An NYU psilocybin depression study participant discovers an unforeseen application for psychedelics: the treatment of chronic pain. Part 1 of the series: Psychedelics and Chronic Pain.

Everything Worked, but Nothing Lasted

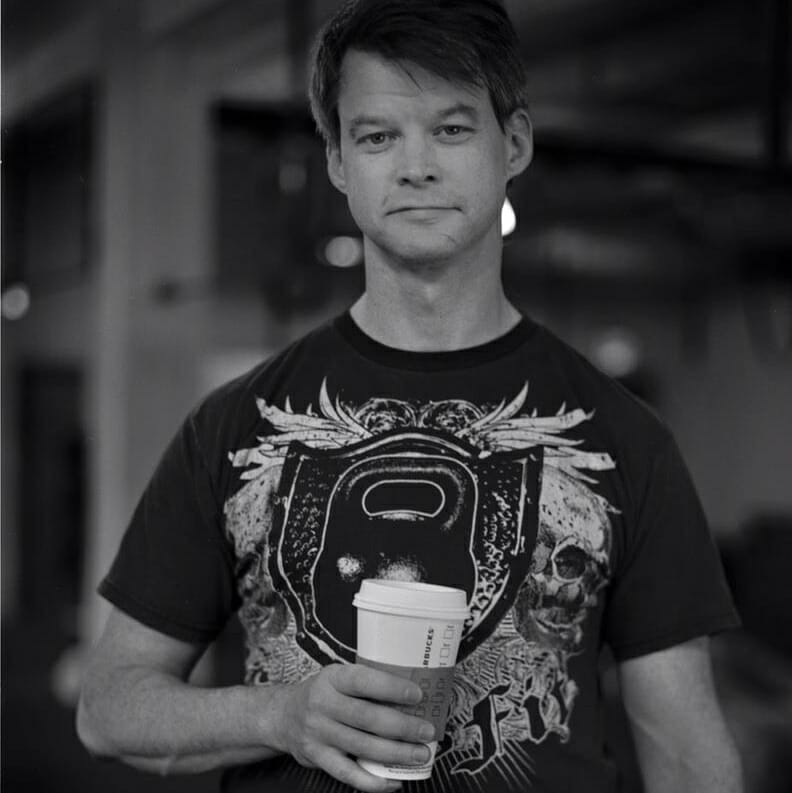

In the fall of 2020, I was living a pretty successful and happy life – on paper. I had co-founded a very popular, leading-edge CrossFit gym in NYC; one of the first in the world. I held multiple advanced certifications in applied neurophysiology through Z-Health, helping clients with challenging pain and performance issues. As an early adopter of kettlebell training, I became a nationally top-reviewed instructor and trained Team 6 Navy SEALs, astronauts, pro athletes, wounded veterans, and members of the FBI, NYPD, NYFD, and ROTC. I was featured in Men’s Fitness, the NY Times Sunday Routine, and USA Today. I had 30 years in the pain & performance field, training and teaching at a high level, and was becoming widely known for helping people with difficult mobility problems or chronic pain, using unique methods from the leading edge of neurological rehabilitation. On top of all of that, I was 17 years sober.

However, not all that glitters is gold. A now ex-business partner was committing a Ponzi scheme to the tune of millions, and his case followed him like a shadow, turning my life’s passion into an emotionally and financially toxic nightmare that economically devastated my family. My best friend, Kirk MacLeod, who I had completely rehabbed from chemo & cancer surgery, died six months after being declared in remission. My first son had developed undiagnosed GERD and couldn’t sleep more than an hour and half at a time, which meant my wife and I slept even less.

Unsurprisingly, my episodic depression returned after more than a decade and a half, and I was now increasingly treatment-resistant; unresponsive to psychiatric drugs that had previously worked. All my pain neuromodulation interventions that worked on my clients no longer worked for me, and I had developed chronic pain myself.

I share all my background here to demonstrate that I was not under-resourced in either knowledge, networks, or diversity of approaches, practice, or experiences. I poured over all my certification materials looking for anything I had missed, but had fallen into an increasingly deeper recovery hole; everything worked, but nothing lasted. I was hitting a new bottom in my life, deeply sinking into the midst of an increasingly treatment-resistant depression episode that had likely been ongoing for five years.

But then I became aware of ongoing studies on psilocybin for depression happening locally in NYC. I had experienced a few high-dose psychedelic sessions nearly a quarter century ago and had been an avid Terence McKenna fan (even speaking with him directly after a lecture in Seattle), but I had never taken psychedelics therapeutically, and my recreational interest had effectively vanished once I became sober from alcohol. Intrigued, I connected with the local clinical research coordinator, Leila Ghazhal, at the NYU for the clinical trial of Psilocybin for Major Depressive Disorder study (sponsored by the Usona Institute), and took all the online and over-the-phone assessments, passing them easily. The primary investigator (PI) on my study was Dr. Stephen Ross, who had been leading psychedelic research at NYU for more than a decade. Amazingly, I made it into the trial within a month and a half, learning that I’d actually beat out 8500 other applicants for just 100 spots nationwide.

Trying Not to Hope

When I first entered the trial, I was in a state of denial about how severe my depression was, but once I took the MADRS assessment, there was no avoiding that I had moderate to severe depression with suicidal ideation.

I remember a specific moment very well during this process, when I was finally cleared to enter the study and the study coordinator was speaking with me about the results of my assessment and my upcoming participation. I asked what would happen if I didn’t receive psilocybin during my session, and he reassured me that they would not just drop me off in the middle of the ocean to dog paddle – that there were other interventions and studies available and they would be sure to find me something, but there was a good chance I would receive psilocybin and hopefully get some good results. At this point, my mask cracked a little bit and some protective cynicism came out, and I quipped with a bit of a shrug: “Well, we’ll see.” I hadn’t meant it to be dismissive or sarcastic but it came out that way, and the conversational atmosphere rapidly shifted. He looked right at me and suddenly he wasn’t the primary investigator anymore, lost in the myriad details and logistics of a very involved study. Now he was the deeply experienced clinician and therapist, and, having heard something within the tone of my voice, dropped all the way in and asked softly: “What’s going on behind that, Court?” Suddenly, all the masking dropped and there was no more place to hide because I was so, so tired at this point, and had been waiting for this moment. In and out of therapy for years, dozens if not 100 self-help books, so many modalities, so many somatic systems, and here I was with a chance for something new to help me. When I realized why there was cynicism behind my statement, my voice cracked, I started crying, and I answered him: “Trying not to hope.”

The one glimmer of hope I did have was reading a 2018 paper by lead author Calvin Ly describing psychedelics’ neuroplastic activity in the prefrontal cortex. As someone who had studied the neurology of pain for years, this was revelatory. Many pain conditions are, in fact, nociplastic or noxious conditions arising out of the central nervous system (CNS); there’s no more injury or damage if there ever was, but your CNS is still continuing to put out a maladaptive alarm signal that is perceived as pain. So learning that psilocybin was creating actual structural change within my cortex – not “just” psychological change – was completely astonishing.

My dosing date was on March 5, 2020, and I remember looking down at the capsule sitting in the cup, saying to it: “I really hope that’s you.” I was terrified inwardly that I would receive the placebo, that I wouldn’t respond to the psilocybin, or that it would only work just a little bit, only for its effects to slowly fade. But within half an hour, there was no denying that I had received psilocybin, and I earnestly pursued all the procedures everyone on my care team at NYU had worked with me on for weeks in preparation for this day.

I was genuinely shocked at the sheer volume of psychological material from my childhood and early adulthood that came up. I had profound transpersonal experiences and healing, revisiting instances that were pivotal in my childhood. I had an encounter with the first woman I had ever loved, who had committed suicide three years after we had broken up. Her death had caused a profound grief in me that drove my drinking for a decade after. I thought I had released the majority of my grief around her once I got sober, but clearly, there was so much more to heal that had been deeply suppressed as I tried to move forward with my life.

Reset, Renewed, and Reborn

The biggest shock of all, though, was waiting for me at the end of the day when one of my facilitators casually pitched a seemingly routine question while closely watching me out of the corner of his eye: “So, how do you feel?” Without thinking, I reflexively replied, “Good,” but then, just as reflexively, scanned more deeply inward, and in a sudden rush, realized my depression was completely gone – not just better, but vanquished, exclaiming: “Good! That fast? Are you fucking kidding me, that fast? Is it gone already?”

It felt as if a huge mass had been surgically removed from me or as if an entire continent within my interior was now suddenly revealed. No matter how many times you read the word “remission” and the percentages behind it in scientific studies, very little will prepare you for the shocking reality of it. The contrast between before and after was profound. All of the iterative rumination was gone, and it took no effort for that to happen. And it only seemed to strengthen as the days passed. Miraculously, all suicidal thoughts ceased on that day and never returned.

Shockingly, only ten days after my dosing session, NYC went into a complete pandemic lockdown, my entire industry closed, and my two young boys were now at home with me 24/7, tele-learning. I cannot imagine what 2020 would have been like for me if I had received the placebo. It’s almost unimaginable.

But here is where the story takes an even more profound and impactful turn. During the session, my leg started intensely tremoring/spasming. I had been evaluated for musculoskeletal pain and dysfunction that I had acquired through a host of injuries over the years of my performance career, and in fact, had just been in the doctor’s office a few months earlier trying to determine if I had arthritis or something worse. But right there in the session room, I started having a neurological revision, with my muscles and nerves in my right inner thigh firing in an effort to recalibrate the sensory and motor inputs and outputs in that part of my kinetic chain. It was almost like a self-generated TENS unit (Transdermal Electromagnetic Nerve Stimulation, used to generate muscle contractions and neuromodulate pain signals with micro-electric pulses) getting my leg back online by creating intense motor activity in the muscles of my thigh.

I’ve since spoken with spinal injury survivor Jim Harris and read a case series from UC San Diego’s Psychedelics and Health Research Initiative (PHRI) published in PAIN Journal where the exact same thing occurred to them under the effect of psilocybin with the same positive results, but at the time, the facilitators were concerned enough to ask the primary investigator to come and evaluate me during the session. I had to explain to him, somewhat hilariously as I was going into my peak, that, in fact, the tremors felt intensely good. I’m grateful that he let them continue because it has made all the difference.

While I partially understood what had happened, I was understandably beyond eager to learn more, and to see where else this realization could take me: Why did this work so well? Has our understanding of chronic pain been wrong? And if psychedelics are the answer, what does treating chronic pain with psychedelics actually look like?

This is part 1 of a 2-part piece and part of a larger series on chronic pain and psychedelics. In part 2, I will dive into the research around remapping and mirror box therapy, and why my psychedelic experience seemed to be so effective.

Future articles will focus on: What is pain and what causes chronic pain, old assumptions vs. new science, the suspected mechanisms of action behind the interaction between psychedelics and pain, and best practices and safety concerns for working with psychedelics to alleviate chronic pain.