For decades the consensus of the psychedelic science community regarding bipolar disorder is that people with manic depression should avoid psychedelics as to not aggravate their condition.

They’re one of the few groups, along with those with a psychotic spectrum disorder or a heart condition, who are told sorry, psychedelics are not safe for them. In the case of those diagnosed with bipolar disorder, the fear is that the psychedelic experience can cause them to go manic, a state characterized by grandiose thinking and over-extending oneself (and often one’s bank account) that can lead to reckless, dangerous, and intrusive behavior that’s essentially out of character and can cause folks to lose control of their own lives or put themselves and possibly others in life-threatening situations.

And it’s not a myth, there are case studies, like this one from 1981, of people going manic during or after psychedelic experiences, but there haven’t been any trials controlling for things like the type of substance, set and setting, and dosage.

The Serotonergic System and Bipolar Disorder

Classic psychedelics and other medicines like MDMA work largely by affecting the brain’s serotonin system, especially the 5-HT2A receptor, says Will Barone, PsyD who’s worked in research and clinical settings with therapies involving MDMA, psilocybin, and ketamine. For most people, that’s not a huge risk. It’s not physically dangerous unless mixing different substances or taking super-high doses. But for people with bipolar disorder, the serotonergic activity may be what poses the problem – that increased activity could potentially trigger mania, or at least “increase the likelihood for mood episodes,” as Barone puts it.

Most bipolar people can’t even take SSRI anti-depressants without the risk of hypomania or a manic episode, and it’s how many of the folks I interviewed and who filled out a survey on bipolar and psychedelics I created got diagnosed in the first place. They went to their doctors feeling depressed, got prescribed an SSRI, and instead of feeling better (or nothing at all), they went manic, some even bordering or breaking through to psychosis. And so, to most in the psychedelic community that’s the end of the story. If an SSRI can cause mania, then surely it’s unsafe to give these folks psilocybin, MDMA, or ayahuasca, for example. Sorry bipolar diagnosed people, but you are excluded from the incredible and mystical insight, perspective shift and depression relief that psychedelics can grant others. But what if it’s not as open and shut as the community would make us think?

Before I dive any deeper into what I found investigating this subject, it’s important to say that I am in no way encouraging anyone to take psychedelics or get off their prescription medications. But living with bipolar disorder can be hard. Not only can mania be dangerous but the depression is also life-threatening; people with manic depression are much more likely to attempt and commit suicide than the general population. Yet, the hypersensitivity that is sometimes a handicap can also be a gift, one that many are unwilling to give up. And traditional pharmaceutical medication often suppresses empathy, creativity, spirituality, and concentration, among a host of other natural processes. So are there other options for folks living with this condition?

The Use of Ketamine for Bipolar Disorder

“Ketamine is the primary substance I would feel comfortable working with for a bipolar client,” says Barone. “It doesn’t seem to have the same risk for inducing a mood episode as MDMA or psilocybin.” He explains that ketamine doesn’t work nearly as much on serotonin as other entheogens, that instead, its primary action is on the glutamate and NMDA receptors, which has made many researchers theorize how ketamine produces its rapid antidepressant effects. “We’re still figuring out a lot about how ketamine works,” Barone explains, but the risk of inducing a manic episode from clinical ketamine treatment seems to be very low. “That’s one of the interesting things,” he says, “so far in clinical ketamine treatment, we haven’t seen mania develop in people with bipolar disorder, even with a history of mania. I haven’t personally seen any cases.” However, it’s important to note, many bipolar clients of Ketamine assisted therapy or infusions are also staying on their medications, likely mitigating the risk. “Ketamine is one of the only medications with psychedelic properties where it is appropriate for a patient to remain on their mood-stabilizing medications,” says Barone. “This is important for patients with bipolar disorder who can be destabilized by stopping medication too abruptly.”

In the program where Barone practices, Healing Realms Psychotherapy, clinicians sometimes utilize ketamine assisted psychotherapy (KAP) for individuals with bipolar disorder. It’s on a case by case basis, but essentially ketamine can be offered at different doses in conjunction with talk therapy, which can “use that psychedelic or altered experience to better understand your situation,” says Barone, “to have better awareness of your ego functioning and how to manage mood, in addition to the mood-stabilizing properties of ketamine.” Then, clinicians often increase the amount of follow-up sessions for bipolar clients to continue to monitor changes to mood or cognition, Barone tells me.

The Risks of Triggering Mania with Different Substances

A Ph.D. candidate at Flinders University, Benjamin Mudge, is looking into this phenomenon for his thesis and believes the type of substance plays a large role in mitigating the mania risk and providing the most balanced depression relief for those with manic depression. Mudge himself is bipolar, and at 48 has been through the wringer in attempts to treat his condition. Over a three hour Skype conversation, he tells me about being institutionalized and medicated on 17 different pharmaceuticals over 10 years with varying degrees of negative side effects, from weight gain and hair loss to losing his ability make art (a practice many thought he’d pursue professionally as a young person), capacity to make and perform music, and complete numbness to the rich world around him.

“I don’t feel suicidal, manic, or crazy [on the drugs the psychiatrists prescribed me],” Mudge explains. “But I don’t feel pleasure, fun, or arousal. I don’t feel a spiritual connection with nature. I can be sitting in a sacred ceremony, church, music festival, or forest, and everyone that’s around me is feeling something deep. But I just feel numb. And as a result of that, I then feel a sense of frustration and alienation from other people, and a sense of pointlessness.”

Eventually fed up, Mudge stopped taking pharmaceuticals cold-turkey (a practice he does not recommend to others) in search of a more natural remedy. After failed attempts with herbs like St John’s Wort, a friend asked if he had heard of ayahuasca. Now, 15 years later, Mudge drinks ayahuasca every couple of months to manage his condition (in addition to being careful with nutrition and avoiding other psychoactive substances) – and has never felt better. Even though, he tells me repeatedly throughout our conversation that this path isn’t for everyone and he in no way recommends folks stop taking their meds in favor of ayahuasca.

But his Ph.D. in psychiatry gives him the opportunity that many don’t have: he is systematically recording his moods and other reactions to ayahuasca, along with analyzing each tea he drinks in the lab to try and figure out the optimal brew for those living with manic depression. And he’s formulated a few fascinating theories that are catching the eye of psychedelic researchers around the globe.

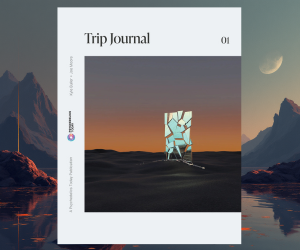

For one, substance matters, and Mudge believes DMT might hold the most benefits for those with bipolar disorder because of its incredibly short binding time to the 5-HT2A receptor. Most psychedelics “plug into” the 2A receptor, LSD, psilocybin, and DMT included, but the length to which they stay there determines the length of a trip. So for example, (see image 1) LSD stays plugged in for the longest, which explains why it’s such a longer-lasting trip than psilocybin or simply smoking pure DMT. But Mudge theorizes the binding time also matters when determining the mania risk for the bipolar brain, that the short binding time of DMT poses less of a risk of pushing bipolar people into mania, while substances that bind for longer, like LSD, present a higher risk.

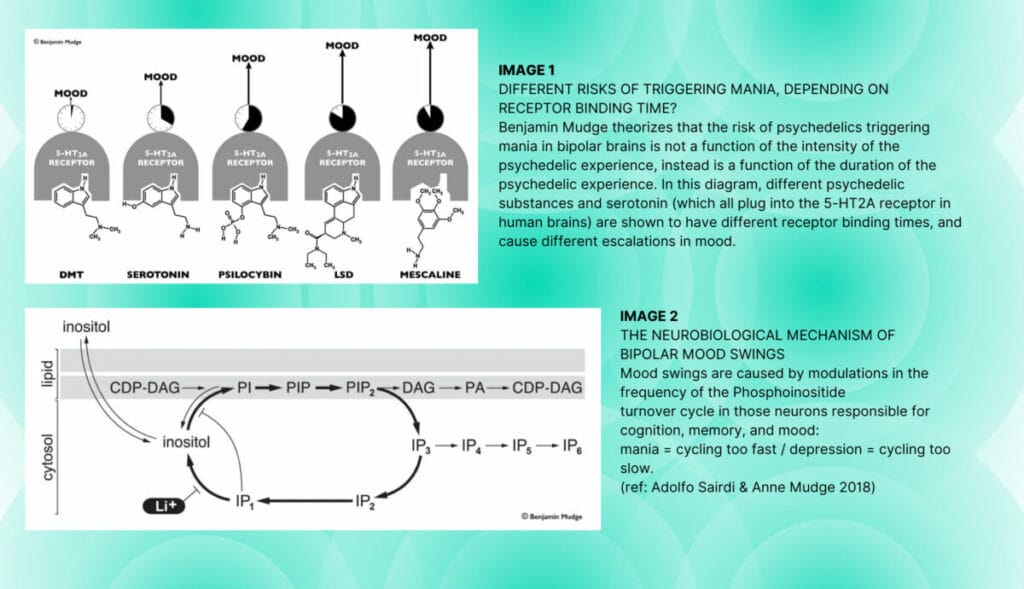

His theory gets more complicated than this and some of his mechanical ideas are based on findings of his mother, Anne W. Mudge, a Professor of neurobiology at University College London. In 2002 she discovered the bipolar brain has a malfunction in its inositol phosphate metabolism, which is a key regulating function that helps average folks regulate their moods, speed of their thoughts, and other related actions. In a nutshell, she discovered that instead of the bipolar mind being “too high” or “too low” (aka manic or depressive), that in reality, it was functioning at speeds that were too fast or too slow because of its missing regulating mechanism, thus explaining how medication like Lithium comes in to help regulate that speed (see image 2).

Now when we add serotonergic psychedelics or SSRI medication on top of a “dysregulated” brain, there’s a chance it could overextend itself and go too fast for too long, which could look like mania. And often, depression follows the mania in these cases, hence, the “disorderly” moods. However, this gets back to the binding time in Mudge’s theory, because what if shorter-acting psychedelics didn’t push people over the edge into mania, but rather, jump-started them out of depression and left them with more self-awareness to notice when their moods are fluctuating, giving them the ability to be more proactive in that process?

Mudge has found that ayahuasca and DMT help him the most (in carefully curated circumstances that we’ll discuss below). It brings him depression-relief and healing from a long list of past traumas, plus incredible awareness of the internal signs of a rising manic episode and how those behaviors have affected others. “One of the most fundamentally valuable things about ayahuasca for bipolar people is that it’s helped me understand how the manic episode is damaging people around me and damaging myself,” Mudge explains. “There is a sort of heightened sense of conscience, a social conscience that comes from the psychedelic awareness. That principle is perfect for getting bipolar people to understand how problematic the mania is, even if it feels amazing at the time.” And with the right brew of ayahuasca in a supportive container, this insight and healing come without pushing him into mania. He says after an ayahuasca ceremony he feels a “humble happiness” rather than a speedy or bordering on manic one.

Part of his research is interviewing others and collecting qualitative data of folks with bipolar disorder who use ayahuasca and DMT to try and determine what’s happening. And it’s beginning to prove his theories. For example, of the 10 bipolar people, he’s interviewed that smoke or vape pure DMT (without any MAOI inhibitor-containing plants or substances), “none of them went manic.” He says, “All of them reported the same thing, which was that it was mildly antidepressant. But it was also calming and grounding. As in, if they were on the manic end of the spectrum [which three were], it would bring them back to the center. And if they were depressed, it would bring them slightly up, but it wouldn’t keep pushing them and escalating into mania.”

This is a shocking finding, but not a surprising one. Psychedelics in the right dose and a prepared set and setting are known to give people a new perspective on their lives and behaviors, so why couldn’t they help folks increase their self-awareness around their mood? In a survey I conducted of bipolar diagnosed people who have tried psychedelics, I came to a similar finding. Of the 42 bipolar people who continue to use psychedelics like psilocybin, ayahuasca, DMT, mescaline and even LSD, 35 found the experience helped them manage their symptoms, including not only depression-relief but more awareness to ground themselves during mood shifts and ability to recognize manic behavior.

“I am aware of my manic episodes when they are taking place. I am also able to recognize them faster after they happen. Maybe I can’t change what I did in those moments, [but] I am able to hold compassion for myself and understand that I am still learning and growing because for so many years I just numbed myself with Pharma and alcohol,” described Mary* a 31-year-old with Bipolar I who no longer takes pharmaceutical medication but has been using psilocybin in varying doses since January 2019. “The manic events are shorter and less severe. For example, instead of spending $1,000 at a store, I’ll spend $100 and then recognize it and am able to hold compassion that I am making progress. (My manic episodes tend to lean towards over-spending, over-eating, over-everything). Also, it has helped my binging and purging, and my depression. Obviously, all are related, but I am just more aware of everything and also the plant medicine helps me see where everything is stemming from so I can re-parent those sides of myself.”

Interestingly, some who reported more awareness and ability to manage manic behaviors pointed to mania being a very “ego-driven” experience, perhaps explaining how psychedelics are helping folks deal with it rather than aggravate it further. “When I am starting towards a manic episode, psychedelics kind of smack me back down to earth and help me remember that I don’t have all my shit figured out. It humbles me and relieves the burning anger and irritation with compassion and connection to the ‘other’,” explained Sarah*, a 37-year-old with Bipolar 2 who is now off pharmaceuticals and instead uses psilocybin truffles about once a month in different doses, which are legal in the Netherlands where she lives.

Admittedly, the responses to the survey I created have a bias because most folks found the Google Form through my social media where I’m very pro-psychedelic (especially psilocybin mushrooms) and so my followers are more likely to report positive experiences than negative ones. However, considering the lack of options beyond lifelong medication for the bipolar population, it’s an interesting finding in need of more investigation beyond anecdotal reports. Could one psychedelic experience every few months “ground” bipolar folks, allowing them to experience and manage their full range of feelings without heavy meds like Lithium? Even in Barone’s practice with ketamine, he tells Psychedelics Today that when appropriate, the goal is to wean some patients off their pharmaceutical medications eventually and instead, manage their moods with the help of intermittent ketamine-assisted therapy sessions and building skills to independently manage mood fluctuations.

It’s super controversial, especially considering unmedicated bipolar folks are at a much higher risk for suicide. Plus, going off psychiatric medication quickly without a doctor’s supervision is also dangerous, especially when combined with psychedelics. Barone, who’s volunteered at Burning Man’s Zendo Project for seven years and supervised for four, explains the combination of stopping medication to take psychedelics has caused numerous attendees to have a psychotic break at Black Rock City. Plus, Barone says that for some people, “It may be the intensity of the experience or having insufficient support during and after a trip that shifts mood or cognitive process beyond the effects of the substance.”

At the same time, mixing bipolar medications with psychedelics seems to be contraindicated, although getting a clear answer from doctors on this is hard. While it’s pretty common knowledge that SSRI’s shouldn’t be combined with psychedelics for several reasons, including the potential risk of Serotonin Syndrome, there’s less info out there about common bipolar medications like lamotrigine and lithium. Some doctors, like a psychiatrist Mudge, knows of in New York and those I interviewed for my book on mushrooms, seem to think lamotrigine doesn’t pose a huge risk when mixing with psilocybin or ayahuasca, however, lithium seems to be in a class of its own. I’ve personally heard of two instances where lithium mixed with LSD caused such negative reactions (including a seizure) that both people were sent to the emergency room to the despair of their tripping friends. There’s more info on mixing Lithium and LSD in this Erowid vault.

To make matters even more complicated, even some of those who responded to my survey saying psychedelics help them reflect on their manic/hypomanic behaviors and ground themselves often also describe a singular incident where they did go manic and even psychotic or deeply paranoid after particular psychedelic journeys where they either “took too much,” had a “bad trip”, or took substances in less than ideal set and settings. Which brings us back to Mudge’s theories, that the bipolar brain is more sensitive and can’t handle certain substances or situations, like frequent psychedelic use or poly-drug mixes, without possibly heading into mania.

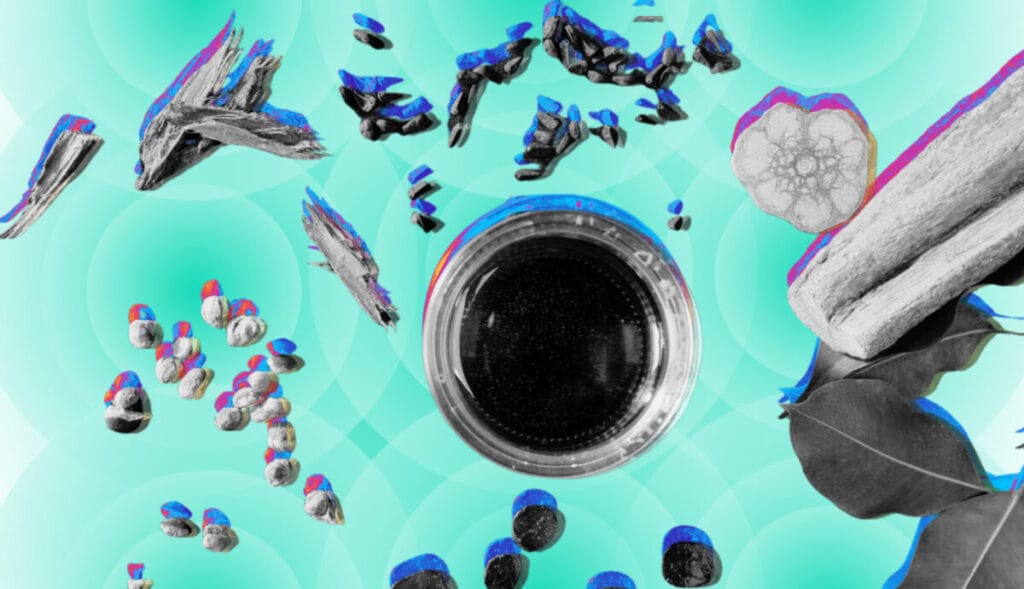

And so, Mudge has created harm reduction guidelines for bipolar diagnosed people who want to drink ayahuasca, although he tells me multiple times he is not advising anyone to take ayahuasca or do anything illegal, but instead to please wait until his research and other community initiatives are completed. Yet, if people ignore his advice, the guidelines (see image 3) do provide a lot of interesting information to reduce harm and the risk of mood episodes. For instance, while the ayahuasca tradition is to partake in multiple ceremonies over a week or two, Mudge says that puts the bipolar brain at a much higher risk for mania. Instead, participating in one ceremony and getting enough sleep afterward will provide folks with a lot more benefits than continuing to drink – and stimulate their 5-HT2A receptors – night after night.

Plus, he’s seen this high frequency of psychedelic use play out badly with other substances as well in his interview subjects, even at microdoses. For example, he tells me of a bipolar man who was microdosing psilocybin every day to manage his mood and had the worst manic episode of his life – at 40. Mudge believes it was the repeated stimulation of taking a serotonergic substance that binds for six hours that induced mania – similar to what an SSRI would do to a bipolar person.

When it comes to safe ayahuasca practices for those diagnosed with manic depression, Mudge believes mixing with other substances – even if they’re presented in ceremony as holy tools, like rapé, cannabis and even cacao or chocolate – poses a higher risk for pushing the bipolar brain into mania. I ask if there should be a specific bipolar “dieta” (a concept in the ayahuasca tradition where you adhere to a special diet in preparation for your ceremony) and he says absolutely. “This is why you’re not supposed to eat overripe bananas and soy sauce. Because it’s chemically reactive,” Mudge explains, and for bipolar folks, the dieta will have to be even more restrictive to provide the maximum benefits and the least amount of harm.

Lastly, when it comes to ayahuasca, not all brews are created equally, and Mudge also believes some brews that pose a higher risk than others based on their chemical composition. For example, ayahuasca prepared in the Amazon jungle can have a different combination of herbs and precise species of vine depending on the shaman, culture, and retreat center. While most psychedelics have a single type of molecule causing the experience, there are at least four psychoactive ingredients in ayahuasca: harmine, harmaline, tetrahydroharmine, and DMT. Therefore, brews can have different ratios of MAOI inhibitors to DMT molecules, and Mudge believes the bipolar brain responds better to a brew that has more DMT because the MAOI inhibitors can push people into mania (just like MAOI pharmaceuticals are known to do). He also says ayahuasca prepared in other parts of the world that use Syrian Rue instead of the ayahuasca vine also poses more of a risk because it has a different ratio of harmala alkaloids than the Banisteriopsis caapi vine used in genuine ayahuasca.

Plus, lots of the ayahuasca that is consumed isn’t brewed fresh, but brewed once and is carried around for months to over a year, and in that time it begins to ferment and produce alcohol. And Mudge believes fermented ayahuasca poses a problem for the bipolar brain where a depressive hangover can follow rather than a humble afterglow. “I think it changes the qualitative experience for everybody,” he elaborates. “I think it makes the ceremony more intense, more into the shadow.” But for the bipolar brain, “which is more sensitive” it can leave people feeling agitated and depressed. He explains there is a trick to getting rid of the alcohol in aged ayahuasca, basically cooking the brew on a very low heat for 10 to 20 minutes so that it steams the alcohol off but never starts to boil or even simmer. “It should start to smell like a vegetable soup when it’s ready,” Mudge says.

And it’s not like bipolar people don’t ever go manic after drinking ayahuasca, it happens, and 17 of his 62 interview subjects experienced it. But, after investigating each situation further, it seems many, if not all, of the 17 were mixing substances, drinking fermented ayahuasca or brews with Syrian Rue and participating in multiple ceremonies in a week, and so in terms of his research, are technically false negatives. Although, these situations only further prove the need for his research and more like it.

Clinical Perspectives and Safety Concerns

But what about other psychedelic substances? If Mudge’s theory is correct, is DMT the only option that’s less likely to cause mania? What about mushrooms, LSD, or MDMA? Could they all have a place with specific safety guidelines? And what would those guidelines look like for a person diagnosed with manic depression? Cynthia*, a clinical therapist specializing in spiritual emergence and psychedelic integration who was trained in the transpersonal paradigm at the California Institute for Integral Studies (CIIS), thinks bipolar clients not only need a lot of preparation and integration support for a psychedelic experience, like with a professional therapist or spiritual guide, but they need to be able to sustain their stability without medication first, which she realizes just isn’t possible for everyone. She’s come to this belief not only as a clinician but as someone who was diagnosed with bipolar herself over 20 years ago, although she doesn’t identify very strongly with the diagnosis.

She views bipolar, and all mental illness, through a very spiritual lens. “It’s not just our biochemistry and our diagnostic criteria, but it’s really our souls,” she says. She tells me about her only manic-psychotic episode which was brought on by SSRI medication in the late 1990s when she was only 20 years old. “It absolutely was also a very spiritual experience and very much a healing crisis.” She explains, during her episode, she had trauma from her early childhood come up and other painful material that needs resolving, but she didn’t get the support to really examine it until years later. I ask her if she thinks mania can be thought of in terms of Stanislav and Christina Grof’s idea of “Spiritual Emergence(y)”, a theory that views some non-ordinary states of consciousness as healing processes that could be supported for the most positive gain rather than suppressed with tranquilizing medication.

“I do think mine was a spiritual emergence. And I knew that at the time, but I didn’t have the language for it,” she says. “And what I’ve come to conclude is I think it’s not necessarily a completely ‘either-or’. I think there’s both, or it’s almost like two different languages used to describe a similar thing. Because, if you go through the checklist, I definitely fit the criteria for manic psychosis. And I definitely was having trouble, just at the very end, not eating and sleeping and not being able to use words, things that were dangerous. Now, if I had had sitters and 24 hours of support and a bunch of space to wander around, I probably could have rode it out and had the support to just be in that state faithfully until it ran its course. But I didn’t, and most of us don’t.”

It’s a curious and radical idea that insight and healing can come from some natural non-ordinary states of consciousness, like mania and psychosis, if they could be “sat with” and supported as they played out, just like a psychedelic trip. And it’s not the first similarity between manic depression and the psychedelic experience that I came across researching this piece. Two other bipolar diagnosed people I spoke to pointed to mania being very much like a entheogenic journey. “So much of my mania feels like tripping,” said Pam* a 39-year-old woman with Bipolar 1 who no longer takes prescription mood stabilizers but uses different psychedelics to deal with her depression, “If the tripping will end, so will the mania.”

However, in our society, we very much view these states as needing to be “cured” and suppressed rather than explored and supported. And in Cynthia’s case, she ended up in a psychiatric hospital and then on Lithium for five years after her episode. But during her first semester of grad school at CIIS, she began working with a holistic psychiatrist, part of the Grofs’ Spiritual Emergence Network, who helped her confront her trauma, wean off the medication, and learn to feel and manage the full range of her emotions through the use of spiritual and Eastern practices. Which admittedly, right after years of Lithium, was hard. She essentially had to relearn how to feel and it was overwhelming at first. “And then I was terrified of doing anything spiritual. I was terrified to meditate. I had a chance to do holotropic breathwork and I was like, I don’t want to rock the boat.” But she did learn and developed other spiritual practices, like yoga, which helped her understand how to regulate her own energy. And, even though she’s not currently on daily pharmaceuticals, she definitely still thinks they have a place, like to regulate mood for a shorter time and to control “breakout” symptoms of mania, such as trouble sleeping.

Implications for Future Research and Guidelines

For Cynthia, psychedelics were not part of this re-learning for 20 years. Instead, she spent that time integrating her spiritual emergence/manic episode, learning how to recognize the “edges” of hypomania and ground herself naturally. But two years ago, she finally felt ready to go back into the psychedelic space with spiritual guides, and now she manages all types of psychedelic experiences, even the ones Mudge warns against like LSD, MDMA, 2C-B and others I had to look up like 3-MMC and 2C-E. She says it’s not the psychedelics that keep her grounded like some of my survey participants reported, but since she’s learned how to ground herself, these experiences are manageable and beneficial for other healing.

“I’ve had a lot of stuff come up from around my episode, like fear of my own greatness. It’s like I’m scared to go visionary because they’re going to label me as manic. But I had to reclaim my comfort with that.” Cynthia admits, after a trip, especially with “heart medicines” like MDMA, she does have increased energy, “It’s exciting, I have this sort of energy of how wonderful everything is. I just have to make sure I’m sleeping and intentionally doing things to stay grounded.” She says there was a time recently where she was taking empathogens a little too often – once a month, sometimes more – and she started to have “more depressive dips and more anxiety.” But she was able to recognize that and back off. “Now I’m trying to keep it like once a quarter or even less than that.”

However, she says as a clinician, “I don’t feel super comfortable if I had a bipolar client doing classic psychedelics. I might, but it would be very case by case because I do think there is that potential risk.” She also believes bipolar to be a spectrum, and those with more severe cases with recurrent manic episodes might not be able to stabilize themselves like she’s learned to. But the connection between spiritual emergence and bipolar disorder, psychedelics and mania seem too close and full of such vast potential to not be investigated further. And of course, Mudge has a plan for how to proceed.

Once Mudge figures out the ideal recipe for brewing ayahuasca “in a balanced way” that is medicinal but “not dangerous in terms of triggering mania,” his mission is to create the “Manic Depressive Community Church”. It would serve as a community for those with bipolar and those affected by the condition (like parents and spouses) where ayahuasca, served in the safest possible way by understanding facilitators who are bipolar themselves, is the sacrament. His vision is that this church would be a non-profit organization that’s local to people so they wouldn’t have to travel to the Amazon to take this medicine. And of course, being the academic that he is, he also envisions setting up a clinical trial or having the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS) come in to do an observational clinical trial so the community can finally get some hard data on this population other than assumptions, anecdotes, and old case studies.

Mudge also insists that bipolar folks wait for him to accomplish this goal before they start drinking ayahuasca or taking other kinds of psychedelics. He says his safety protocol and recipe are still about two years away from being complete, and in the meantime, he encourages folks to prepare by getting their lifestyles in order. He explains that it means accepting their diagnosis and getting on medications that work, like lamotrigine and a low dose of lithium. It also means getting enough sleep and stopping other recreational or self-medicating drug use like alcohol, cannabis, or whatever else. “That’ll help you in the next year or two in a massive way,” says Mudge, “and then you’ll be ready to drink safely.”

But the weight of the bipolar community’s desire to heal shouldn’t be all up to one man. The psychedelic science community should also step up and start investigating the potential benefits and harms for this large and desperate population. “There’s a massive potential of psychedelics, but bipolar people have unique brain chemistry,” says Mudge. “They need the psychedelic experience to be chemically tailored to their brains’ needs.”

*Editor’s note: Names changed for privacy.