I was taught to identify and locate the Psilocybe semilanceata mushroom, or Liberty Cap, as a teenager around the turn of the millennium. In those days in Britain it was common knowledge passed down from older people and shared amongst groups of curious friends. Had I needed a guidebook though, they were certainly available, and I was only ever a few internet clicks away from accurate information. Moreover, if they remained fresh and unprocessed, it was perfectly legal for me to possess them.

Within a few years, it was equally possible for me, or anyone else throughout Britain, to enter a headshop in any season to procure some exotic varieties of Psilocybe cubensis without waiting for autumn to come around to pick native Liberty Caps. This, my friends and I did regularly. Walks in nature, free parties, garden gatherings, candlelit bedroom vigils—many occasions were enriched by them. In 2005, after decades of ambiguity, the legal sale and possession of fresh magic mushrooms was brought to an end by the New Labour government.

At the time of writing, it has now been twenty years since the law changed. The pharmacratic web of legislation, courts, medicine, and policing is, if anything, even more complicated than it was then. While some areas, notably scientific research, have become more prominent, and policing apparently less concerned with (some) drug offences, the fact remains that both picking and growing Psilocybe mushrooms remains illegal in Britain. Cases can and do get brought to court. My book, Psilocybe Pickers, is about how we find ourselves in this position today.

Psilocybe Pickers began life as just a short article. Having many years ago read Andy Letcher’s quite brilliant Shroom (2006), I wanted to explore in more detail some of the areas he described, particularly around the earliest British court cases (of which Andy necessarily only touches upon in his internationally-focused work). The hindsight that a couple of decades brings is useful, and fortunately access to sources—especially local newspapers—has greatly improved, so I am able to tell a more thorough story.

Another reason to undertake the writing of this history is in order to demonstrate that there have been at least four generations of Britons picking Liberty Caps. It is, by any sensible estimate, now something of a tradition—it has a lineage. Furthermore this is not only within any self-described countercultural movement (of which several have enjoyed being bemushroomed) but also within local, regional communities too. Here, it is a kind of rite of passage. Recreational and hedonistic to be sure but nonetheless sacred so far as local community matters.

Most of the stories and adventures that bemushroomed Britons have experienced are perished, forgotten, or kept private. This is perhaps how it should be. It is certainly a central facet of the psychedelic experience. Something inwardly profound that only reveals itself though cultural waves. Yet, this does not make the work of a historian very easy. Therefore, where I have found recollections, I have tended to include them in the book, however brief.

It is with unnamed teenagers that one finds the humour and the mischief of Liberty Cap culture. For example, when one 15-year-old was pushed by a journalist on the negative effects of mushroom tripping, they replied, ‘The only bad effect you get is backache from picking them’. Or, another, when asked why they ate mushrooms, replying, ‘You have to get your kicks somehow’. Against the very serious medical establishment warnings, it is possible to discern the playful reality of most bemushroomed people.

Therefore, through newspaper reports, archival material, interviews and published papers, I have focused on the regional and legal contexts of the Psilocybe pickers in order to tease out the way in which magic mushrooms seeded in British society, and how the Establishment reacted. Indeed, this story cannot be told without also considering scientific research, both psychiatric and mycological, alongside the extraordinary lengths the authorities went to in order to stamp out the nascent mushroom-using culture.

From book banning, court test cases on the meaning of ‘preparation’ and widespread police co-ordination, the authorities tried numerous methods to supress magic mushroom picking. Yet, in the end, it was not the field pickers that caused the eventual change in the law in 2005. Instead, it was the growth of people using mushroom grow kits, which I trace from the late 1970s, which eventually burgeoned into a vast importing/exporting business supplying Psilocybe mushrooms in head shops of Britain and Europe, particularly the Netherlands.

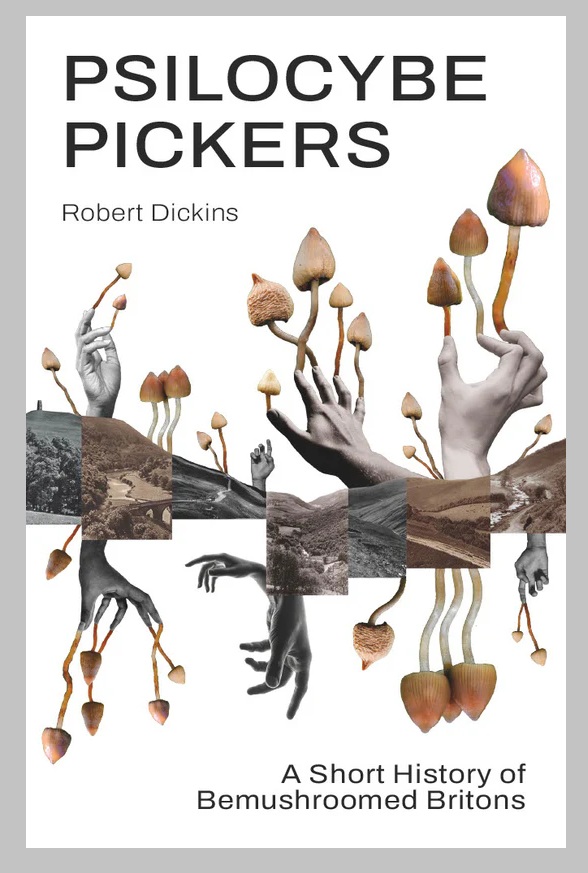

Psilocybe Pickers tell the story of how a culture that started life in the shadows slowly blossomed in every corner of Britain’s landscape, transforming into a staple part of recreational, regional drug scenes and being briefly normalized on the High Street—all before the ire of the law closed the fresh mushroom legal loophole. At this twenty-year juncture, it seems an important moment to tell this fascinating tale, and give space for us to reflect upon the tricksy Psilocybe mushroom’s role in recent history.

Find Dr Dickins’ new book ‘Psilocybe Pickers’ here.