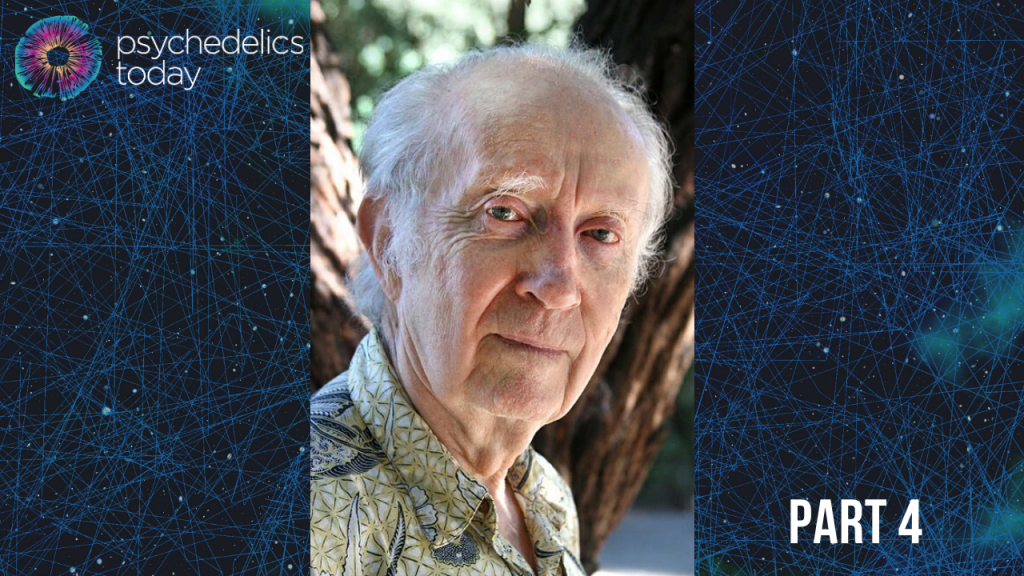

This is the fourth and final blog of a podcast recorded in John Cobb’s apartment in Claremont, California. This was recorded during a small weekend conference on psychedelics titled “Exceptional Experience Conference.” You can listen to the full talk in this episode of Psychedelics Today.

John Boswell Cobb Jr. is an American theologian, philosopher, and environmentalist. Cobb is often regarded as the preeminent scholar in the field of process philosophy and process theology, the school of thought associated with the philosophy of Alfred North Whitehead.

John Cobb: Obviously, I’m not going to put this forward as a great psychedelic experience, it still doesn’t feel like it’s just simply my talking to myself. It feels like I didn’t know what to do. I hadn’t thought about this before. Suddenly, yes, of course, that’s what I need to do.

Kyle: It feels like it comes from somewhere else, but it is inside.

John Cobb: But of course somewhere else is not as special somewhere else.

Kyle: Right.

John Cobb: It doesn’t come out of my normal ego consciousness. It feels like that there’s a wisdom in it that was not my wisdom. There’s an otherness about it.

Kyle: Right. And that it’s coming from somewhere.

John Cobb: I know. They’re coming from somewhere, it is immediately… Vision is so spatially oriented that if we talked in a visual language somewhere else is going to be very prominent. With just hearing music, the location of the music isn’t that important, is it? It’s the music in your ear or is it inside your body? Is it in the airwaves around you? Is it where the orchestra is? Well, yeah, any and all of the above. But you see a book, all right, that book is on top of that book. It’s so very clearly located and each object that you see has boundaries. And so that just creates a language and a culture.

The difference between Gautama and the other great Indian thinkers, for Gautama when you seek the self, there is nothing. But the others there is Atman, and Atman is the same as Brahman. The ultimate substance. And Gautama and many of the Buddhists assume that if you conceptualize at all, you will be misled. That just shows how powerful concept and visualizing is such a scene too. Whereas I belong to the view that it should be possible to have… like Bohm was saying, “Okay, let’s just use gerunds.” I don’t think it’s impossible to conceive process. That’s the part, I hope you understand, this is not me anti-Buddhist. I think it’s amazing that 2,500 years ago somebody was able to think so deeply. I regret that the tendency even today is to become anti-concept, when what we need are better concepts.

Joe: Yeah. I’m feeling like you say you can’t skillfully conceptualize process, but perhaps it’s more about feeling like

John Cobb: You can conceptualize feelings.

Kyle: Right. True.

John Cobb: It’s just that our Indo-European languages haven’t, so you can’t quickly think of examples.

Joe: That’s interesting.

John Cobb: And conceptualize maybe the wrong term. But I don’t like a kind of retreat into mysticism. If you say it’s mystical, then you say you can’t think about it anymore. I think we can think about it, and if you don’t want to call it concepts, call it whatever you want. But we can think about processes. And science needs to think about them. And thinking about them doesn’t necessary… I mean, what it has so often meant is locate it in a sight oriented world or substance oriented world, then you’ll see then you’re not really thinking about them anymore. Anyway, that’s why David, I think, has done a remarkable job of thinking about process. And has given us a language that can help us do it. And I think that’s very useful.

Joe: Yeah, I think it’s really helped me quite a bit with perhaps handling psychedelic experiences with a little more grace because it’s not so… Just Lenny has put a lot of this knowledge on us and it seems like it’s really helpful. And it’s hard to put, for me, at this point, to really phrase that well. But it’s certainly been a Boon.

Johanna: What was the one thing that was helpful for you? I’m sure there’s lots of things.

Joe: Lenny’s complicated. And as a result that…. probably more of a gerund type attitude towards the thing as opposed to this is this, this is an Apple. It’s more like, wow, this is just a dynamic flow of things through this very complicated system.

John Cobb: I see. I don’t know Chinese, so my statement that it is not so substance oriented. But when I’ve tried to talk about this with Shahar he points out that the same character can function as either.

Joe: Oh, wow.

John Cobb: An example of a word that this has happened to in English is the word pastor. It was a noun for a long time. You were a pastor. But now people talk about, “I’m going to pastor such and such a church.” No, I think that that gets closer to reality to say a person is a pastor, what does it mean? It means that he pastors. But when you locate it as a pastor, it’s just sort of strengthens this individualistic thinking rather than a focus on the activity.

Kyle: It is versus it’s doing or it’s happening.

John Cobb: Yeah. Well to pastor people means you listen to them when they have something to say and you hear them without judgment. I could go on and on. But that’s what a pastor does. And to call a pastor is really to be pointing into that dimension of activity. The same person who is a pastor is also a preacher, but unfortunately we have a verb to preach so we don’t say to preacher. I just wish there were more cases where I could point to how a noun has just come to be used as a verb. And there are others, but at the moment I’m not thinking of them.

Joe: Do you recall the first time you heard something that made you interested in the positive impact of psychedelics or anything around the beginning?

John Cobb: Lenny was certainly one of the early ones. But I don’t want to say his first because I just don’t know.

Johanna: Right. It was southern California in that period of time when it was probably pretty intense.

John Cobb: But obviously having him, he was really trying to convert me. I appreciated it. This is not a criticism. Anytime one discovers something that’s very helpful, one wants other people to benefit from it. So my relation to him was the first time this had become something that I really had to deal with. But that doesn’t mean I hadn’t heard of it before. Probably I had heard of it more negatively than positively. Because of course the hippie culture included some negatives. I grew up in a context where drinking was already a bad thing to do. And the tendency in circles I moved in, which by that time has ceased to be particularly strongly against drinking, was to associate alcohol and psychedelics.

I was quite sure alcohol did a lot of harm as well as working well for conviviality… You know what I mean. Of a mixture. So I thought psychedelics, and I had no doubt that some people had great experiences and other people that may found them very attractive, but it… Generally, I suspected that society was better off not to have it. So Lenny was probably the first person who really opened my eyes to the potential of very positive use.

I had another experience not too long after I came to Claremont. I had always assumed that civilization was a good thing. There was a professor at Pitzer College, who I worked with quite closely. We co-taught courses. He was very convinced that civilization was the basic evil. I’m not convinced. I mean I think every civilization we’ve had has been pretty horrible. I wouldn’t have said that if I hadn’t had to interact with him about that. But I think if there are people today of course, who just think we need to get rid of civilizations and then we’ll be all right. My impression is today it would be very remarkable if 10% of the world’s population survive without civilization.

Even though I appreciated his opening my eyes, I didn’t walk through that door. And the same thing was true with Lenny, I really appreciated his opening my eyes, but I didn’t walk through that door.

Kyle: I appreciate your openness and curiosity of the subject. For somebody that didn’t walk through the door, you seem to very curious about it.

John Cobb: I’m confident there’s much good that could come from it. And so when there are people who are using it for good, I want to be as supportive as I possibly can. A lot of people today will say, “Yes, we really need basic changes.” But you know what it means to make basic changes in worldview, and most of them don’t. So it’s very comfortable to be in a group of people who when they talk about changes, they know what the-

Joe: Extraordinary change.

John Cobb: Yes.

Joe: Yeah.

John Cobb: Whitehead has made me understand what I think would be the changes that might make us behave in responsible ways. So I don’t feel the necessity of having unusual experiences.

Johanna: And what would be some of those changes?

John Cobb: Have to change from our substance thinking to our process thinking. This would be a change from our thinking of every individual as self-contained, to understanding that we are all our products of our relationships with each other, and that the human individual is… Well, for one thing, I mean from Whiteheadian viewpoint, any individual is the many becoming one. That’s what it is to be an individual. So to be an individual is to be part of everything, is to have everything being part of us.

Economics, as an example, I think economics is the worst, because it is the most powerful shaper of the world and is the worst expression of the university. It assumes radically individual and really the only relationships that count are economic relationships. I think those are just two absolutely erroneous views. If they are not changed, then they have to be changed existentially, not just, oh, that philosophy might work better or something. And it’s because what you do helps to make the existential change that I in no way want to say, “Oh, all we have to do is to do philosophy.” No, no. I think the change has to go way beyond that.

I had one experience out there, which made me very high. So in that sense, but it had nothing, it wasn’t a matter of breathing exercises. It was being in a group where I just felt completely accepted, completely loved. I think that can happen just by the way a group of human beings relate to one another. I was still feeling that deep comfort when I came home. It took my wife a little while to puncture the balloon. So I’m not suggesting that everybody should always be in that state, but nevertheless that’s a feeling of being one with that group of people that people need. The church should be doing this. I’m not trying to push me into the church, you should understand that’s important for me in my understanding.

When I was in the army, one night I said, “Kneel beside my bed.” And the whole room just simply itself felt like it was filled with love and acceptance. You’re not just an individual when that kind of thing happens. You are part of something else. So I’m just saying you could call them psychedelic experiences, if you want, they don’t have many of the characteristics that people describe as psychedelic, but they are experiences of a different possibility that is still a perfectly human possibility.

There is a woman by the name of [unclear Thandeka 01:13:05]. She’s Afro-American and Bishop Tutu. He gave her the name. And she’s spent a lot of times studying neuroscience and gotten getting acquainted with key people in the field. And she’s created an organization called Love Beyond Belief. She seems to be able to help. She’s Unitarian, and she has worked with Unitarian churches, which are not the places that I would have thought, which I say most readily, but sometimes it turns out that people who have been putting all their emphasis upon reason and rationality and so forth, other ones who are really ready for something else. She thinks it’s possible to organize a service of worship in such a way that people will really existentially feel loved. And to whatever extent she can do that, I think that will accomplish much of what I’m interested in. But obviously a number of people in this group, and in almost any group I’m at, have had a completely different experience of a church. That church is a place of judgment and condemnation and guilt and all of that. And that is of course the absolutely opposite of what is needed.

I think the church has great potential for good. It has great potential for evil. It’s like almost everything else. Education has great potentials for good, great potentials for evil. And I think the modern world has tended to bring out the potential for evil in both. But that doesn’t mean, I think, in the middle ages everything was wonderful. I really think Europe was better off in the middle ages than it has been in modernity. But I’m not interested in going back.

Links

Website

Process Theology: An Introductory Exposition

Other books by John Cobb Jr.

A Christian Natural Theology, Second Edition: Based on the Thought of Alfred North Whitehead

Jesus’ Abba: The God Who Has Not Failed

Grace & Responsibility: A Wesleyan Theology for Today

For Our Common Home: Process-Relational Responses to Laudato Si’

About John B. Cobb Jr.

John B. Cobb, Jr., Ph.D, is a founding co-director of the Center for Process Studies and Process & Faith. He has held many positions, such as Ingraham Professor of Theology at the School of Theology at Claremont, Avery Professor at the Claremont Graduate School, Fullbright Professor at the University of Mainz, Visiting Professor at Vanderbilt, Harvard Divinity, Chicago Divinity Schools. His writings include: Christ in a Pluralistic Age; God and the World; For the Common Good. Co-winner of Grawemeyer Award of Ideas Improving World Order.