By Jeff Kronenfeld

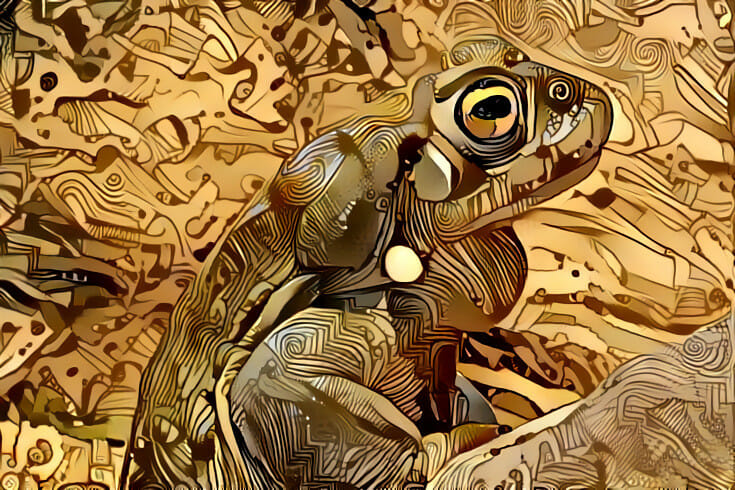

Sonoran Desert toads emerge from earthly tombs every year after the late summer monsoons roll in, which cause countless tiny ponds and lakes to form. Though most will evaporate in a few hours or days, toads lay eggs in the depths of these small water beds. Most of the tadpoles won’t last longer than the waters in which they are born, a few will become pollywogs then toads, ensuring survival for another generation.

Life in the desert is stark as it is. But these unique desert toads are currently facing a host of new threats, including climate change, habitat loss and — perhaps most dangerous — commodification. Bufo alvarius, the Sonoran Desert toad’s scientific name, is the only known animal source of 5-MeO-DMT, a popular chemical among psychedelic users. Unfortunately, poachers overharvest toads to feed the ever-growing market for this powerful substance. While the International Union for Conservation of Nature Red List of Threatened Species placed these toads in the lowest category of risk for extinction in 2004, the same report acknowledged they were virtually extinct in California. Scientists, conservationists, and artists are banding together to ensure the rest of the species avoids a similar fate.

Climate Change on Habitats

To understand how human-caused climate change could impact Sonoran Desert toads, we first need to look at potential effects on their home region. A 2012 study by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) predicted that the Southwest would continue to get hotter and drier. A 2018 National Climate Assessment bore out those predictions. This is bad news for toads, who already live near their physiological limits. More troubling was a 2017 report in Nature Climate Change, which predicted the probable decline of monsoons by 30 to 40 percent over the next century.

Thomas R. Jones, Amphibians and Reptiles Program Manager for the Arizona Game and Fish Department, believes parsing the impact of climate change from other threats and historical fluctuations is difficult if not impossible. This past summer he observed a decrease in toad populations at a site where they are normally abundant. “I think it’s a reasonable assumption to say if the monsoon gets squirrely and we have drier years, it will be rougher on summer breeding anurans — toads and frogs — like the Sonoran Desert toad,” Jones said.

Overdevelopment and the Destruction of Habitats

While climate change looms like ominous clouds in the distance, habitat loss is the single greatest threat to Sonoran Desert toads. According to a 2013 report from the USDA, 90 percent of riparian areas in Arizona and New Mexico converted to other land uses over the last century, ultimately turning habitats into agriculture fields or residential developments. At the same time, surface water was diverted from the few year-round rivers into massive reservoirs as aquifers pumped out groundwater in order to supply the region’s growing population and agricultural production.

These toads once thrived in farmland irrigation systems, too. But, due to the increasingly intense use of chemicals — both pesticides and fertilizers — and mechanization, they disappeared from some agriculture areas, such as the Southern California side of the Colorado River and the Imperial Valley.

Paved roads are also particularly deadly to these creatures. Toads go to pools that form on impermeable surfaces where water can more easily absorb through their skin. The hot spots for Sonoran Desert toads are lined with roads, often putting them in harm’s way. In fact, a 2010 study in Human-Wildlife Interactions estimated 12,264 amphibians died annually on roads in and around Saguaro National Park just west of Tucson, Arizona. Roads also hinder the toad’s range, causing a loss in gene flow, or genetic evolution, which negatively effects populations, according to Jones. “The number of animals that die on roads are just huge.”

Pop Culture, Money, and Psychedelic Tourism

The least understood threat is the impact of poaching and overharvesting for the 5-MeO-DMT market. Though Sonoran Desert toads can be legally gathered with appropriate licenses in Arizona, collecting them for the extraction of 5-MeO-DMT — which became a Schedule 1 substance in 2011 — is a federal crime.

In order to extract 5MeO-DMT, the toads must be agitated, which causes their glands to excrete poison. Then, it’s squeezed or scraped out. Robert Villa, president of the Tucson Herpetological Society (THS) and a research associate at the University of Arizona’s Desert Laboratory on Tumamoc Hill, is concerned about the harm this poses to toad survival.

“I think what’s going to happen over time is that if intensive collection continues,” Villa explained, “it’s going to create a vacuum in these areas, what is also known as a mortality sink.”

Some argue that indigenous communities have used the drug for centuries. But Villa points to flaws in this argument, saying that some advancing this position may have a vested financial interest in doing so. Some scholars have cited the discovery of toad bones at shamanic burial sites. If true, it could legitimize the toad extraction industry, helping businesses grow at the expense of the toad populations. For doctors or others selling 5-MeO-DMT, this would be a boon.

But Villa noted the bones were from a different species of toad that doesn’t produce 5-MeO-DMT. He is not convinced by the evidence that indigenous people historically used the toad as a source of 5-MeO-DMT. “We couldn’t decipher it from residues. There’s research that discovered cacao residue in pots in New Mexico,” Villa explained. “What we see today is a blatant misuse of indigenous culture to do it.”

We may never know who first smoked 5-MeO-DMT for sure, but one of the earliest academic papers citing its psychedelic properties appeared in a 1967 issue of Biochemical Pharmacology. Then, knowledge about how to extract, prepare, and consume 5-MeO-DMT from toads was first widely propagated by a pamphlet written in 1983. The document contained detailed instructions, diagrams, and background information. Its author was listed as Albert Most, a pen name, though multiple people throughout history have claimed to be Most.

In a 2017 episode of VICE’s Hamilton’s Pharmacopeia, a man named Alfred Savinelli claimed he wrote the pamphlet and that he was the first person to ever consume the toad’s venom. Savinelli is the author of Plants of Power: Native American Ceremony and the Use of Sacred Plants, but aside from that his claims have not been verified.

Though its authorship is disputed, the pamphlet’s role in raising awareness about the drug is not. Following its publication, groups like the Church of the Toad of Light started promoting 5-MeO-DMT consumption. Its proponents claim the drug can help with depression and anxiety, which was supported by a study in The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse earlier this year. Advocates also claim it helps with recovery from substance abuse.

Unfortunately, a number of bad actors are harming toads and humans by providing the toad excrement for consumption. An open letter published earlier this year accused two doctors who facilitate 5-MeO-DMT use, Octavio Rettig and Gerry Sandoval, of defrauding, harming, and even causing patients to die. Numerous self-proclaimed shamans administer the drug illegally throughout the US and other countries. One such person was identified as Shaman Dan. He is alleged to have led a series of 5-MeO-DMT parties at the residence of a woman in Southern California, who we’ll call Christina (not her real name) for the sake of anonymity.

Christina was connected to Shaman Dan by her mentors, who recruited her into Amway, a multi-level marketing company accused of being a pyramid scheme by consumer advocates, academics, and newspapers such as the New York Times and the Wall Street Journal. She described Shaman Dan as a white male under 25-years-old who formerly sold energy drinks through a multi-level marketing company. He told Christina that he was trained in Mexico by a woman named Shaman Sandra. After extracting the toad’s poison — which Christina incorrectly identified as venom — Shaman Dan described using an undisclosed chemical as a bonding agent into the 5 MeO-DMT blend.

“It’s not something the individual taking it knows,” Christina said. “That’s why it’s very important that you trust whoever is administering this, because if they do not know what they’re doing, they will mess you up. It’s basically like taking crystal meth from a drug dealer off the street.”

Public awareness of the toad has grown rapidly in recent years, with increasing references not just in academic journals, but in popular media as well. Journalist and author Michael Pollan discussed his negative experience with 5-MeO-DMT in his 2018 book How to Change Your Mind, which reached number one on the New York Times bestsellers list. Pollan also discussed the subject on The Joe Rogan Experience, a popular podcast. Host Joe Rogan has covered 5-MeO-DMTs transformative power many times, perhaps most notably in an episode from earlier this year with Mike Tyson. All this buzz leaves the little toads facing evermore heavyweight dangers from all corners.

The Sonoran Desert toad does not face these challenges alone, however. The THS is funding a project to study how the ionic composition of cement water holes may be harmful or even lethal to amphibians. Villa partnered with Cream Design and Print to produce t-shirts, posters and other items that spread awareness about the danger extraction poses to toads, and to raise money for conservation efforts. He hopes that if potential 5-MeO-DMT users know the harm they’re doing to these hardy animals, that they will choose less-harmful methods for obtaining whatever it is they seek.

While the toad may be the only animal source for 5-MeO-DMT, the compound can be synthesized and found in many plants. The seeds of one species of Anadenanthera trees in South America contain 5-MeO-DMT and DMT. Virola trees also originate from South America, and some species of this plant contain both forms of DMT as well. They are both typically prepared as snuffs but can be consumed otherways as well.

Synthetic 5-MeO-DMT is in many ways a superior delivery vehicle to the toad-sourced variety. The extract from toads contains many other chemicals and can be dangerous if it is not consumed correctly. Synthetic 5-MeO-DMT can be precisely dosed, whereas every toad’s extract is a little different. The study cited earlier showing 5-MeO-DMT’s effectiveness as a treatment for depression and anxiety used the synthetic variety in its experimental trials.

The benefits of synthetic versus toad-sourced 5-MeO-DMT were even discussed by Rogan on his podcast. Rogan reported a very positive experience when he consumed synthetic 5-MeO-DMT. Pollan had a very different reaction, describing his consumption of the toad-sourced variety as horrible. For the most toad-loving psychonauts, these alternatives can provide a safer and more eco-conscious way to experience this unique molecule. “It boils down to your individual ethics,” Villa said. “As psychonauts, I would hope that you are able to think about how your use of substances and your acquisition of those substances has an effect on the rest of the world.”

About the Author

Jeff Kronenfeld is an independent journalist and fiction writer based out of Phoenix, Arizona. His articles have been published in Vice, Overture Global Magazine and other outlets. His fiction has been published by the Kurt Vonnegut Memorial Library, Four Chambers Press and other presses. For more info, go to www.jeff-k.com.

Instagram: jeff.the.scrivener