetype, transmitted through the spirit of her mother, who was dying of a brain tumor.

“Spirit gifted me with an experience of the female pain body… and all the feminine has held for the masculine throughout the ages,” she says, including “the damage the masculine has done to itself… in committing violence. I was shown the breadth of our journey as souls through lifetimes and the beautiful and terrible dance of the human story.”

She also experienced reconciling with her mother’s spirit from her painful first coming-out, something antidepressants and talk therapy could never provide. “Healing does not occur in the mind,” Saoirse says. “Especially [when] healing core wounds with identity and gender identity, [it] takes place in the heart, … in belonging, and sacred witnessing of our stories, held in the eyes of love.”

Three Key Words: I See You

We all need to be seen and loved exactly as we are; it’s a fundamental human need, second only to physical survival and safety. Constantly being disaffirmed by others can cause what Sevelius terms “identity threat,” manifesting in mental health issues, isolation, and substance overuse.

The cure is increasing affirmation while reducing reliance on external validation; psychedelic therapy, they explain, can do both. Affirmation comes from therapists and the sense of connection to larger, mystical forces; the medicines help people validate their own being.

But deconstructing and reconstructing your self-concept is a monumental task; often an entire life’s work. With any psychedelic journey, but especially for LGBTQIA+ users, support before, during, and after the session is essential. Shortcomings of the current clinical framework — not to mention the dubious legal status of most medicines — means many may be better-served by shamanic, Indigenous, and underground providers, something queer researchers confirm.

“Even as a scientist, I don’t necessarily always advocate that the clinical trial is better,” Ching says. “There are some ways of knowing, like gray literature [research published outside formal academic channels] or having your own personal experience, that might be more beneficial than reading it in a scientific journal.”

For Adams, the approaches go hand in hand. Psychotherapy and prescription medication might be additional tools people use for ongoing support after psychedelics bring them the initial realization.

Peer-support networks can be incredibly helpful, providing that essential component for healing: affirmation. Groups such as the Queer Psychedelic Society and Transadelic connect LGBTQIA+ people who use psychedelics through messaging platforms and integration circles. Many trans and gender-diverse people, in particular, find connecting with like-minded others crucial.

“There was a time when our culture was celebrating queerness, but [you had to be] a specific type of queer. I think people are still having and perpetuating that trauma,” says Transadelic member Casey*. “I don’t seek out queer spaces. But I’m really grateful for this one.”

For Saoirse, “hav[ing] my transition journey of self-discovery held… within a conscious spiritual community… has made all the difference for my self-acceptance, self-love, self-confidence, and my quality of life.”

A Queer Medicine

The links between psychedelics, queer culture, and esotericism trace back to spiritual traditions and early LGBTQIA+ rights movements. In the 1960s and ’70s, groups such as the Cockettes and Radical Faeries challenged social norms and blurred counter-cultural boundaries, sprinkled with consciousness-expanding practices.

In fact, the Pride flag was conceived of during an acid trip in the era when the 60’s hippie culture began yielding to ’70s club culture, and queer people found community and catharsis on the dance floor using MDMA and LSD. The myriad colors reflecting off the mirrored disco ball inspired the flag’s late creator, Gilbert Baker, as a symbol that could replace the former logo, the upside-down pink triangle reclaimed from the Nazis.

Psychedelics have inherent queerness: interwoven into Indigenous societies with fluid conceptions of gender and sexuality; inverting expectations and challenging norms; releasing rigid patterns and making new connections, from found family to community care and long-neglected parts of yourself. One species of fungi has more than 23,000 distinct sexual identities; as mycologist Merlin Sheldrake observes, it helps scientists think beyond the binary, mirroring queer theory and reflecting the world in its crystalline multiplicity.

In the psychedelic state, “the dissolution of ego boundaries becomes the dissolution of binary categories,” Lxo observes, and integration “begins to connect and unify them, bringing all the various different energies, even seemingly binary ones like masculine and feminine, into a kind of relation.”

It’s crucial for the clinical establishment to understand that queer and transness isn’t something that needs to be cured — and tying treatment to disorders and diagnoses echoes of the pathologized past. Sevelius says the focus should be healing past wounds while building coping strategies for facing continual trauma. Meanwhile, Ching wants to see psychedelic therapy “targeted to identity-affirmation processes… fostering the wellbeing and actualization of queer folks.

“Psychedelics have the power to shift the way we see and experience the world, including ourselves, remembering who we were before a traumatized culture had its way with us. As Ching says, “I know I was born this way, but it took MDMA to show it to me, to accept the emotional truth, … and live my life according[ly].”

Editor’s note: Some names have been changed to protect the identity of the source.*