There are a great many tales to be told about the countercultural years of the 1960s, but the story of tripping Rabbis whose psychedelic exploration contributed to a great Jewish Renewal isn’t found in many history books.

While the world was shaken by the Vietnam War and the ongoing Cold War, the counterculture represented a rise of a new consciousness expressed in forms of music, art, drugs, and civil disobedience. In a collective rise against the ‘American dream’ utopia built by their parents, the young generation sought to find alternatives to materialist and conservative values. For them, the counterculture was a strike of anti-establishment, in an egalitarian spirit emphasizing the value of human relationships and the individual’s quest for meaning in life.

Drugs like LSD, cannabis, and mescaline became increasingly common with renowned academics, authors and poets of the era. But they weren’t the only cultural leaders exploring the power of mind-altering substances; while the world watched Timothy Leary, Richard Alpert (later known as Ram Dass), Aldous Huxley, and Allen Ginsberg encourage the new generation to turn on, tune in, and drop out, a few radical rabbis were quietly exploring the use of psychedelics to get closer to God, and revive age-old mystical traditions.

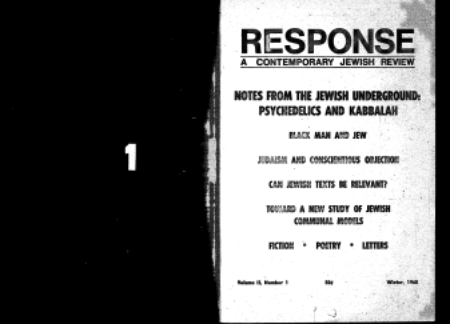

I was inspired to investigate the connection between liberal Jewish movements and psychedelics after encountering the article ‘Psychedelics and Kabbalah,’published in the Jewish youth magazine Response (1968) by Itzik Lodzer. Lodzer was revealed to be a pseudonym for Arthur Green, the now well-established Jewish scholar, rabbi, and influential figure in the establishment of liberal Jewish practices (for the remainder of this article, Lodzer will be referred to as Arthur Green). One of Green’s contributions was Havurat Shalom, an experimental community embracing Jewish libertarianism and alternative religious values. Through Havurat Shalom, Green met another unconventional rabbi: Zalman Schachter-Shalomi, now also commonly referred to as ‘Reb Zalman,’ founder of the Jewish Renewal movement. Schachter-Shalomi became the leading figure for the Jewish liberation theology, and his influence for the entire Jewish community is monumental.

Both Green and Schachter-Shalomi referred to psychedelics as tools to shed light onto forgotten mystical traditions. The Jewish Renewal movement was an epiphany of that realization, and strove to reinvigorate stagnant traditions by reinventing modern Judaism through Kabbalistic, Hasidic, and musical practices. The lives of these two rabbis, their encounters with psychedelic drugs, and the paths these experiences led them on, are remarkable examples of how psychedelic drugs were an integral part of reinventing Jewish theology.

From their stories we can conjecture that psychedelics were a factor in influencing certain powerful, liberal Jewish ideologies, as well as helping their users to experience Jewish mystical theology in a new light.

The Psychedelic Experience and the Kabbalah

Kabbalah is Hebrew for ‘receiving’. It encompasses a set of teachings generally distinguished from the ‘traditional’ Jewish doctrine. The term came into use in 13th century Spain, where a group of Jewish esoterics and mystics began to separate themselves from the regular Jewish practitioners. To this day, hundreds of modern Kabbalah centers have opened up all around the United States and Europe and many well-known celebrities with (and without) Jewish heritage have picked up the practice of this mystical tradition.

In the 1968 Jewish Review Response, Green draws a parallel between his psychedelic experience and the teachings of the Kabbalah. For him, the foundation of the Kabbalist teachings became vividly real during his encounter with LSD. This is also the likely reason why he chose to write about a topic which, even during the period when LSD was legal, was considered contentious for the traditional Jewish community. Green analyzed parts of the psychedelic experience corresponding to Kabbalist teachings. Many of the elements recognized today as classic psychedelic trip experiences, represented vivid manifestations of Green’s own belief system.

Re-Evaluating Perspective on Psychedelics

The first aspect Green considered a mystical experience is the notion of perspective.

“That which I thought was all terribly real just a few seconds ago now seems to be a part of a great dramatic role-playing situation, a cosmic comedy which this ‘me’ has to play out for the benefit of the audience,” he said.

In Kabbalah the only ‘true’ unchanging reality is the Ein Sof, ‘the Upper Reality,’ our ways of perceiving that reality are under constant change. For Green, psychedelics opened the illusionary nature of unchanging reality and of his own self. He wrote: “Seen from beyond, however, world and ego are but aspects of the same illusion. From God’s point of view, only God can be real.”

The Paradox of Change

The second aspect Green brought forth is the paradox of the fundamental change of everything about God, the simultaneous fundamental constancy of God, and the circular coexistence of impermanence and permanence: “All is becoming moving. I blink my eyes and seem to reopen them to an entirely new universe. One terribly different from that which existed a moment ago […] If there is a ‘God’ we have discovered through psychedelics, He is the One within the many; the changeless constant in a world of change.”

God’s Gender – Maybe Not Male After All?

Having strongly experienced a feminine presence during his trip, Green questioned the prevailing Judeo-Christian assumptions of God as male, underlying that ‘the father of the heavens’ only makes sense in a context where there is also ‘the mother.’ He argued that Judaism today has become trapped by the stationary image of God as a father figure. Subsequently, the Jewish Renewal movement has been especially focused on the revival of the female Goddess. For Green, the two sides of God were as attainable for ‘contemporary trippers,’ as they had been for the mystics of the past.

Discovering God’s Fluid Essence

Typically, descriptions of divinity in Kabbalistic writings are inconsistent and fully metaphorical. Green observed the parallel of the flow of beautiful images during his trip and the fluid Kabbalist descriptions of the nature of divinity, but warned against any static statements defining God. He argued that only symbolic and metaphorical descriptions could come close to the truth. Although the process in which the voyager creates a metaphor to describe the flow of images and information can be enjoyable, he warned against taking one’s own imagery too seriously:

“Indeed, this is one of the great ‘pastime’ of people under the influence of psychedelics: the construction of elaborate and often beautiful systems of imagery which momentarily seem to contain all the meaning of life or the secrets of all the universe, only to push beyond them moments later, leaving their remains as desolate as the ruins of a child’s castle in the sand. No metaphor is permanent, one can always ascend another rung and look down on the silliness of what appeared to be a revelation just minutes before.”

Exploring God’s Authentic Nature

What Green referred to as the “deepest, simplest and most radical insight of the psychedelic consciousness” concerns the authentic nature of God. He wrote: “This insight has been so terribly frightening to the Jewish consciousness, so bizarre in terms of the biblical background of all Jewish faith, that even the mystics who knew it well, generally fled from fully spelling it out.” All reality is at one with the Divine, and therefore every human, Jewish or not, is a part of God’s divine nature, he posited. According to Green, the very sanity of the Western civilization lies in the ability to distinguish fantasy from reality, to separate between God and humans. Now that this fantasy had been shattered for the young Green, the rest of his life was bound to change. “If God and man are truly one … what has all the game been for?” he questioned.

Green’s testimony of his first psychedelic voyage is a remarkable historical account of how psychedelics can operate on the consciousness of a deeply religious individual. Green’s understanding of Kabbalah provided a strong framework through which the experience could fluidly mature, and although he voiced his concerns of autonomous explorations of God through psychopharmacology, he also believed both the psychedelic and mystical consciousness can be compatible.

In his 2016 biography, Hasidism for Tomorrow, he still states that taking LSD was an important step for his understanding of Hasidic and Kabbalistic philosophies. Such states would be achievable without the substances, he says, but acknowledges taking drugs and spontaneous mystical experiences as parallel processes.

The question arises: will the revolutionary qualities of the Jewish Renewal movement prove lasting, or will Judaism shake off Liberal influences and continue its static path? Just as the Jewish Renewal movement is often seen as a minor influence on a small current, the counterculture movement is often viewed as a failed attempt of revolution, as utopia slowly sinking into disappointment. Both Green and Schachter-Shalomi held their experiences with psychedelics as major influential points in their lives. As the research on psychedelic drugs and neurotheology continues to advance, perhaps the liberation theologies of a number of religions can be understood in a completely novel way.

According to Shalom Goldman, a professor of religion and Middle Eastern studies, the impact of the Jewish Renewal movement has left a permanent mark on contemporary Jewish life.

“Schachter-Shalomi’s Jewish Renewal still remains small in comparison to the larger Jewish denominations, but its influence is wide,” he said. “And many of those influenced would be quite surprised to read that in a way, it started with LSD.”

Editor’s note: this article is an adapted version of the essay, Tripping Rabbis: The Impact of Psychedelic Consciousness in the Revival of Jewish Mystical Tradition during the 1960s Counterculture Movement, by Johanna Hilla-Maria Sopanen, originally published in Psychedelic Press Volume XXI (2017).